As it turns 20, we owe Al Arabiya our thanks … and an apology

https://arab.news/6mpkw

I remember that day, 20 years ago, very well. I had only just started my career as a reporter with the now defunct Future Television in Lebanon, and Al Arabiya was the eagerly awaited media newcomer.

It was two years after the 9/11 attacks, and only a few days before the US-led war in Iraq that would occupy the regional news agenda for years. This was especially true with the coalition’s mismanagement of the “day after” situation, which led to the horrors of Abu Ghraib, the intervention of Iran and the rise of Daesh — leaving Iraq arguably much worse off than it had been under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussain.

More importantly, the birth of the Saudi-backed Al Arabiya came seven years after Qatar launched Al Jazeera. As is well known by now, the latter quickly achieved fame as a controversial 24-hour news network with a cult-like following, no serious competitor and access to the deep pockets of the leadership in Doha.

Much like the reaction to the rise of the internet and social media years later, Al Jazeera was initially welcomed as a beacon of free speech and serious debate, before it quickly revealed its dark side. Indeed, it didn’t take long for the channel, long dominated by Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers, to become known as the mouthpiece for Al Qaeda and the late Osama bin Laden, perpetrators of the September 2001 attacks.

Characterizing its mysterious ties with the world’s most wanted terrorist as a professional relationship and a journalistic scoop, Al Jazeera aired bin Laden tape after bin Laden tape. These broadcasts went unchallenged, uncensored and in perfect harmony with a whole array of programming that incited against the West, non-Muslims and Saudi Arabia — which the channel portrayed as not religious enough and a tool of US foreign policy.

Popular Al Jazeera programs such as “Shariah and Life” (hosted by the late hate preacher Yusuf Al-Qaradawi) and “Open Platform,” along with regular hourly news bulletins, propagated extremist ideas to a staggering 40-plus million Arab viewers a day. When recently asked by a Kuwaiti newspaper about Doha’s ability to rein in such content, former Qatari Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim Al-Thani insisted that Qatar had no control over the network, and that in fact it had caused him numerous headaches during his time in government. This defense might have carried more weight if HBJ were a mere elected official in a small town in Scandinavia, not the second-most powerful man in Qatar.

Against this backdrop, the arrival of the Dubai-based Al Arabiya on March 3, 2003, was more than welcome. It took a few months at the start to find its correct positioning as defined by Sheikh Waleed Al-Ibrahim, the owner of MBC, its parent company and operator. The goal, as he told The New York Times in 2005, was to “position Al Arabiya as the CNN to Al Jazeera's Fox News, as a calm, cool, professional media outlet that would be known for objective reporting rather than for shouted opinions.”

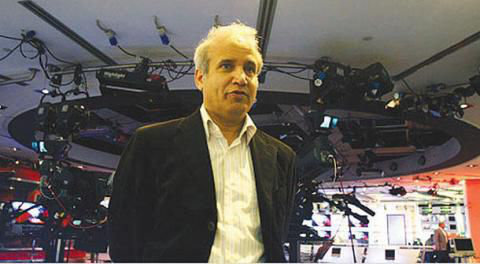

That took a while to achieve, but kicked in at full throttle with the appointment as general manager of Abdulrahman Al-Rashed, the former editor-in-chief of Asharq Al Awsat renowned for his liberal views. This was particularly good news for those of us thirsty for a voice that opposed exploiting religion for political purposes, propagating extremism and insulting the intelligence of Arab viewers.

”...leading a news channel as similar to being on top of a nuclear reactor: You can use it for peaceful purposes or you can weaponize it — Abdulrahman Al-Rashed”

For example, Al Jazeera toed the Al Qaeda line of “expelling infidels from the Arabian peninsula” and incited against Saudi Arabia for hosting the US heroes who helped liberate Kuwait, but failed to criticize its own government — on the same ludicrous grounds — for hosting the largest US military base in the Middle East at Al-Udeid. (By the way, that same base was later used to bomb Iraq, and guess what — Al Jazeera viewers were invited to focus on the US “occupation.”)

Al Arabiya spared no effort and wasted no time. Media historians will credit the channel for its famous “Terrorism has no religion” campaign, and its brave eye-opening programs such as “Death Making,” which dived deep and exposed the evil ideology behind terror groups. It also abolished — at the risk of severe criticism — the practice of labeling suicide attackers as “martyrs.”

Al-Rashed described the job of leading a news channel as similar to being on top of a nuclear reactor: You can use it for peaceful purposes and produce energy, or you can weaponize it.

“People become radicals because extremism is celebrated on TV,” he told The New York Times in 2005. “If you broadcast an extremist message at a mosque, it reaches 50 people. But do you know how many people can be sold by a message on TV?”

Like Plato’s allegory of the cave, many viewers were simply chained to ignorance and refused “to know more”

Faisal J. Abbas

Although Al Arabiya’s efforts went hand in hand with the Saudi government’s security operations to defeat Al Qaeda militarily, it can be argued that the ideological war only truly ended over a decade later with the arrival of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Under Vision 2030, MBS ushered in bold reforms and decisive measures against hate preachers, and made it crystal clear in 2017 that the Kingdom “will not waste 30 more years dealing with any extremist ideas.”

The gap between the physical and ideological battles meant that despite blessing and protection from Riyadh, Al Arabiya’s brave stance against extremism and adherence to professional journalistic standards came at a hefty price. Sadly, many journalists — including the young Iraqi correspondent Atwar Bahjat and her colleagues Adnan Al-Dulaimi and Khalid Al-Fellahi — lost their lives covering the Iraq war. Much like the BBC’s Frank Gardner, another correspondent, Jawad Kazem, was left paralyzed after being shot by militants in Baghdad. Former Al Arabiya South East Asia correspondent (now Arab News Pakistan Bureau Chief) Baker Atyani was kidnapped by Filipino terrorist Abu Sayyaf for 18 months between 2012 and 2013.

While all these incidents came from external factors, what was truly painful was the “friendly fire” from within. For the past two decades Al Arabiya has faced threats and constant smears by radicals, many of them in Saudi Arabia itself, calling it names such as “Al Ebriyah” — the Hebrew, to imply it was serving an Israeli agenda.

I was proud to be Editor-in-Chief of Al Arabiya’s English-language news site from 2012-2016, when I witnessed the consequences of doing the professional thing. There were bomb threats to our headquarters, lawsuits in British courts by UK based lawyers paid to represent evil radical clerics and claim them as freedom fighters, along with personal trolling of my colleagues and our senior management, which over the years has included the (now former) Saudi Media Minister Adel Al-Toraifi, the diplomat Turki Aldakhil, and the current general manager of Asharq News, Nabeel Al-Khatib and Al Arabiya’s current general manager Mamdouh Al-Muhaini.

When the trolls couldn’t find professional grounds, they went personal against news presenters, producers and reporters. Attacks included insults to their gender, religious beliefs and nationalities (despite being Saudi-owned, Al Arabiya prided itself on the international diversity and professionalism of its staff). Such personal attacks were particularly shameful because they came from members of our society blinded by extremist ideologies, and targeted colleagues who — as noted above — risked their lives for the cause of a more enlightened, less violent Arab world.

It is for its dedication to that cause that we — as Saudis, Arabs and Muslims — owe Al Arabiya not only gratitude, but also an apology. Like Plato’s allegory of the cave, many viewers were simply chained to ignorance and refused “to know more” (which is the slogan of the channel). Now that we as a society —thanks to our enlightened, dynamic and decisive leadership — have finally buried our tolerance for intolerance, we need to all get together behind projects like Al Arabiya, and remember that it is only through knowledge that we can progress as society. Here’s to never cursing the messenger, ever again!

• Twitter: @FaisalJAbbas