LONDON: Leaders and scholars from Britain’s Muslim community have told their congregations that there is no conflict between fasting during Ramadan and receiving coronavirus vaccinations.

The month of Ramadan is a holy month for Muslims worldwide, and sees worshippers abstaining from food and drink, between sunrise and sunset.

While religious teachings compel Muslims to refuse “anything entering the body” while fasting, scholars from the UK have said that this rule does not apply to coronavirus vaccines.

Imam Mustafa Hussein, from Birmingham’s Green Lane Masjid mosque, told Arab News: “The vaccine doesn’t have nutritional value, and when we look at injections, we look at what they will provide the body. If the vaccine doesn’t provide the body with any nourishment or nutritional value, then you’re allowed to take it, even if you are fasting.

“It does not break your fast at all. Therefore, there is nothing wrong with taking the vaccine during Ramadan.”

Qari Asim, an imam in Leeds and chair of the Mosques and Imams National Advisory Board, echoed Hussein’s ruling, and said it was an opinion shared by the majority of British imams.

“The majority of Islamic scholars are of the view that taking the vaccine during Ramadan will not invalidate the fast,” Asim told the BBC.

Ramadan is expected to begin early next week when the moon is sighted over Makkah in Saudi Arabia.

The month’s timing coincides with a major drive to provide adults with vaccinations across the UK. There has been concern that inoculations for the UK’s 2.5 million Muslims might slow down during the holiday.

British citizens from Pakistan and Bangladesh were already among the groups worst affected by the pandemic, while misinformation campaigns and myths surrounding vaccines also made them more likely to refuse a jab when offered.

To counter this, British mosques and their imams have played a major role in encouraging congregations to take the vaccine, highlighting its religious permissibility. Some mosques have even opened their doors to the UK’s National Health Service for use as vaccination centers.

New data suggests that these efforts have caused major improvements in vaccine confidence.

Figures from polling company Ipsos MORI suggest a significant increase in ethnic minority Britons who say they have had, or are likely to have, the vaccine — up from 77 percent in January to 92 percent in March.

Kelly Beaver, managing director of Ipsos MORI, said: “It is extraordinarily encouraging to see the steady progress being made with vaccine confidence across the UK. The increase in vaccine confidence among ethnic minority Britons is a particularly welcome sign, given the disproportionate impact that the pandemic has had on ethnic minority communities.”

Vaccines allowed while fasting, UK Muslim leaders say

https://arab.news/6camg

Vaccines allowed while fasting, UK Muslim leaders say

- “The majority of Islamic scholars are of the view that taking the vaccine during Ramadan will not invalidate the fast”: Qari Asim

- Britain’s mosques have played leading role in raising health awareness, fighting fake coronavirus news

France threatens new sanctions against West Bank settlers

- In February, 28 ‘extremist Israeli settlers’ were banned from entering French territory

- At least 488 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli troops or settlers in the West Bank since October 7, according to Palestinian officials

PARIS: France is considering extending sanctions on Israeli settlers behind violence against Palestinian civilians in the occupied West Bank, President Emmanuel Macron’s office said he spoke with Jordan’s King Abdullah II.

The two leaders “firmly condemned recent Israeli announcements about settlements” in the West Bank, “which are contrary to international law,” Macron’s office said in a statement.

Tensions have mounted in the occupied territories since the Hamas October 7 attack on Israel that set off the Gaza war. At least 488 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli troops or settlers in the West Bank since October 7, according to Palestinian officials.

In February, 28 “extremist Israeli settlers” were banned from entering French territory. Last week the European Union imposed sanctions on four Israeli settlers and two settler organizations for violence against Palestinians in the West Bank and Jerusalem.

Since the start of the year, Israeli authorities have declared nearly 1,100 hectares (2,720 acres) of the West Bank to be “state land” — twice as much as in the previous record year in 1999, according to the settlement watchdog Peace Now.

The status gives the government full control over how the land is used, inevitably leading it to being declared off-limits to Palestinians.

Some 490,000 Israeli settlers now live in the West Bank alongside three million Palestinians.

Macron and King Abdullah also spoke about the “catastrophic humanitarian situation in Gaza” and expressed “great concern about the perspective of an Israeli offensive on Rafah, where more than 1.5 million people are seeking refuge, and reiterated their opposition to such an operation,” the statement said.

“The two also insisted on the necessity of an immediate and durable ceasefire to allow massive deliveries of urgent aid and the protection of civilian populations,” it added.

Macron also “repeated that the liberation of hostages held by Hamas was an absolute priority for France.”

Ukraine pulls US-provided Abrams tanks from the front lines over Russian drone threats

- Five of the 31 tanks the US sent to Ukraine in January 2023 have already been lost to Russian drone attacks

- US officials said they will work with the Ukrainians to reset tactics to make the tanks more effective

WASHINGTON: Ukraine has sidelined US-provided Abrams M1A1 battle tanks for now in its fight against Russia, in part because Russian drone warfare has made it too difficult for them to operate without detection or coming under attack, two US military officials told The Associated Press.

The US agreed to send 31 Abrams to Ukraine in January 2023 after an aggressive monthslong campaign by Kyiv arguing that the tanks, which cost about $10 million apiece, were vital to its ability to breach Russian lines.

But the battlefield has changed substantially since then, notably by the ubiquitous use of Russian surveillance drones and hunter-killer drones. Those weapons have made it more difficult for Ukraine to protect the tanks when they are quickly detected and hunted by Russian drones or rounds.

Five of the 31 tanks have already been lost to Russian attacks.

The proliferation of drones on the Ukrainian battlefield means “there isn’t open ground that you can just drive across without fear of detection,” a senior defense official told reporters Thursday.

The official spoke on the condition of anonymity to provide an update on US weapons support for Ukraine before Friday’s Ukraine Defense Contact Group meeting.

For now, the tanks have been moved from the front lines, and the US will work with the Ukrainians to reset tactics, said Joint Chiefs of Staff Vice Chairman Adm. Christopher Grady and a third defense official who confirmed the move on the condition of anonymity.

“When you think about the way the fight has evolved, massed armor in an environment where unmanned aerial systems are ubiquitous can be at risk,” Grady told the AP in an interview this week, adding that tanks are still important.

“Now, there is a way to do it,” he said. “We’ll work with our Ukrainian partners, and other partners on the ground, to help them think through how they might use that, in that kind of changed environment now, where everything is seen immediately.”

News of the sidelined tanks comes as the US marks the two-year anniversary of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, a coalition of about 50 countries that meets monthly to assess Ukraine’s battlefield needs and identify where to find needed ammunition, weapons or maintenance to keep Ukraine’s troops equipped.

Recent aid packages, including the $1 billion military assistance package signed by President Joe Biden on Wednesday, also reflect a wider reset for Ukrainian forces in the evolving fight.

The US is expected to announce Friday that it also will provide about $6 billion in long-term military aid to Ukraine, US officials said, adding that it will include much sought after munitions for Patriot air defense systems. The officials spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss details not yet made public.

The $1 billion package emphasized counter-drone capabilities, including .50-caliber rounds specifically modified to counter drone systems; additional air defenses and ammunition; and a host of alternative, and cheaper, vehicles, including Humvees, Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicles and Mine Resistant Ambush Protected Vehicles.

The US also confirmed for the first time that it is providing long-range ballistic missiles known as ATACMs, which allow Ukraine to strike deep into Russian-occupied areas without having to advance and be further exposed to either drone detection or fortified Russian defenses.

While drones are a significant threat, the Ukrainians also have not adopted tactics that could have made the tanks more effective, one of the US defense officials said.

After announcing it would provide Ukraine the Abrams tanks in January 2023, the US began training Ukrainians at Grafenwoehr Army base in Germany that spring on how to maintain and operate them. They also taught the Ukrainians how to use them in combined arms warfare — where the tanks operate as part of a system of advancing armored forces, coordinating movements with overhead offensive fires, infantry troops and air assets.

As the spring progressed and Ukraine’s highly anticipated counteroffensive stalled, shifting from tank training in Germany to getting Abrams on the battlefield was seen as an imperative to breach fortified Russian lines. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky announced on his Telegram channel in September that the Abrams had arrived in Ukraine.

Since then, however, Ukraine has only employed them in a limited fashion and has not made combined arms warfare part of its operations, the defense official said.

During its recent withdrawal from Avdiivka, a city in eastern Ukraine that was the focus of intense fighting for months, several tanks were lost to Russian attacks, the official said.

A long delay by Congress in passing new funding for Ukraine meant its forces had to ration ammunition, and in some cases they were only able to shoot back once for every five or more times they were targeted by Russian forces.

In Avdiivka, Ukrainian forces were badly outgunned and fighting back against Russian glide bombs and hunter-killer drones with whatever ammunition they had left.

Harvey Weinstein’s rape conviction is overturned by New York’s top court

- The court found the trial judge unfairly allowed testimony against Weinstein based on allegations that weren’t part of the case

- The 72-year-old ex-movie mogul, however, will remain in prison because he was convicted in Los Angeles in 2022 of another rape

NEW YORK: New York’s highest court on Thursday threw out Harvey Weinstein ‘s 2020 rape conviction with a ruling that shocked and disappointed women who celebrated historic gains during the #MeToo era and left those who testified in the case bracing for a retrial against the ex-movie mogul.

The court found the trial judge unfairly allowed testimony against Weinstein based on allegations that weren’t part of the case.

Weinstein, 72, will remain in prison because he was convicted in Los Angeles in 2022 of another rape. But the New York ruling reopens a painful chapter in America’s reckoning with sexual misconduct by powerful figures — an era that began in 2017 with a flood of allegations against Weinstein.

#MeToo advocates noted that Thursday’s ruling was based on legal technicalities and not an exoneration of Weinstein’s behavior, saying the original trial irrevocably moved the cultural needle on attitudes about sexual assault.

The Manhattan district attorney’s office said it intends to retry Weinstein, and at least one of his accusers said through her lawyer that she would testify again.

The state Court of Appeals overturned Weinstein’s 23-year sentence in a 4-3 decision, saying “the trial court erroneously admitted testimony of uncharged, alleged prior sexual acts” and permitted questions about Weinstein’s “bad behavior” if he had testified. It called this “highly prejudicial” and “an abuse of judicial discretion.”

In a stinging dissent, Judge Madeline Singas wrote that the Court of Appeals was continuing a “disturbing trend of overturning juries’ guilty verdicts in cases involving sexual violence.” She said the ruling came at “the expense and safety of women.”

In another dissent, Judge Anthony Cannataro wrote that the decision was “endangering decades of progress in this incredibly complex and nuanced area of law” regarding sex crimes after centuries of “deeply patriarchal and misogynistic legal tradition.”

The reversal of Weinstein’s conviction is the second major #MeToo setback in the last two years. The US Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal of a Pennsylvania court decision to throw out Bill Cosby’s sexual assault conviction.

Weinstein has been in a New York prison since his conviction for forcibly performing oral sex on a TV and film production assistant in 2006, and rape in the third degree for an attack on an aspiring actor in 2013. He was acquitted on the most serious charges — two counts of predatory sexual assault and first-degree rape.

He was sentenced to 16 years in prison in the Los Angeles case.

Weinstein’s lawyers expect Thursday’s ruling to have a major impact on the appeal of his Los Angeles rape conviction. Their arguments are due May 20.

Jennifer Bonjean, a Weinstein attorney, said the California prosecution also relied on evidence of uncharged conduct alleged against him.

“A jury was told in California that he was convicted in another state for rape,” Bonjean said. “Turns out he shouldn’t have been convicted and it wasn’t a fair conviction. … It interfered with his presumption of innocence in a significant way in California.”

Weinstein lawyer Arthur Aidala called the Court of Appeals ruling “a tremendous victory for every criminal defendant in the state of New York.”

Attorney Douglas H. Wigdor, who has represented eight Harvey Weinstein accusers including two witnesses at the New York criminal trial, called it “a major step back” and contrary to routine rulings by judges allowing evidence of uncharged acts to help jurors understand the intent or patterns of a defendant’s criminal behavior.

Debra Katz, a prominent civil rights and #MeToo attorney who represented several Weinstein accusers, said her clients are “feeling gutted” by the ruling, but she believes — and is telling them — that their testimony had changed the world.

“People continue to come forward, people continue to support other victims who’ve reported sexual assault and violence, and I truly believe there’s no going back from that,” Katz said. She predicted Weinstein will be convicted at a retrial and said accusers like her client Dawn Dunning feel great comfort knowing he will remain behind bars.

Dunning, a former actor who was a supporting witness at the New York trial, said in remarks to The Associated Press conveyed through Katz that she was “shocked” by the ruling and dealing with a range of emotions, including asking herself, “Was it all for naught?”

“It took two years of my life,” Dunning said. “I had to live through it every day. But would I do it again? Yes.”

She said that in confronting Weinstein, she faced her worst fear and realized he had no power over her.

Weinstein’s conviction in 2020 was heralded by activists and advocates as a milestone achievement, but dissected just as quickly by his lawyers and, later, the Court of Appeals when it heard arguments on the matter in February.

Allegations against Weinstein, the once powerful and feared studio boss behind such Oscar winners as “Pulp Fiction” and “Shakespeare in Love,” ushered in the #MeToo movement.

Dozens of women came forward to accuse Weinstein, including stars such as Ashley Judd and Uma Thurman. His New York trial drew intense publicity, with protesters chanting “rapist” outside the courthouse.

“This is what it’s like to be a woman in America, living with male entitlement to our bodies,” Judd said Thursday.

Weinstein, incarcerated at the Mohawk Correctional Facility, about 100 miles (160 kilometers) northwest of Albany, maintains his innocence. He contends any sexual activity was consensual.

His lawyers argued on appeal that the trial overseen by Judge James Burke was unfair because testimony was allowed from three women whose claims of unwanted sexual encounters with Weinstein were not part of the charges. Burke’s term expired at the end of 2022, and he is no longer a judge.

They also appealed the judge’s ruling that prosecutors could confront Weinstein over his long history of brutish behavior, including allegations of punching his movie producer brother at a business meeting, snapping at waiters, hiding a woman’s clothes and threatening to cut off a colleague’s genitals with gardening shears.

As a result, Weinstein, who wanted to testify, did not take the stand, Aidala said.

The appeals court labeled the allegations “appalling, shameful, repulsive conduct” but warned that “destroying a defendant’s character under the guise of prosecutorial need” did not justify some trial evidence and testimony.

In a majority opinion written by Judge Jenny Rivera, the Court of Appeals said defendants have a right to be held accountable “only for the crime charged and, thus, allegations of prior bad acts may not be admitted against them for the sole purpose of establishing their propensity for criminality.”

The Court of Appeals agreed last year to take Weinstein’s case after an intermediate appeals court upheld his conviction. Prior to their ruling, judges on the lower appellate court at oral arguments had raised doubts about Burke’s conduct. One observed that Burke let prosecutors pile on with “incredibly prejudicial testimony” from additional witnesses.

At a news conference, Aidala predicted that the lasting effect of the reversal would be that more defendants will testify at their trials, including Weinstein, who “will be able to tell his side of the story.”

He said that when he spoke to Weinstein on Thursday, his client told him: “I’ve been here for years in prison for something I didn’t do. You got to fix this.”

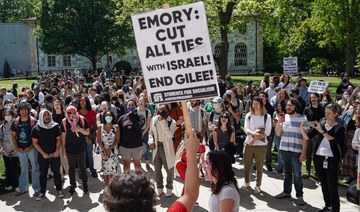

Wave of pro-Palestinian campus protests in US meets forceful response

- Students protesters tasered and teargassed in Atlanta and "swept away" in Austin, Texas

- More than 530 arrests have been made in the last week across major US universities in relation to protests over Gaza

NEW YORK: Fresh clashes between police and students opposed to Israel’s war in Gaza broke out on Thursday, raising questions about forceful methods being used to shut down protests that have intensified since mass arrests at Columbia University last week.

Over the past two days, law enforcement at the behest of college administrators have deployed Tasers and tear gas against students protesters at Atlanta’s Emory University, activists say, while officers clad in riot gear and mounted on horseback have swept away demonstrations at the University of Texas in Austin.

At Columbia, the epicenter of the US protest movement, university officials are locked in a stalemate with students over the removal of a tent encampment set up two weeks ago as a protest against the Israeli offensive.

The administration, which has already allowed an initial deadline for an agreement with students to lapse, has given protesters until Friday to strike a deal.

Other universities appear determined to prevent similar, long-running demonstrations to take root, opting to work with police to shut them down quickly and in some cases, with force.

Overall, more than 530 arrests have been made in the last week across major US universities in relation to protests over Gaza, according to a Reuters tally. University authorities have said the demonstrations are often unauthorized and called on police to clear them.

At Emory, police detained at least 15 people on its Atlanta campus, according to local media, after protesters began erecting a tent encampment in an attempt to emulate a symbol of vigilance employed by protesters at Columbia and elsewhere.

The local chapter of the activist group Jewish Voice for Peace said officers used tear gas and Tasers to dispense the demonstration and take some protesters into custody.

Video footage aired on FOX 5 Atlanta showed a melee breaking out between officers and some protesters, with officers using what appeared to be a stun gun to subdue a person and others wrestling other protesters to the ground and leading them away.

“Several dozen protesters trespassed into Emory University’s campus early Thursday morning and set up tents,” the school wrote in response to an emailed request for comment. It described the protesters as “activists attempting to disrupt our university,” but did not comment directly on the reports of violence.

Atlanta police did not immediately respond to inquiries about the number of protesters who were detained or about reports over the use of tear gas and stun guns.

Similar scenarios unfolded on the New Jersey campus of Princeton University where officers swarmed a newly-formed encampment, video footage on social media showed.

Boston police earlier forcibly removed a pro-Palestinian encampment set up by Emerson College, arresting more than 100 people, media accounts and police said. The latest clashes came a day after police in riot gear and on horseback descended on hundreds of student protesters at the University of Texas at Austin and arrested dozens of them.

But prosecutors on Thursday dropped charges against most of the 60 people taken into custody, mostly on misdemeanor charges of criminal trespassing and disorderly conduct, and said they would proceed with only 14 of those cases.

In dropping the charges, the Travis County district attorney cited “deficiencies in the probable cause affidavits.”

‘Alarming reports’

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union have condemned the arrest of protesters and urged authorities to respect their free speech rights.

But some Republicans in Congress have accused university administrators of allowing Jewish students to be harassed, putting increasing pressure on schools to tightly control any demonstrations and to block any semi-permanent encampment.

US Education Secretary Miguel Cardona on Thursday said his department was closely monitoring the protests, including what he called “very alarming reports of antisemitism.”

In response, activist groups have strongly denied that the protests are antisemitic. Their aim is to pressure universities from divesting from companies that contribute to the Israeli military actions in Gaza, they say.

Even so, protest leaders have acknowledged that hateful rhetoric has been directed at Jewish students, but insist that people who tried to infiltrate and malign their movement are responsible for any harassment.

Friday deadline at Columbia

At Columbia, officials have given protesters until 4 a.m. on Friday to reach an agreement with the university on dismantling dozens of tents set up on the New York City campus in a protest that started a week ago.

An initial deadline of midnight Tuesday came and went without an agreement, but administrators extended it for 48 hours, citing progress in the talks.

The university already tried to shut the protest down by force. On April 18, Columbia President Minouche Shafik took the unusual move of asking police to enter the campus, drawing the ire of many rights groups, students and faculty.

More than 100 people were arrested and the tents were removed from the main lawn. But within a few days, the encampment was back in place, and the university’s options appeared to narrow.

Protesters have vowed to keep the protests going until their universities agree to disclose and divest any financial holdings that might support the war in Gaza, and grant amnesty to students suspended from school during the demonstrations.

Student protesters have also demanded that the US government rein in Israeli strikes on civilians in Gaza, which have killed more than 34,000 people, according to Palestinian health authorities. Israel is retaliating against an Oct. 7 Hamas attack that killed 1,200 people and led to 253 taken hostage, according to Israeli tallies.

Macron blasts ‘ineffective’ UK Rwanda deportation law

PARIS: French President Emmanuel Macron on Thursday said Britain’s plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda was “ineffective” and showed “cynicism” while praising the two countries’ cooperation on defense.

“I don’t believe in the model ... which would involve finding third countries on the African continent or elsewhere where we’d send people who arrive on our soil illegally, who don’t come from these countries,” Macron said.

“We’re creating a geopolitics of cynicism which betrays our values and will build new dependencies, and which will prove completely ineffective,” he added in a wide-ranging speech on the future of the European Union at Paris’ Sorbonne University.

British MPs on Tuesday passed a law providing for undocumented asylum seekers to be sent to Rwanda, where their asylum claims would be processed and where they would stay if the claims succeed.

The law is a flagship policy for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government, which badly lags the opposition Labour Party in the polls, with an election expected within months.

Britain pays Paris to support policing of France’s northern coast, which aims to prevent migrants from setting off for perilous crossings in small boats.

Five people, including one child, were killed in an attempted crossing Tuesday, bringing the toll on the route so far this year to 15 — already higher than the 12 deaths in 2023.

But Macron had warm words for London when he praised the two NATO allies’ bilateral military cooperation, which endured through the contentious years of Britain’s departure from the EU.

“The British are deep natural allies (for France), and the treaties that bind us together ... lay a solid foundation,” he said.

“We have to follow them up and strengthen them because Brexit has not affected this relationship,” Macron added.

The president also said France should seek similar “partnerships” with fellow EU members.