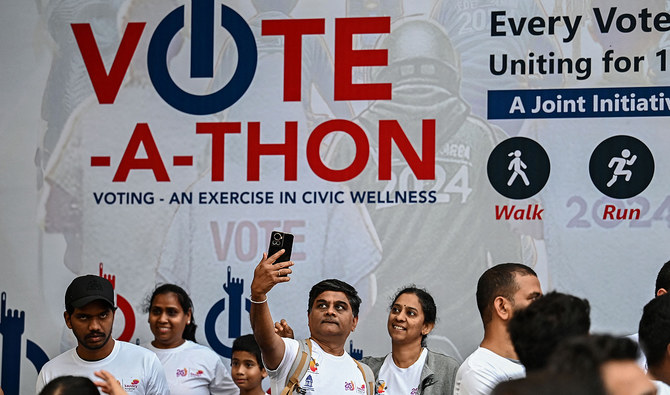

NEW DELHI: India announced Saturday that national polls would begin on April 19, with Hindu-nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi strongly favored to win a third term in the world’s biggest democracy.

Nearly a billion people are eligible to cast ballots in what will be the largest exercise of the democratic franchise in human history, conducted over six weeks.

Many consider Modi’s re-election a foregone conclusion, owing to both the premier’s robust popularity a decade after taking office and a glaringly uneven playing field.

His opponents have been hamstrung by infighting and what critics say are politically motivated legal investigations aimed at hobbling any challengers to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

“We will take democracy to every corner of the country,” chief election commissioner Rajiv Kumar said at a press conference in New Delhi announcing the voting dates.

“It is our promise to deliver a national election in a manner that we... remain a beacon for democracy around the world.”

Voting will be staggered over seven stages between April 19 and June 1.

Ballots from around the country will be counted all at once on June 4 and are usually announced on the same day.

Modi, 73, has already begun unofficial campaigning as he seeks a repeat of his landslide wins of 2014 and 2019, forged in part by his muscular appeals to India’s majority faith.

In January, Modi presided over the inauguration of a grand temple to the deity Ram in the once-sleepy town of Ayodhya, built on the grounds of a centuries-old mosque razed by Hindu zealots.

Construction of the temple fulfilled a long-standing demand of Hindu activists and was widely celebrated across India with back-to-back television coverage and street parties.

The opposition Congress, which led India’s independence struggle and ruled the country almost uninterrupted for decades after its conclusion, is meanwhile a shadow of its former self and out of office in all but three of the country’s 28 states.

Its leaders have sought to stitch together an alliance of more than two dozen regionalist parties to present a united front against the BJP’s well-oiled and well-funded electoral juggernaut.

But the bloc has been plagued by disputes over seat-sharing deals, suffered the defection of one of its members to the government and has so far been unable to publicly agree which of its leaders will be its prime ministerial candidate.

Several party leaders in the alliance are the subject of active investigations or criminal proceedings, and critics have accused Modi’s government of using law enforcement agencies to selectively target its political foes.

Rahul Gandhi — the most prominent Congress politician whose father, grandmother and great-grandfather all served as prime ministers — was briefly disqualified from parliament last year after being convicted of criminal libel.

He faces at least 10 other defamation proceedings in courts around the country, many filed years ago by BJP officials and slowly snaking their way through India’s glacial criminal justice system.

Gandhi, 53, has criticized the government for democratic backsliding and its chest-thumping Hindu nationalism, which have left many of the country’s 210-million-strong Muslim minority fearful for their futures.

He has also called into question Modi’s probity by highlighting his close ties to tycoon industrialist Gautam Adani, whose business empire saw a market meltdown last year after a US short-seller investment firm accused it of corporate fraud.

But Gandhi has already led Congress to two successive humiliating defeats against Modi and there is no sign his efforts to dent the premier’s popularity have registered with the public.

Published opinion polls are rare in India but a Pew survey last year found Modi was viewed favorably by nearly 80 percent of Indians.

A February poll of urban voters conducted by YouGov showed the BJP comfortably leading India’s manifold opposition parties among 47 percent of those surveyed, while Congress was a dismal second at 11 percent.

“Wherever I go, I can clearly see that Modi will become PM for the third time,” Amit Shah, India’s home minister and Modi’s closest political ally, said in a speech this week.

A total of 970 million people are eligible to vote in the election — more than the entire population of the United States, European Union and Russia combined.

There will be more than a million polling stations in operation staffed by 15 million poll workers, according to the election commission.

India to hold marathon national election from April

Short Url

https://arab.news/jmzyt

India to hold marathon national election from April

- Over 970 million people are eligible to vote in India’s election, more than populations of the US, EU and Russia combined

- Many consider Modi’s re-election a foregone conclusion, owing to his popularity and a glaringly uneven playing field

Greenland villagers focus on ‘normal life’ amid stress of US threat

- Proudly showing off photographs on her tablet of her grandson’s first hunt, Dorthe Olsen refuses to let the turmoil sparked by US president Donald Trump take over her life

SARFANNGUIT: Proudly showing off photographs on her tablet of her grandson’s first hunt, Dorthe Olsen refuses to let the turmoil sparked by US president Donald Trump take over her life in a small hamlet nestled deep in a Greenland fjord.

Sarfannguit, founded in 1843, is located 36 kilometers (22 miles) east of El-Sisimiut, Greenland’s second-biggest town, and is accessible by boat in summer and snowmobile or dogsled in winter if the ice freezes.

The settlement has just under 100 residents, most of whom live off from hunting and fishing.

On this February day, only the wind broke the deafening silence, whipping across the scattering of small colorful houses.

Most of them looked empty. At the end of a gravel road, a few children played outdoors, rosy-cheeked in the bitter cold, one wearing a Spiderman woolly hat.

“Everything is very calm here in Sarfannguit,” said Olsen, a 49-year-old teacher, welcoming AFP into her home for coffee and traditional homemade pastries and cakes.

In the background, a giant flat screen showed a football match from England’s Premier League.

Olsen told AFP of the tears of pride she shed when her grandson killed his first caribou at age 11, preferring to talk about her family than about Trump.

The US president has repeatedly threatened to seize the mineral-rich island, an autonomous territory of Denmark, alleging that Copenhagen is not doing enough to protect it from Russia and China.

He nevertheless climbed down last month and agreed to negotiations.

Greenland’s health and disability minister, Anna Wangenheim, recently advised Greenlanders to spend time with their families and focus on their traditions, as a means of coping with the psychological stress caused by Trump’s persistent threats.

The US leader’s rhetoric “has impacted a lot of people’s emotions during many weeks,” Wangenheim told AFP in Nuuk.

’Powerless’

Olsen insisted that the geopolitical crisis — pitting NATO allies against each other in what is the military alliance’s deepest crisis in years — “doesn’t really matter.”

“I know that Greenlanders can survive this,” she said.

Is she not worried about what would happen to her and her neighbors if the worst were to happen — a US invasion — especially given her settlement’s remote location?

“Of course I worry about those who live in the settlements,” she said.

“If there’s going to be a war and you are on a settlement, of course you feel powerless about that.”

The only thing to do is go on living as normally as possible, she said, displaying Greenland’s spirit of resilience.

That’s the message she tries to give her students, who get most of their news from TikTok.

“We tell them to just live the normal life that we live in the settlement and tell them it’s important to do that.”

The door opened. It was her husband returning from the day’s hunt, a large plastic bag in hand containing a skinned seal.

Olsen cut the liver into small pieces, offering it with bloodstained fingers to friends and family gathered around the table.

“It’s my granddaughter’s favorite part,” she explained.

Fishing and hunting account for more than 90 percent of Greenland’s exports.

No private property

Back in El-Sisimiut after a day out seal hunting on his boat, accompanied by AFP, Karl-Jorgen Enoksen stressed the importance of nature and his profession in Greenland.

He still can’t get over the fact that an ally like the United States could become so hostile toward his country.

“It’s worrying and I can’t believe it’s happening. We’re just trying to live the way we always have,” the 47-year-old said.

The notion of private property is alien to Inuit culture, characterised by communal sharing and a deep connection to the land.

“In Greenlandic tradition, our hunting places aren’t owned. And when there are other hunters on the land we are hunting on, they can just join the hunt,” he explained.

“If the US ever bought us, I can for example imagine that our hunting places would be bought.”

“I simply just can’t imagine that,” he said, recalling that his livelihood is already threatened by climate change.

He doesn’t want to see his children “inherit a bad nature — nature that we have loved being in — if they are going to buy us.”

“That’s why it is we who are supposed to take care of OUR land.”

Sarfannguit, founded in 1843, is located 36 kilometers (22 miles) east of El-Sisimiut, Greenland’s second-biggest town, and is accessible by boat in summer and snowmobile or dogsled in winter if the ice freezes.

The settlement has just under 100 residents, most of whom live off from hunting and fishing.

On this February day, only the wind broke the deafening silence, whipping across the scattering of small colorful houses.

Most of them looked empty. At the end of a gravel road, a few children played outdoors, rosy-cheeked in the bitter cold, one wearing a Spiderman woolly hat.

“Everything is very calm here in Sarfannguit,” said Olsen, a 49-year-old teacher, welcoming AFP into her home for coffee and traditional homemade pastries and cakes.

In the background, a giant flat screen showed a football match from England’s Premier League.

Olsen told AFP of the tears of pride she shed when her grandson killed his first caribou at age 11, preferring to talk about her family than about Trump.

The US president has repeatedly threatened to seize the mineral-rich island, an autonomous territory of Denmark, alleging that Copenhagen is not doing enough to protect it from Russia and China.

He nevertheless climbed down last month and agreed to negotiations.

Greenland’s health and disability minister, Anna Wangenheim, recently advised Greenlanders to spend time with their families and focus on their traditions, as a means of coping with the psychological stress caused by Trump’s persistent threats.

The US leader’s rhetoric “has impacted a lot of people’s emotions during many weeks,” Wangenheim told AFP in Nuuk.

’Powerless’

Olsen insisted that the geopolitical crisis — pitting NATO allies against each other in what is the military alliance’s deepest crisis in years — “doesn’t really matter.”

“I know that Greenlanders can survive this,” she said.

Is she not worried about what would happen to her and her neighbors if the worst were to happen — a US invasion — especially given her settlement’s remote location?

“Of course I worry about those who live in the settlements,” she said.

“If there’s going to be a war and you are on a settlement, of course you feel powerless about that.”

The only thing to do is go on living as normally as possible, she said, displaying Greenland’s spirit of resilience.

That’s the message she tries to give her students, who get most of their news from TikTok.

“We tell them to just live the normal life that we live in the settlement and tell them it’s important to do that.”

The door opened. It was her husband returning from the day’s hunt, a large plastic bag in hand containing a skinned seal.

Olsen cut the liver into small pieces, offering it with bloodstained fingers to friends and family gathered around the table.

“It’s my granddaughter’s favorite part,” she explained.

Fishing and hunting account for more than 90 percent of Greenland’s exports.

No private property

Back in El-Sisimiut after a day out seal hunting on his boat, accompanied by AFP, Karl-Jorgen Enoksen stressed the importance of nature and his profession in Greenland.

He still can’t get over the fact that an ally like the United States could become so hostile toward his country.

“It’s worrying and I can’t believe it’s happening. We’re just trying to live the way we always have,” the 47-year-old said.

The notion of private property is alien to Inuit culture, characterised by communal sharing and a deep connection to the land.

“In Greenlandic tradition, our hunting places aren’t owned. And when there are other hunters on the land we are hunting on, they can just join the hunt,” he explained.

“If the US ever bought us, I can for example imagine that our hunting places would be bought.”

“I simply just can’t imagine that,” he said, recalling that his livelihood is already threatened by climate change.

He doesn’t want to see his children “inherit a bad nature — nature that we have loved being in — if they are going to buy us.”

“That’s why it is we who are supposed to take care of OUR land.”

© 2026 SAUDI RESEARCH & PUBLISHING COMPANY, All Rights Reserved And subject to Terms of Use Agreement.