Hengameh Golestan

‘Untitled (1979)’

This image comes from the self-taught photographer’s “Witness ’79” series, which documented a demonstration by more than 100,000 women on the streets of Tehran protesting the recently issued post-revolution ruling that women had to wear the hijab. “The mood was one of anticipation and excitement, and a bit of fear,” she has said of the protest. “We were actively taking part in shaping our future through actions rather than words and that felt amazing.” Even though Golestan developed the film at the time, the photos were not printed until 2015.

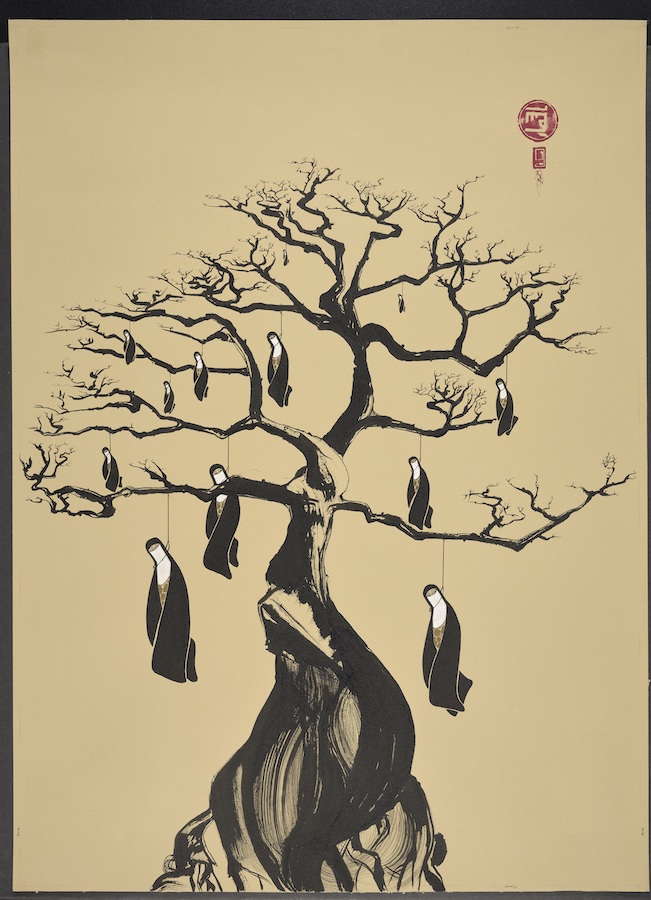

Hayv Kahraman

‘Honor Killing’

The Kurdish-American artist — who fled Iraq with her mother and sister at the end of the First Gulf War — incorporates international influences into her work, from European renaissance art to Japanese woodblock prints via Middle Eastern techniques. “Through her distinct vocabulary she evokes her home in Baghdad, exile and war, and wider issues affecting women,” the museum notes state. In 2017, Kahraman told Glass Magazine: “I am concerned with the multitude, not the self. This is not only my story.” This 2006 work — containing hints of calligraphy — in which women wearing the hijab hand from a tree, “tackles a subject that continues to affect women … across the world,” the museum says. “It refers to the killing of a woman because she is considered to have dishonored the family by transgressing social conventions governing gender relations.”

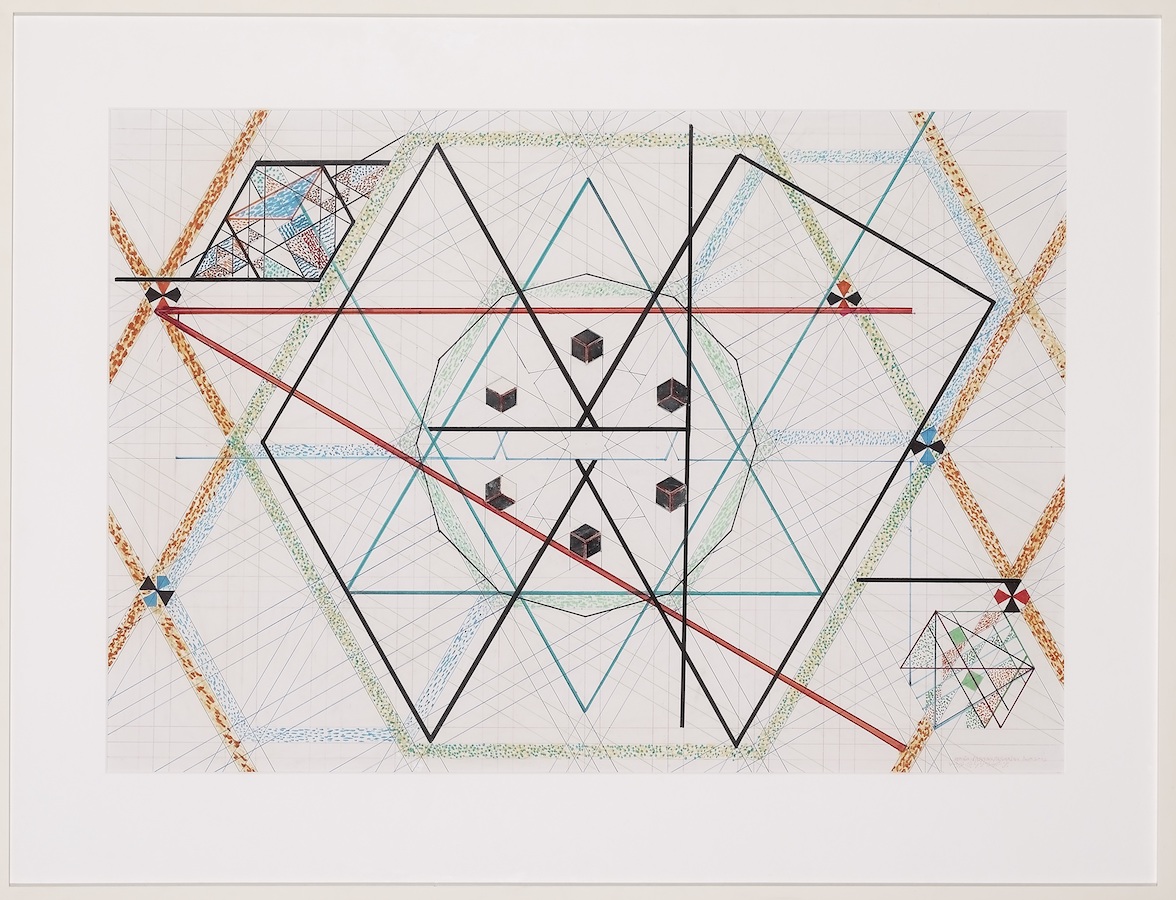

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

‘Untitled (2005)’

Farmanfarmaian became internationally famous for her minimalist, geometrical works (Andy Warhol, with whom she became friends while studying at Parsons School of Design in New York, reportedly kept one of her famed mirror balls on his desk), and though she is best known for her mirrored sculptures, she also produced minimalist, abstract drawings such as this one, in which, the museum notes state, “the central dodecagon is punctuated by cubes of mirror, with multiple triangular grid patterns emanating from the central point.”

Khalil Joreije and Joanna Hadjithomas

‘Faces’

Much of the Lebanese multimedia artists’ work focuses on the 15-year Civil War, the aftereffects of which continue to shape their homeland. The project from which this 2009 work is taken focuses on the victims of that violence — the ‘martyrs’ whose framed images adorn the streets. Traveling throughout Lebanon, the museum says, “they sought out posters of ‘martyrs from all confessions and political backgrounds,’ particularly choosing those that had been left in place for a long time and that had deteriorated, with the features gradually disappearing so that ‘all that remains is an outline of the face, a sketched and mostly unrecognizable shadow. … They intervened in the image, enhancing the shape of an eye or a mouth with graphite as though reclaiming the figures from the shadows of disappearance.”

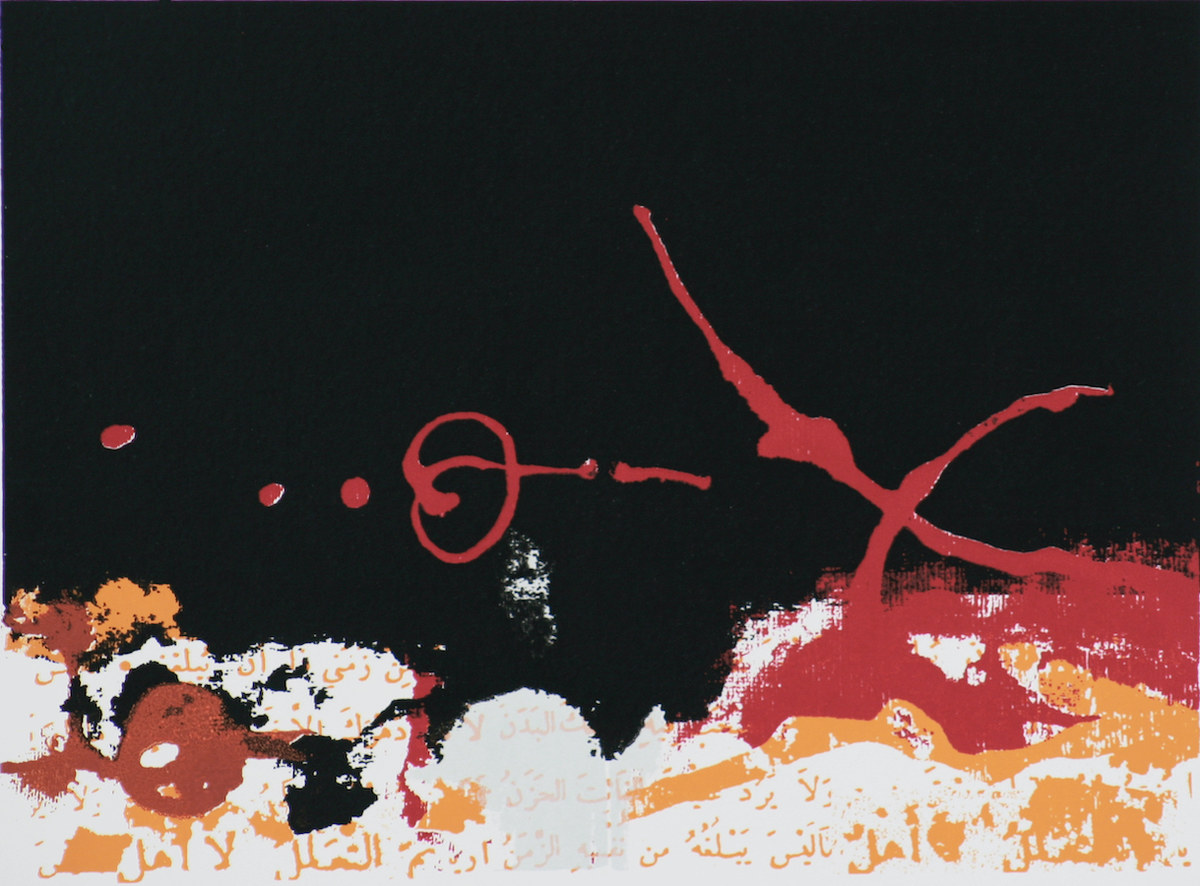

Rafa Nasiri

‘A Library Set On Fire’

The influential Iraqi artist made this 2008 silkscreen — one of a series of six — to mark the burning of Iraq’s National Library, one of the many losses to afflict his homeland in the Iraq War of 2003. Each of the silkscreens includes an extract from Al-Mutanabbi’s poem “On Hearing in Egypt that his Death had been Reported to Saif Al-Dawla in Aleppo.” This one contains the lines: “Unhappy I, friendless, homeless/Solitary, cheerless, comfortless.” The words are, the museum says, “placed within a dark abstract composition, the colours echoing the orange and red flames of a fire.” The notes continue: “As the Iraqi writer May Muzaffar has commented, ‘The burning of books and manuscripts is paralleled with the burning of the mystic al-Hallaj, a human body, and announces not only the death of the book as a social thing/being but also the end of civilization and humanity.’”

Sulafa Hijazi

‘Untitled (2012)’

The Syrian artist began his “Ongoing” series — of which this image is part — in 2011, originally publishing the pieces on social media, which, as the museum notes, “became an increasingly significant platform through which artists in Syria were able to share their work.” In Malu Halasa’s 2012 work “Culture in Defiance: Continuing Traditions of Satire, Art and the Struggle for Freedom in Syria,” she quotes Hijazi as saying: “Before I left the country in 2012, people were still trying to do something positive. We had great hopes about the prospect of changing our country through peaceful means. There was still a space in our society for us to do this. Then it started to become violent; … (now) the sound of weapons drowns out the voices of peaceful activism.”

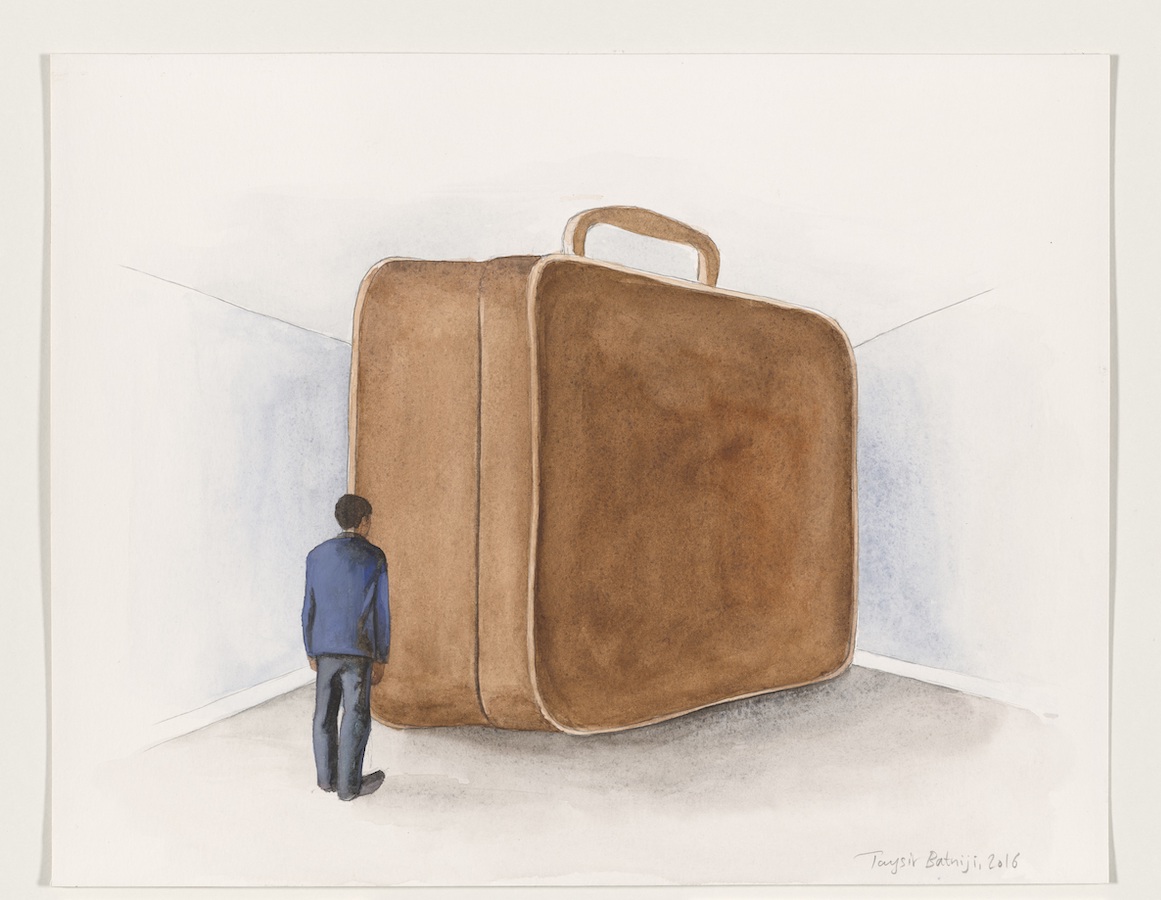

Taysir Batniji

‘Untitled (2016)’

Movement and exile are predominant themes in Batniji’s work, and the suitcase is a recurring symbol of them. “In this watercolor, the suited male figure, dwarfed by the sheer size of the suitcase, can be considered as an insertion of the artist himself,” the museum notes say, adding that the Palestinian artist’s work explores “the notion of being between worlds — in his case the world he lives in, France, and his home, Gaza, which he has not been able to visit since 2012.”