RIYADH: If geography is destiny, then all small countries with much bigger neighbors perforce have to learn to capitalize on the advantages while handling the challenges with tact and finesse.

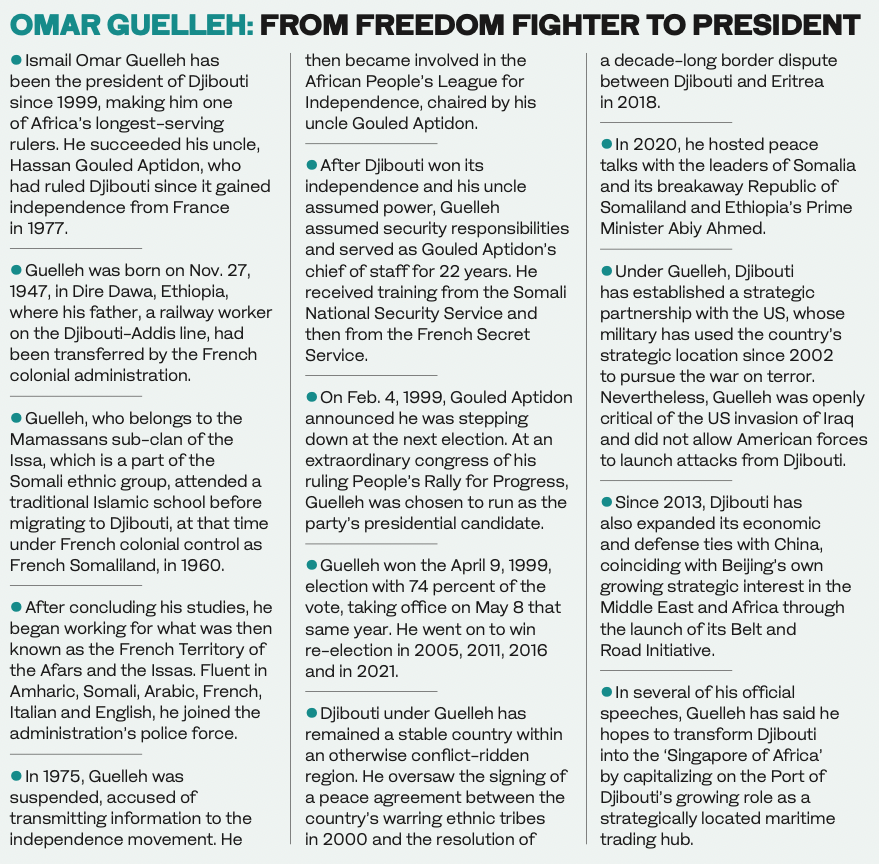

Few countries come close to Djibouti, a tiny African nation squeezed between Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia, in pulling off this feat.

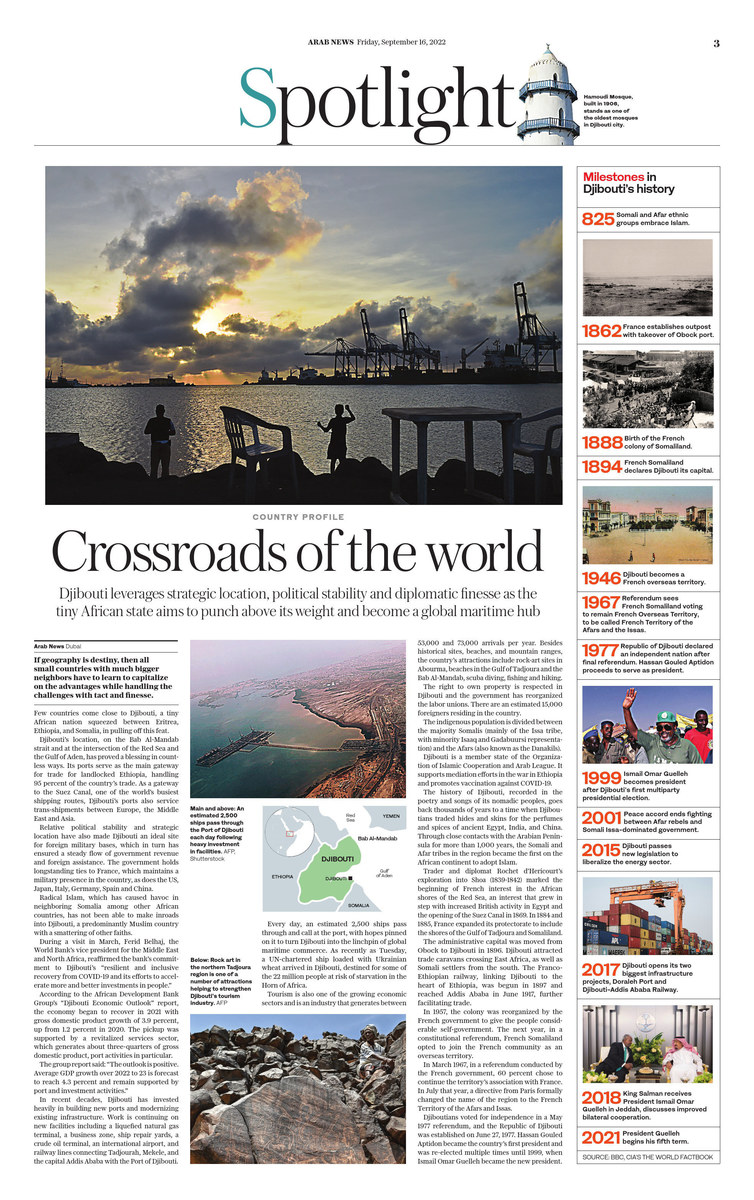

Djibouti’s location, on the Bab Al-Mandab strait and at the intersection of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, has proved a blessing in countless ways. Its ports serve as the main gateway for trade for landlocked Ethiopia, handling 95 percent of the country’s trade. As a gateway to the Suez Canal, one of the world’s busiest shipping routes, Djibouti’s ports also service trans-shipments between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

Relative political stability and strategic location have also made Djibouti an ideal site for foreign military bases, which in turn has ensured a steady flow of government revenue and foreign assistance. The government holds longstanding ties to France, which maintains a military presence in the country, as does the US, Japan, Italy, Germany, Spain, and China.

Tourism is also one of the growing economic sectors of Djibouti and is an industry that generates between 53,000 and 73,000 arrivals per year. (Shutterstock)

Radical Islam, which has caused havoc in neighboring Somalia among other African countries, has not been able to make inroads into Djibouti, a predominantly Muslim country with a smattering of other faiths.

During a visit in March, Ferid Belhaj, the World Bank’s vice president for the Middle East and North Africa, reaffirmed the bank’s commitment to Djibouti’s “resilient and inclusive recovery from COVID-19 and its efforts to accelerate more and better investments in people.”

INTERVIEW

According to the African Development Bank Group’s “Djibouti Economic Outlook” report, the economy began to recover in 2021 with gross domestic product growth of 3.9 percent, up from 1.2 percent in 2020. The pickup was supported by a revitalized services sector, which generates about three-fourths of GDP, port activities in particular.

Djibouti’s ports also service trans-shipments between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. (AFP)

The group report said: “The outlook is positive. Average GDP growth over 2022 to 23 is forecast to reach 4.3 percent and remain supported by port and investment activities.”

In recent decades, Djibouti has invested heavily in building new ports and modernizing existing infrastructure. Work is ongoing on new facilities including a liquefied natural gas terminal, a business zone, ship repair yards, a crude oil terminal, an international airport, and railway lines connecting Tadjourah, Mekele, and the capital Addis Ababa with the Port of Djibouti.

Every day, an estimated 2,500 ships pass through and call through the port, with hopes pinned on it to turn Djibouti into the linchpin of global maritime commerce. As recently as Tuesday, a UN-chartered ship loaded with thousands of tons of Ukrainian wheat arrived in Djibouti, destined for some of the 22 million people at risk of starvation in the Horn of Africa.

Tourism is also one of the growing economic sectors of Djibouti and is an industry that generates between 53,000 and 73,000 arrivals per year. Besides historical sites, a national park, beaches, and mountain ranges, the country’s attractions include rock-art sites in Abourma, islands and beaches in the Gulf of Tadjoura and the Bab Al-Mandab, scuba diving, fishing, trekking, and hiking.

The right to own property is respected in Djibouti and the government has reorganized the labor unions. There are an estimated 15,000 foreigners residing in the country.

The right to own property is respected in Djibouti and the government has reorganized the labor unions. There are an estimated 15,000 foreigners residing in the country.

The indigenous population is divided between the majority Somalis (predominantly of the Issa tribe, with minority Isaaq and Gadabuursi representation) and the Afars (also known as the Danakils).

Djibouti is a member state of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and Arab League. It strongly supports mediation efforts in the war in Ethiopia and promotes vaccination against COVID-19.

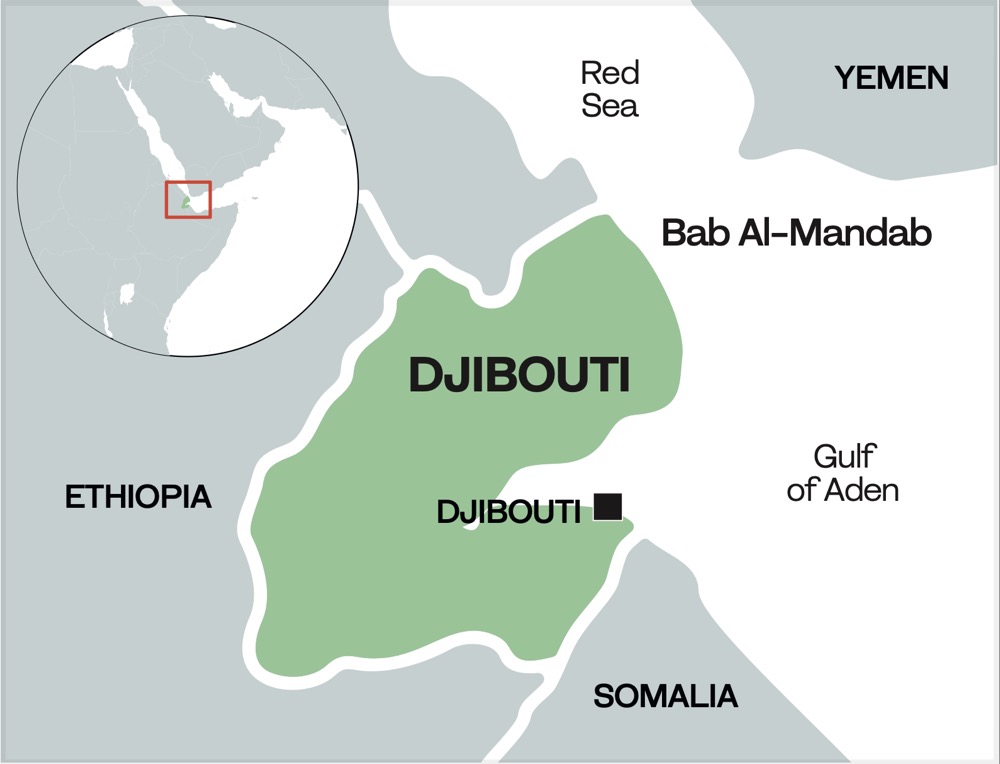

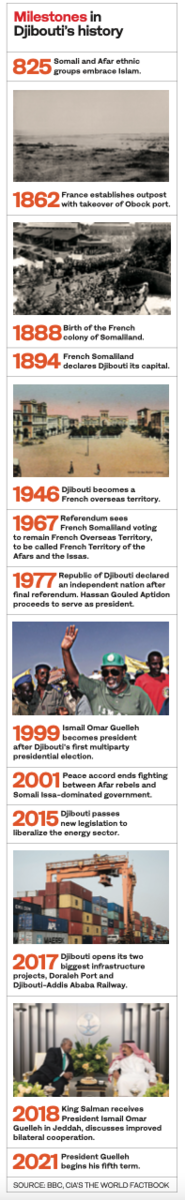

The history of Djibouti, recorded in the poetry and songs of its nomadic peoples, goes back thousands of years to a time when Djiboutians traded hides and skins for the perfumes and spices of ancient Egypt, India, and China. Through close contacts with the Arabian Peninsula for more than 1,000 years, the Somali and Afar tribes in the region became the first on the African continent to adopt Islam.

Trader and diplomat Rochet d’Hericourt’s exploration into Shoa (1839 to 1842) marked the beginning of French interest in the African shores of the Red Sea, an interest that grew in step with increased British activity in Egypt and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. In 1884 and 1885, France expanded its protectorate to include the shores of the Gulf of Tadjoura and Somaliland.

The administrative capital was moved from Obock to Djibouti in 1896. Djibouti attracted trade caravans crossing East Africa, as well as Somali settlers from the south. The Franco-Ethiopian railway, linking Djibouti to the heart of Ethiopia, was begun in 1897 and reached Addis Ababa in June 1917, further facilitating the increase of trade.

Diplomat Rochet d’Hericourt’s exploration into Shoa (1839 to 1842) marked the beginning of French interest in the African shores of the Red Sea. (AFP)

In 1957, the colony was reorganized by the French government to give the people considerable self-government. The next year, in a constitutional referendum, French Somaliland opted to join the French community as an overseas territory.

In March 1967, in a referendum conducted by the French government, 60 percent chose to continue the territory’s association with France. In July of that year, a directive from Paris formally changed the name of the region to the French Territory of the Afars and Issas.

Djiboutians voted for independence in a May 1977 referendum, and the Republic of Djibouti was established on June 27, 1977. Hassan Gouled Aptidon became the country’s first president and was re-elected multiple times until 1999, when Ismail Omar Guelleh became the new president.