CAIRO, Egypt: The doors of jihad opened for Ayman Al-Zawahiri as a young doctor in a Cairo clinic, when a visitor arrived with a tempting offer: a chance to treat Islamic fighters battling Soviet forces in Afghanistan.

With that offer in 1980, Al-Zawahiri embarked on a life that over three decades took him to the top of the most feared terrorist group in the world, Al-Qaeda, after the death of Osama bin Laden.

Already an experienced militant who had sought the overthrow of Egypt’s “infidel” regime since the age of 15, Al-Zawahiri took a trip to the Afghan war zone that was just a few weeks long, but it opened his eyes to new possibilities.

What he saw was “the training course preparing Muslim mujahedeen youth to launch their upcoming battle with the great power that would rule the world: America,” he wrote in a 2001 biography-cum-manifesto.

Al-Zawahiri, 71, was killed over the weekend by a US drone strike in Afghanistan. President Joe Biden announced the death Monday evening in an address to the nation.

The strike is likely to lead to greater disarray within the organization than did bin Laden’s death in 2011, since it is far less clear who his successor would be.

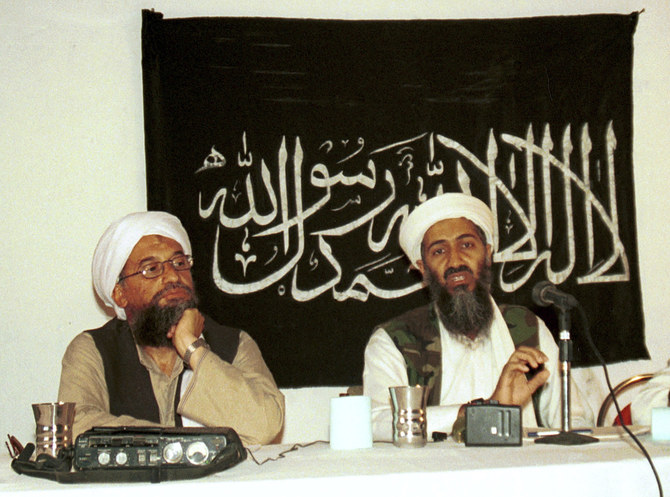

Al-Zawahiri became crucial to turning the jihadi movement’s guns to target the United States as the right-hand man to bin Laden, the young Saudi millionaire he met in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region. Under their leadership, the Al-Qaeda terror network carried out the deadliest attack ever on American soil, the Sept. 11, 2001, suicide hijackings.

The attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon made bin Laden America’s Enemy No. 1. But he likely could never have carried it out without his deputy.

ALSO READ: How potent a threat is Al-Qaeda since Bin Laden’s death?

While bin Laden came from a privileged background in a prominent Saudi family, Al-Zawahiri had the experience of an underground revolutionary. Bin Laden provided Al-Qaeda with charisma and money, but Al-Zawahiri brought tactics and organizational skills needed to forge militants into a network of cells in countries around the world.

“Bin Laden always looked up to him,” said terrorism expert Bruce Hoffman of Georgetown University. Al-Zawahiri “spent time in an Egyptian prison, he was tortured. He was a jihadi from the time he was a teenager.”

When the 2001 US invasion of Afghanistan demolished Al-Qaeda’s safe haven and scattered, killed and captured its members, Al-Zawahiri ensured Al-Qaeda’s survival. He rebuilt its leadership in the Afghan-Pakistan border region and installed allies as lieutenants in key positions.

He also became the movement’s public face, putting out a constant stream of video messages while bin Laden largely hid.

With his thick beard, heavy-rimmed glasses and the prominent bruise on his forehead from prostration in prayer, he was notoriously prickly and pedantic. He picked ideological fights with critics within the jihadi camp, wagging his finger scoldingly in his videos. Even some key figures in Al-Qaeda’s central leadership were put off, calling him overly controlling, secretive and divisive — a contrast to bin Laden, whose soft-spoken presence many militants described in adoring, almost spiritual terms.

Yet he reshaped the organization from a centralized planner of terror attacks into the head of a franchise chain. He led the creation of a network of autonomous branches around the region, including in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, North Africa, Somalia and Asia.

In the decade after 9/11, Al-Qaeda inspired or had a direct hand in attacks in all those areas as well as Europe, Pakistan and Turkey, including the 2004 train bombings in Madrid and the 2005 transit bombings in London. More recently, the Al-Qaeda affiliate in Yemen has proven itself capable of plotting attacks on US soil with an attempted 2009 bombing of an American passenger jet and an attempted package bomb the following year.

Bin Laden was killed in a US raid on his compound in May 2011 in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Less than two months later, Al-Qaeda proclaimed Al-Zawahiri its paramount leader.

The jihad against America “does not halt with the death of a commander or leader,” he said three months after bin Laden’s death. “Chase America, which killed the leader of the mujahedeen and threw his body into the sea.”

The 2011 Arab Spring uprisings around the Mideast threatened a major blow to Al-Qaeda, showing that jihad was not the only way to get rid of Arab autocrats. It was mainly pro-democracy liberals and leftists who led the uprising that toppled Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak, the longtime goal Al-Zawahiri failed to achieve.

But Al-Zawahiri sought to co-opt the wave of uprisings, insisting that they would have been impossible if the 9/11 attacks had not weakened America. And he urged Islamic hard-liners to take over in the nations where leaders had fallen.

Al-Zawahiri was born June 19, 1951, the son of an upper-middle-class family of doctors and scholars in the Cairo suburb of Maadi. His father was a pharmacology professor at Cairo University’s medical school and his grandfather, Rabia Al-Zawahiri, was the grand imam of Al-Azhar University, a premier center of religious study.

From an early age, Al-Zawahiri was enflamed by the radical writings of Sayed Qutb, the Egyptian Islamist who taught that Arab regimes were “infidel” and should be replaced by Islamic rule.

In the 1970s, as he earned his medical degree as a surgeon, he was active in militant circles. He merged his own militant cell with others to form the group Islamic Jihad and began trying to infiltrate the military — at one point even storing weapons in his private clinic.

Then came the 1981 assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat by Islamic Jihad militants. The slaying was carried out by a different cell in the group — and Al-Zawahiri has written that he learned of the plot only hours before the assassination. But he was arrested along with hundreds of other militants and served three years in prison.

During his imprisonment, he was reportedly tortured heavily, a factor some cite as turning him more violently radical.

After his release in 1984, Al-Zawahiri returned to Afghanistan and joined the Arab militants from across the Middle East fighting alongside the Afghans against the Soviets. He courted bin Laden, who became a heroic figure for his financial support of the mujahedeen.

Al-Zawahiri followed bin Laden to his new base in Sudan, and from there he led a reassembled the Islamic Jihad group in a violent campaign of bombings aimed at toppling Egypt’s US-allied government.

In the most daring attack, Jihad and other militants tried to assassinate Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak during a 1995 visit to Ethiopia. Mubarak escaped the hail of gunfire aimed at his motorcade, and his security forces all but crushed the militant movement in Egypt in the crackdown that followed.

The Egyptian movement failed. But Al-Zawahiri would bring to Al-Qaeda the tactics that he honed in Islamic Jihad.

He promoted the use of suicide bombings, to become Al-Qaeda’s hallmark. He plotted a 1995 suicide car bombing of Egypt’s embassy in Islamabad that killed 16 people — presaging the more devastating 1998 Al-Qaeda bombings of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that killed more than 200, attacks Al-Zawahiri was indicted for in the United States.

In 1996, Sudan expelled bin Laden, who took his fighters back to Afghanistan, where they found a safe haven under the radical Taliban regime. Once more, Al-Zawahiri followed.

Two years later, their bond was sealed when bin Laden, Al-Zawahiri and other militant leaders issued the “Declaration of Jihad against Jews and Crusaders.” It announced that the United States was Islam’s top enemy and instructed Muslims that it was their religious duty to “kill the Americans and their allies.”

It consecrated a dramatic shift that Al-Zawahiri underwent under bin Laden’s influence, changing from his longtime strategy of attacking the “near enemy” — US-allied Arab regimes like Egypt — to target the “far enemy,” the United States itself.

Some in Al-Zawahiri’s Islamic Jihad broke away, opposed to the move. And some Al-Qaeda militants whose association with bin Laden predated Al-Zawahiri’s always saw him as an arrogant intruder.

“I have never taken orders from Al-Zawahiri,” Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, one of the network’s top figures in East Africa until his 2011 death, sneered in a memoir posted on line in 2009. “We don’t take orders from anyone but our historical leadership.”

Soon after the alliance came the bombings of the US embassies in Africa, followed by the 2000 suicide bombing of the USS Cole off Yemen, an attack Al-Zawahiri is believed to have helped organize.

When the US invaded Afghanistan, Al-Zawahiri and bin Laden fled into Pakistan as a US airstrike killed Al-Zawahiri’s wife and at least two of their six children in the southern Afghan city of Kandahar.

The CIA came tantalizingly close to possibly capturing Al-Zawahiri in 2003 and killing him in 2004. The CIA thought it finally had Al-Zawahiri in its sights in 2009, only to be tricked by a double agent who blew himself up, killing seven agency employees and wounding six more in Khost, Afghanistan.

In his 2001 treatise, “Knights Under the Prophet’s Banner,” Al-Zawahiri set the long-term strategy for the jihadi movement — to inflict “as many casualties as possible” on the Americans, while trying to establish control in a nation as a base “to launch the battle to restore the holy caliphate” of Islamic rule across the Muslim world.

Al-Qaeda did make inroads in Europe. The bombers in the Madrid attacks that killed 191 were said to have been inspired by Al-Qaeda, although direct links remain uncertain. Al-Zawahiri claimed Al-Qaeda responsibility for the 2005 London transit bombings that killed 52, saying some perpetrators trained in Al-Qaeda camps.

Not all terror campaigns were successful. Al-Qaeda’s branch in Saudi Arabia was crushed by 2006. Al-Zawahiri himself had to write to the head of Al-Qaeda’s branch in Iraq, Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, to rein in his brutal attacks on Iraqi Shiites, which were hurting the network’s image among Muslims.

That underlined Al-Zawahiri’s ultimate failure. With his concentration on a “Muslim vanguard” carrying out dramatic attacks, he never gained widespread popular support for Al-Qaeda in the Islamic world beyond a fringe of radical sympathizers.

His answer, in “Knights Under the Prophet’s Banner,” was for jihadis to continue hitting Americans, hoping to exploit anti-US sentiment and draw in the public. He echoed that strategy in a June 2011 video eulogy to his slain boss.

Bin Laden “terrified America in his life,” he said, and “will continue to terrify it after his death.”