MANILA: Philippines president-elect Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has said he will continue vlogging when he takes office later this month, giving a glimpse into the incoming leader’s public communications strategy after being “inaccessible” to the media during his campaign.

Marcos, the son and namesake of the late dictator, will take over from President Rodrigo Duterte as the country’s leader for the next six years on June 30. He won more than 31 million votes in one of the most divisive presidential elections in the history of the Philippines.

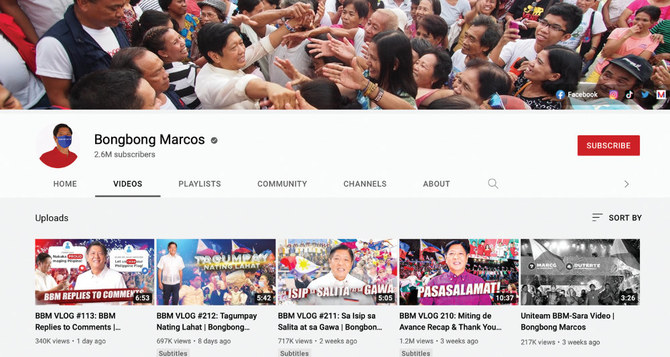

Social media played a huge role throughout his presidential campaign, during which he used vlogs to discuss issues and address supporters. Marcos has more than 7.4 million followers on Facebook and 2.6 million subscribers on YouTube.

In his latest vlog, in which he replied to comments from social media users, Marcos said that he plans to continue vlogging even when he assumes the presidency.

“I need to explain what we are doing, to let you know what you think we need to do right, and to hear your comments on the shortcomings that we need to address,” Marcos said in the video published on Saturday.

“That’s why we will continue this vlog. Every so often, we will explain the things that we are doing so that you don’t just get your news from newspapers, but also straight from the horse’s mouth.”

His latest statement has sparked some concern, as during the campaign period Marcos was seen as difficult to approach by the media.

“He was basically, generally speaking, inaccessible to the media,” Danilo Arao, press freedom advocate and journalism professor at the University of the Philippines, told Arab News.

“The problem right now, though he has not yet been formally assumed as president, he’s already being selective in terms of whom he wants to talk to. Of course, we would hope that the incoming administration would be more open to criticism from the media.”

Since the government has its own public information system to reach out to the public, including on television and online, Arao said that instead of vlogging, Marcos’ administration should maximize existing resources in order to “ensure that the messaging will be more consistent.”

Rights group Human Rights Watch last month highlighted Marcos’ “rocky relationship” with the press, which they said “could pose serious risks for democracy in the Philippines.”

HRW said in a statement: “Ignoring critical publications is bad enough, but Marcos Jr. will have tools at his disposal to muzzle the media in a manner that the elder Marcos, no supporter of press freedom, could only dream of.”