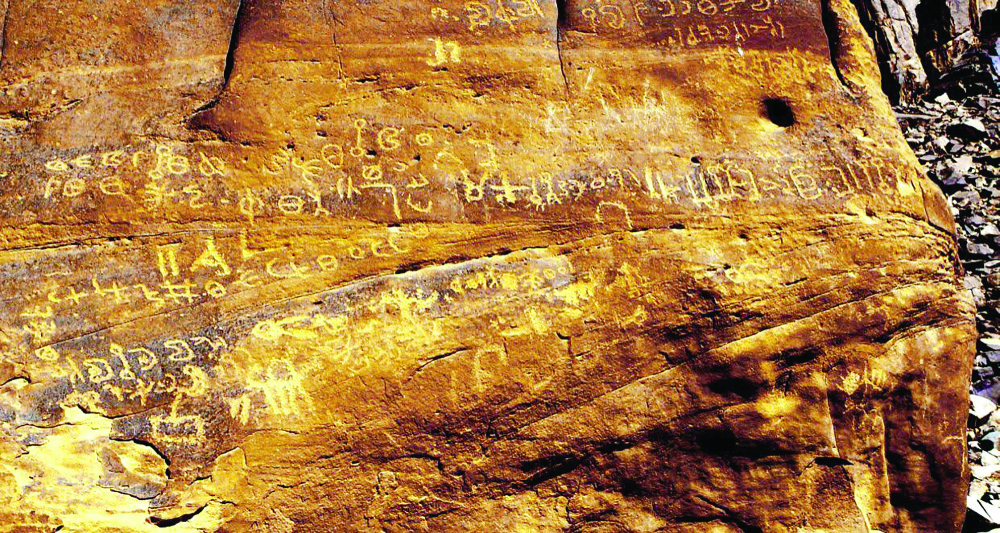

MAKKAH: Ancient inscriptions on rocks throughout the Arabian Peninsula are helping to paint a picture of the earliest Arabic cultures, including economic and social conditions — and even people’s thoughts on love, marriage and happiness.

The engravings provide evidence of early religious belief and ritual performances, as well as details of professions, crafts and currencies, and also highlight the professionalism and skill of the engravers, according to Dr. Salma Hawsawi, professor of ancient history at King Saud University in Riyadh.

“Writing is an invention of man,” Hawsawi told Arab News. “It is a means of exchanging ideas and knowledge, as well as discussing it within societies, regardless of class, beliefs and sects.”

She added that historical information gleaned from these inscriptions can reflect the feelings of love, fear, longing, sadness and happiness felt by people at the time.

“That is why inscriptions are seen as a true witness of what the people of that era experienced, which highlights the region’s cultural depth.”

Hawsawi said that writing and engraving were regarded as professions. “Writing, in general, illustrates the level of civilization and education that Arab society reached, and also demonstrates writing’s role in the progress of humanity.”

The existence of writing in civilizations of all kinds is proof of their importance in codification, communication and relations between societies.

Dr. Salma Hawsawi

She said that writing developed through two stages — “the pre-alphabet stage, which is figurative writing, or depicting material things in the human environment to denote moral aspects through rock drawings. Then, after that, symbolic with syllabic sounds.”

Engravings also provided details of tribal names and locations, as well as professions and crafts, trade provisions, currencies, and exports and imports.

According to Hawsawi, cuneiform script spread throughout Mesopotamia from about 3,200 B.C. and was used until A.D.100.

Hieroglyphic script was in use in Egypt by 4,000 B.C., while Ugaritic script was used in northern Syria. Sinaitic script dates back to 1,400 B.C. and was invented by a group of Canaanites working in turquoise and copper mines in the Sinai desert.

Meanwhile, Phoenician script, which dates back to 1,000 B.C., and Punic script spread throughout North Africa from 300 B.C. until A.D. 300.

“The existence of writing in civilizations of all kinds is proof of their importance in codification, communication and relations between societies,” Hawsawi said.

Across the Arabian Peninsula, written inscriptions offer clues to the Arab communities that lived in various areas. Some of the inscriptions had a religious aspect, focusing on the names of gods and religious rituals, while others were more social, discussing personal status, marriage, divorce, and people’s names.

Engravings also provided details of tribal names and locations, as well as professions and crafts, trade provisions, currencies, and exports and imports.

The engravings provide evidence of early religious belief and ritual performances.

“On the political level, inscriptions included the names of kings and rulers, wars and the rise and fall of states,” she said.

“These inscriptions are an important source of historical and cultural knowledge of the region. The spread of these inscriptions and their large number give us an idea of the level of knowledge and culture reached by the societies and the attention they paid to writing and documentation.”

Hawsawi said that inscriptions can be found on rocks in an arranged or random manner, depending on the writer’s skill, as well as on the facades of temples, houses and even gravestones. Some depicted society through famous events or the aphorisms of its rulers.

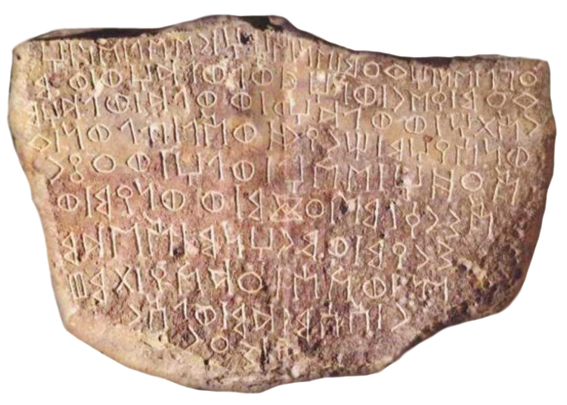

In southern Arabia, Ancient South Arabian script was used from about 800 B.C. the A.D 600. Inscriptions are widespread, and can be found on stones, timber, and bones in eastern Arabia, Al-Faw, Najran and as far north as AlUla.

“The Zabur script also appeared in the south and dates back to about 500 B.C. Some say that the ancient South Arabian script and Zabur script emerged at about the same time,” Hawsawi said.

In the north of the Arabian Peninsula, Thamudic script was in use from 800 B.C. and consisted of 29 characters. Inscriptions have been found on rock facades along the trade route from the far south of the Arab world to the far north.

The Safaitic script is similar to the Thamudic script and dates back to the first century B.C. Dating back to the ninth century, the Aramaic script contains 22 letters, taken from Phoenician writing, and spread widely in the ancient world, especially in Mesopotamia, Iran, India, Egypt and the northern Arabian Peninsula.

Hawsawi pointed out that “the Dadanite and Lihyanite scripts date back to the sixth or fifth centuries B.C. and contain 28 letters, some of which resemble the Thamudic and ancient South Arabian scripts. It is written from right to left and the words are separated by a vertical line. The Palmyrene and Syriac scripts derived from Aramaic date back to the first century B.C. The Nabati script is derived from the Aramaic, however some of its letters have changed in terms of form and adding a dot, giving way to the Arabic script in which we write today.”

She said that writing in Arabian Peninsula societies differed from that of other cultures due to its distinctive scripts and range of topics.

“Life and related events were recorded, unlike other civilizations that focused on codifying political events,” she said.