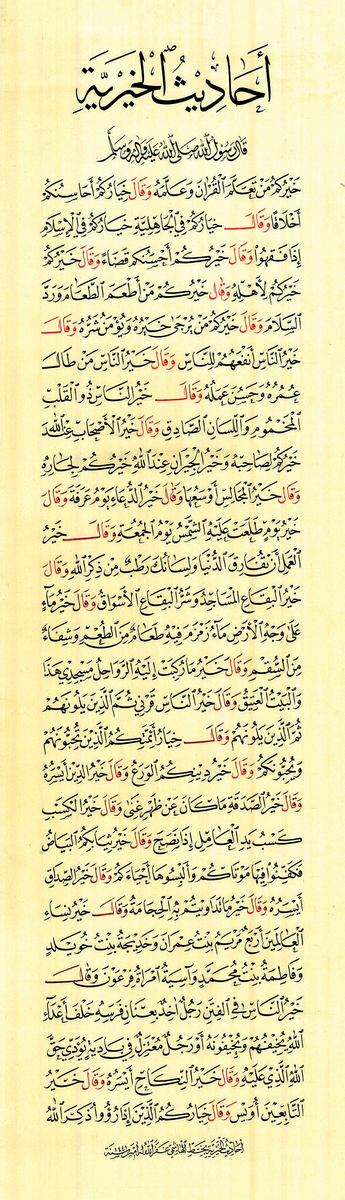

JEDDAH/RIYADH: Arabic calligraphy is an intrinsic part of Islamic civilization. The art form is an integral part of almost all aspects of Arab cultural expression.

Despite its significance in Islamic art and culture, however, its popularity seems to be in decline among the masses. A number of reasons could be suggested for why this is the case, perhaps the most plausible of which is the lack of promotion and visual representation of the Arabic language in the tools of modern technology — most importantly, the internet.

Whatever the reason for the diminishing popular appeal and appreciation of the art form in the modern world, it nevertheless somehow continues to survive in its classical form.

The importance of Arabic calligraphy comes from its connection to the Holy Qur’an, according to Dr. Nassar Mansour (@dr.nassarmansour), a Jordanian-Palestinian artist and calligrapher who teaches Islamic calligraphy and Qur’anic manuscripts at the College of Islamic Arts and Architecture at the World Islamic Science and Education University in Amman, Jordan.

The classical school fears, wrongly, that technology will kill its traditions; the basic skill and the principles of its teaching cannot be lost or eliminated.

Siraj Allaf

The divine nature of the Qur’an compelled Arabs to redesign their script and beautify it, he said, which provided the initial impetus for the development of the art form in the 7th century. Modern technology has had little effect on classical forms of Arabic calligraphy which, he believes, will remain relevant because of its strong bond with the sacred text.

“However, calligraphy’s functional aspect has undoubtedly receded” since the advent of the printing press, he added.

The link between Arabic calligraphy and the Qur’an means its practice is primarily a religious experience, for which a set of rules were developed over the centuries regarding patience and self-discipline. These rules are collectively known as “adab” (manners) among calligraphers, and it is mandatory for instructors and students to follow them.

Siraj Allaf (@sirajallaf), a Saudi artist and engineer, studied calligraphy at the Grand Mosque in Makkah under the supervision of renowned calligrapher Ibrahim Al-Arafi. After years of training, he received his “ijazah,” or diploma, in traditional calligraphy. Studying calligraphy in this way is a rich and rewarding educational experience, especially for young people, he said.

FASTFACT

• Whatever the reason for the diminishing popular appeal and appreciation of the art form in the modern world, it nevertheless somehow continues to survive in its classical form.

• Graduates in classical calligraphy sometimes become ‘too modest’ in their approach to life, which means that they miss out on opportunities to grow and fail to receive the public recognition they deserve.

• Hrofiat is the first Saudi platform for calligraphy through which some of the best calligraphers in the country are working together to promote it through workshops, events and online courses.

“I have learned endless life lessons from my master,” Allaf said. “I always say that I have learned everything from him, and calligraphy comes last on the list.”

Graduates in classical calligraphy sometimes become “too modest” in their approach to life, he added, which means that they miss out on opportunities to grow and fail to receive the public recognition they deserve.

“Their great emotional attachment to their art does not allow them to invest in their talent, because they refrain from using it to make money,” he explained. “If we look at other art forms, such as photography, we find that artists have actually chosen that path to make money in the first place.”

To help raise the profile of the art form, Allaf founded Hrofiat, the first Saudi platform for calligraphy, through which some of the best calligraphers in the country are working together to promote it through workshops, events, online courses, the creation of original and digital works, and the provision of artistic consultancy services.

He said that assembling an elite group of calligraphers was a challenge because some were wary about the idea of making money from their art. Most calligraphers, he believes, adopt a conservative approach to commerce and the adoption of modern techniques; they avoid the use of technology fearing they fear they might lose the “spirit” of their art, which they consider sacred.

Many experts, including Allaf, believe the roots of this reluctance to embrace modern innovations can be traced back to the days of Ottoman rule, during which there was a delay in adopting printing technology as a result of religious and scribal resistance.

As the Ottoman Empire consolidated power from its capital, Constantinople, it acquired print technology, which was common across Europe, as early as 1453. The Ottomans did not, however, officially begin printing until 1726, when Ibrahim Muteferrika opened a printing shop with the blessings of Sultan Ahmed III and the religious authorities.

Therefore, printing did not begin to gain a foothold in the Arab, Ottoman and Islamic worlds until the 18th century, nearly 400 years after its rapid spread across Europe. That had the long-term effect of delaying the adaptation of the ever-evolving technology to meet the specific aesthetic requirements of Arabic calligraphy.

When the use of new printing technology did finally begin to spread, traditional calligraphers began to lose their jobs in newspapers, magazines and other forms of publishing. Many had neither the alternative skills nor tools to adapt and channel their experience in new directions.

As a result, the unparalleled beauty of Arabic calligraphy became mostly banished to art galleries and museums around the world.

Dr. Abdullah Futiny, chairman of Saudi Scholarly Association of Arabic Calligraphy, believes another factor in the declining appreciation for Arabic calligraphy, particularly among the younger generation, is the increasing popularity of computer-generated fonts now used by most people.

This disconnect between the modern masses and the classical form of the art has also discouraged Arabic calligraphers from experimenting with digital tools, he added, in the belief that their traditional approach to the art form is the most pure expression of the Islamic spirit.

Allaf agreed with this analysis, saying: “The classical school fears, wrongly, that technology will kill its traditions; the basic skill and the principles of its teaching cannot be lost or eliminated.

“Some are afraid to accept the fact that many of the techniques they have been practicing for years can now be done with a push of a button.”

Classically trained Yemeni-Turkish calligrapher Zeki Al-Hashimi (@hattatzeki), who studied for the traditional diploma in Turkey, believes the classical school must change and adapt to the demands of the modern world, and embrace the use of new technology. After all, he pointed out, even traditional calligraphy tools evolved over time.

“Some aspects have been less influenced by the passage of time, such as the formal expression of each letter and glyph,” he said. “Therefore, the golden ratio and geometry of the general form of Arabic script is the only traditional factors that we should worry about preserving.”

Allaf and Al-Hashimi agree that modern technology does not pose any threat to the traditions of classical calligraphy.

“Technology is simply a means to further develop the art and promote the culture, not an end in itself,” said Al-Hashimi.

Allaf said calligraphers must work with designers and developers to improve the technical tools that are available, and that such cooperation is required because “individual efforts are no longer efficient.”

Mansour, was also open to the use of new technology but stressed that any integration of Arabic script with modern technology must be carried out by professionals who understand the art and its value, and respect its spiritual and aesthetic aspects.

It is an irony that while there has long been a reluctance to embrace the use of modern technology in Arabic calligraphy, social media might, to some extent, be helping to revive the classical art form and increase its popularity among young people. Mansour and Allaf said that social media, and the other modern tools at their disposal, allow them to teach students in other countries and spread knowledge and appreciation of the art form to a wide audience to an extent that was unimaginable before the digital revolution.

Yet it is the core spiritual values of Arabic calligraphy, through its connection with sacred texts, that continue to encourage young people to explore its mysteries, as a result of their personal experiences.

Al-Hashimi also uses social media to share calligraphy lessons and discuss the art form with followers.

“Though I understand that not all people see the script like professionals do, I try to offer diverse content to suit all segments of society,” he said.

Mansour said that the blame for the decline in awareness and popularity of calligraphy is shared by many, including official institutions, educators and a general failure to promote cultural awareness of the art form.

“Calligraphers are also responsible for this ignorance about the art form and its aesthetic value,” he added.

There is general agreement that the only way to restore the social and cultural status and value of Arabic calligraphy is through long-term institutional projects, with governmental support. An important step, therefore, was the announcement in January by Saudi Culture Minister Prince Badr bin Abdullah that 2020 is the “Year of Arabic Calligraphy.” Another remarkable step taken by the Kingdom is the recent establishment of the Prince Mohammed bin Salman Global Center for Arabic Calligraphy in Madinah, which will include a museum, an exhibition hall, and an institute dedicated to the art form.

“Any creative person, be it a scientist or an artist, regardless of their field, needs a sovereign, empowering decision to have a voice and obtain their right of popular attention,” said Allaf.

Al-Hashimi added: “These giant projects remain important initiatives that not only benefit the country and its people but also serve the wider Arab and Islamic world.”

Futiny called upon people with a talent for calligraphy, in its classical and modern forms, to make good use of their skills and work hard to hone them.

“There are many tasks Arabic calligraphers and Arabic software programmers should carry out to improve the format and shape of Arabic letters for computer users,” he said.

He also highlighted the importance of introducing new, well-designed calligraphy lessons in schools to develop pupils’ handwriting and encourage them to explore and realize their full potential.