KARACHI: Sabika Aziz Shaikh, the Pakistani victim of the Texas school shooting, wanted to join the Foreign Service of Pakistan and improve the image of her country.

This was revealed by her father, Abdul Aziz Shaikh, during an interview with Arab News on Sunday. The 17-year-old Pakistani foreign exchange student, participating in the Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Study (YES) program in the US, was killed along with nine others when a teenage classmate opened fire on fellow students in the Santa Fe High School in Texas on Friday.

When the tragic news reached Sabika’s hometown, her friends, relatives and other people started pouring in to her residence in Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi in order to mourn her death and condole with the bereaved family.

Sabika’s father said that most children dream of becoming doctors or engineers. “Sabika wanted to sit the Central Superior Services (CSS) exams and join the Foreign Service of Pakistan. She thought that Pakistan was a great country, but that it had an image problem.”

“At one point, she told me that she wanted to be like Maleeha Lodhi and Tasneem Aslam,” said Abdul Aziz Shaikh. “Her desire was to improve the image of Pakistan abroad.”

“She was not very studious and did not study for long hours but she was extremely intelligent. She liked to hang out with friends and family and was full of life,” Abdul Aziz Shaikh said.

He recalled the day he took his daughter to a local hospital for a blood test, saying she did not like needles and resisted the idea of being pricked in her arm.

“When I told her that her unwillingness would make it difficult for her to fulfill her dream of studying in the US, she gave in. But she cried while they were taking her blood,” he said in a state of grief, adding: “She was so scared of needles. It’s hard for me to imagine what she must have thought on hearing gunshots that fateful day.”

“Was she crying at that moment, taking my name or thinking of her mother? I haven't been able to get these thoughts out of my mind ever since hearing the news of her death,” Abdul Aziz Shaikh said in a feeble voice.

“Daughters are usually closer to their fathers. but Sabika was also the darling of her mother. She had close attachments to everyone. And my youngest daughter, Soha, has lost her best buddy,” he said.

Soha recalled her last conversation with Sabika as she spoke to Arab News. On Thursday, her sister had said that she would be back in Pakistan after 19 days. “She told me that she had bought gifts for us, asking me if I wanted anything specific from the US,” said Soha.

She was fond of Pakistani cuisine. “She told me that she wanted to have Bismillah Biryani – from our old neighborhood of Shah Faisal – when she came back to the country,” Soha said.

“She was fasting when she was shot,” Abdul Aziz Shaikh continued. “She wanted to fast for the whole month.”

Ali Aziz, Sabika’s brother, told Arab News that she “was among the 75 students who got selected for the exchange program out of five thousand applicants.”

“She made us proud and didn’t put any financial burden on her family since winning the prestigious scholarship. She was very excited and happy when she left for the US. She left her O Level incomplete and was planning to continue it on her return,” Abdul Aziz Shaikh said.

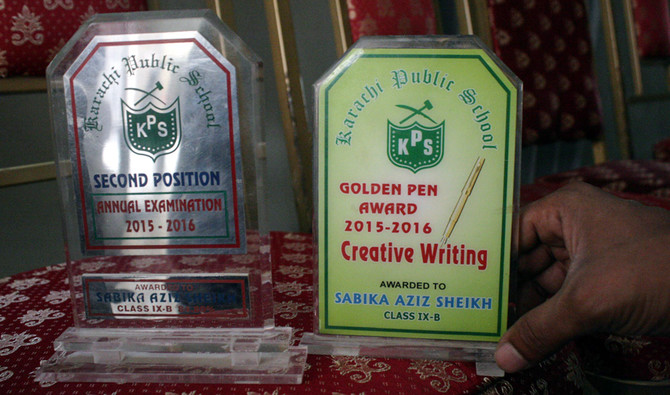

Talking to the media outside Sabika’s residence in Karachi, Shehla Shamim, principal of the Karachi Public School, said that Sabika was a position holder.

“She was not just a student but a representative of Pakistan. She was proud of going to the US and told me that she wanted to carry Pakistani culture to that country with her,” she said.

Her father told Arab News that Sabika’s body had been handed over to the Muslim community and would be sent to Pakistan soon.

“We will offer her funeral prayer on Tuesday morning,” he said.

Sabika wanted to improve Pakistan's image abroad, says her father

Sabika wanted to improve Pakistan's image abroad, says her father

- Seventeen-year-old Pakistani girl wanted to be a diplomat and improve her country’s image abroad.

- Her father says she wanted to be like Tasneem Aslam and Maleeha Lodhi.

Afghan returnees in Bamiyan struggle despite new homes

- More than five million Afghans have returned home since September 2023, according to the International Organization for Migration

BAMIYAN, Afghanistan: Sitting in his modest home beneath snow-dusted hills in Afghanistan’s Bamiyan province, Nimatullah Rahesh expressed relief to have found somewhere to “live peacefully” after months of uncertainty.

Rahesh is one of millions of Afghans pushed out of Iran and Pakistan, but despite being given a brand new home in his native country, he and many of his recently returned compatriots are lacking even basic services.

“We no longer have the end-of-month stress about the rent,” he said after getting his house, which was financed by the UN refugee agency on land provided by the Taliban authorities.

Originally from a poor and mountainous district of Bamiyan, Rahesh worked for five years in construction in Iran, where his wife Marzia was a seamstress.

“The Iranians forced us to leave” in 2024 by “refusing to admit our son to school and asking us to pay an impossible sum to extend our documents,” he said.

More than five million Afghans have returned home since September 2023, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as neighboring Iran and Pakistan stepped up deportations.

The Rahesh family is among 30 to be given a 50-square-meter (540-square-foot) home in Bamiyan, with each household in the nascent community participating in the construction and being paid by UNHCR for their work.

The families, most of whom had lived in Iran, own the building and the land.

“That was crucial for us, because property rights give these people security,” said the UNHCR’s Amaia Lezertua.

Waiting for water

Despite the homes lacking running water and being far from shops, schools or hospitals, new resident Arefa Ibrahimi said she was happy “because this house is mine, even if all the basic facilities aren’t there.”

Ibrahimi, whose four children huddled around the stove in her spartan living room, is one of 10 single mothers living in the new community.

The 45-year-old said she feared ending up on the street after her husband left her.

She showed AFP journalists her two just-finished rooms and an empty hallway with a counter intended to serve as a kitchen.

“But there’s no bathroom,” she said. These new houses have only basic outdoor toilets, too small to add even a simple shower.

Ajay Singh, the UNHCR project manager, said the home design came from the local authorities, and families could build a bathroom themselves.

There is currently no piped water nor wells in the area, which is dubbed “the dry slope” (Jar-e-Khushk).

Ten liters of drinking water bought when a tanker truck passes every three days costs more than in the capital Kabul, residents said.

Fazil Omar Rahmani, the provincial head of the Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation Affairs, said there were plans to expand the water supply network.

“But for now these families must secure their own supply,” he said.

Two hours on foot

The plots allocated by the government for the new neighborhood lie far from Bamiyan city, which is home to more than 70,000 people.

The city grabbed international attention in 2001, when the Sunni Pashtun Taliban authorities destroyed two large Buddha statues cherished by the predominantly Shia Hazara community in the region.

Since the Taliban government came back to power in 2021, around 7,000 Afghans have returned to Bamiyan according to Rahmani.

The new project provides housing for 174 of them. At its inauguration, resident Rahesh stood before his new neighbors and addressed their supporters.

“Thank you for the homes, we are grateful, but please don’t forget us for water, a school, clinics, the mobile network,” which is currently nonexistent, he said.

Rahmani, the ministry official, insisted there were plans to build schools and clinics.

“There is a direct order from our supreme leader,” Hibatullah Akhundzada, he said, without specifying when these projects will start.

In the meantime, to get to work at the market, Rahesh must walk for two hours along a rutted dirt road between barren mountains before he can catch a ride.

Only 11 percent of adults found full-time work after returning to Afghanistan, according to an IOM survey.

Ibrahimi, meanwhile, is contending with a four-kilometer (2.5-mile) walk to the nearest school when the winter break ends.

“I will have to wake my children very early, in the cold. I am worried,” she said.

Rahesh is one of millions of Afghans pushed out of Iran and Pakistan, but despite being given a brand new home in his native country, he and many of his recently returned compatriots are lacking even basic services.

“We no longer have the end-of-month stress about the rent,” he said after getting his house, which was financed by the UN refugee agency on land provided by the Taliban authorities.

Originally from a poor and mountainous district of Bamiyan, Rahesh worked for five years in construction in Iran, where his wife Marzia was a seamstress.

“The Iranians forced us to leave” in 2024 by “refusing to admit our son to school and asking us to pay an impossible sum to extend our documents,” he said.

More than five million Afghans have returned home since September 2023, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as neighboring Iran and Pakistan stepped up deportations.

The Rahesh family is among 30 to be given a 50-square-meter (540-square-foot) home in Bamiyan, with each household in the nascent community participating in the construction and being paid by UNHCR for their work.

The families, most of whom had lived in Iran, own the building and the land.

“That was crucial for us, because property rights give these people security,” said the UNHCR’s Amaia Lezertua.

Waiting for water

Despite the homes lacking running water and being far from shops, schools or hospitals, new resident Arefa Ibrahimi said she was happy “because this house is mine, even if all the basic facilities aren’t there.”

Ibrahimi, whose four children huddled around the stove in her spartan living room, is one of 10 single mothers living in the new community.

The 45-year-old said she feared ending up on the street after her husband left her.

She showed AFP journalists her two just-finished rooms and an empty hallway with a counter intended to serve as a kitchen.

“But there’s no bathroom,” she said. These new houses have only basic outdoor toilets, too small to add even a simple shower.

Ajay Singh, the UNHCR project manager, said the home design came from the local authorities, and families could build a bathroom themselves.

There is currently no piped water nor wells in the area, which is dubbed “the dry slope” (Jar-e-Khushk).

Ten liters of drinking water bought when a tanker truck passes every three days costs more than in the capital Kabul, residents said.

Fazil Omar Rahmani, the provincial head of the Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation Affairs, said there were plans to expand the water supply network.

“But for now these families must secure their own supply,” he said.

Two hours on foot

The plots allocated by the government for the new neighborhood lie far from Bamiyan city, which is home to more than 70,000 people.

The city grabbed international attention in 2001, when the Sunni Pashtun Taliban authorities destroyed two large Buddha statues cherished by the predominantly Shia Hazara community in the region.

Since the Taliban government came back to power in 2021, around 7,000 Afghans have returned to Bamiyan according to Rahmani.

The new project provides housing for 174 of them. At its inauguration, resident Rahesh stood before his new neighbors and addressed their supporters.

“Thank you for the homes, we are grateful, but please don’t forget us for water, a school, clinics, the mobile network,” which is currently nonexistent, he said.

Rahmani, the ministry official, insisted there were plans to build schools and clinics.

“There is a direct order from our supreme leader,” Hibatullah Akhundzada, he said, without specifying when these projects will start.

In the meantime, to get to work at the market, Rahesh must walk for two hours along a rutted dirt road between barren mountains before he can catch a ride.

Only 11 percent of adults found full-time work after returning to Afghanistan, according to an IOM survey.

Ibrahimi, meanwhile, is contending with a four-kilometer (2.5-mile) walk to the nearest school when the winter break ends.

“I will have to wake my children very early, in the cold. I am worried,” she said.

© 2026 SAUDI RESEARCH & PUBLISHING COMPANY, All Rights Reserved And subject to Terms of Use Agreement.