When her son died fighting for Daesh, British mother Nicola Benyahia channelled her grief into helping other families halt the radicalisation of loved ones. She vividly remembers how, telephoning from the battlefields of Syria, Rasheed sounded increasingly troubled.

The conviction that had driven the 19-year-old to leave his family in Birmingham, England, and take up arms for Daesh, seemed to be wavering.

“You could tell he was beginning to see some grey areas,” his mother, Nicola, told Arab News.

The family wondered if he might be considering returning home, but weeks later received the call they had been dreading. This time an anonymous voice at the end of the telephone line said that Rasheed had died after being hit by shrapnel during a coalition drone strike across the border in Iraq.

The call came on Nov. 20, 2015, one week after Daesh militants killed 130 people during a series of horrific attacks across Paris. Shame mingled with grief as Nicola reeled from the shock.

“The grieving process is very different,” she recalled. “There is no body, no funeral, no closure.”

Rasheed’s transformation from a gregarious, athletic schoolboy brought up in one of England’s most diverse and vibrant cities to a volunteer for an extremist group known for carrying out public beheadings and crucifixions is a salutary lesson for parents across Europe and the Middle East.

Even with Daesh seemingly defeated in Iraq and Syria, the deceptively idealistic beliefs the extremist group espouses remain a potent threat to vulnerable young Muslim men and women. Nicola is determined that other mothers learn from her experience.

She told Arab News that looking back she can see clear warning signs that her son was being radicalized as he grew increasingly serious and withdrawn. “I was worried about him,” she said.

She told Arab News that looking back she can see clear warning signs that her son was being radicalized as he grew increasingly serious and withdrawn. “I was worried about him,” she said.

Like many parents of teenagers, however, Nicola brushed his unusual behavior aside — a decision she now regrets.

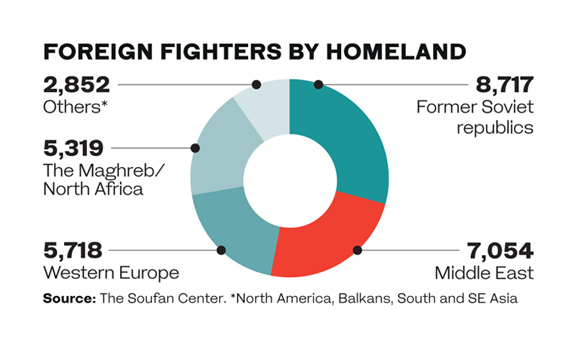

Rasheed was among thousands of foreign fighters who joined Daesh in the aftermath of the 2011 Arab Spring. He arrived at the height of the group’s bloody campaign to preserve its self-proclaimed caliphate, which at its peak in 2014 spanned more than 66,000 square kilometers across Syria and Iraq.

Many of these militants are now expected to try to make their way home and European governments are divided over how best to deal with the potential threat they pose.

Months before his departure from the UK, Rasheed spent money he had saved from his electrical engineering apprenticeship on a diamond necklace for his mother. The accompanying note read: “Mama — no matter how much gold and how many precious stones are used, it’s never enough to show how precious you are to me.”

Nicola believes that was the point Rasheed decided to go. He left Birmingham on a Friday at the end of May 2015, heading out of the family home in the early morning, apparently with routine plans to see friends later. Instead, he boarded a flight to Turkey before traveling to Syria.

On June 1, 2015, three days after he went missing, Rasheed sent his mother a text message. He was “safe” he said, and “in good hands.”

But Nicola’s initial relief gave way to panic as she realized where he was. Rasheed told her he would be out of touch for 30 days and then his phone went dead. It was two excruciating months before they heard from him again.

Based on information she later received from a journalist in contact with Daesh fighters, Nicola found out that he spent those first two months — double the usual amount of time — in the extremist group’s training camps.

“(The militants) said he looked ever so young and ever so lost, but he was very hard work, incredibly difficult to break,” she said.

In WhatsApp calls, Rasheed gave his mother sobering details of life as a Daesh recruit. He told Nicola that fighters were expected to buy their own own military clothing and ammunition, and had to make do with a wage equivalent to $57 a week, barely enough to live on.

He also told her he had been introduced to a woman he was expected to marry, something that he was both nervous and excited about.

According to the Soufan Center, a US-based think tank, 850 Britons have gone to fight in Syria or Iraq. Of those, 425 are estimated to have returned to the UK. This compares with a total of 5,000 recruits who have gone to fight from the EU, 1,200 of whom are estimated to have returned to their home countries.

In the Middle East, Rasheed was given the nom de guerre Huraira Albritani, but his precise role in Daesh remains unclear. He was killed on Nov. 10, 2015 — 10 days before his family were notified — in Sinjar, northern Iraq, just before Kurdish forces backed by US air power wrested control of the area from the militants.

Exactly who carried out the drone strike is not known. However, Rasheed was not the first or the last British Daesh recruit to be killed in this way.

On Aug. 21, 2015, Reyyad Khan, a 21-year-old from Cardiff, Wales, and Ruhul Amin, a 26-year-old raised in Aberdeen, Scotland, died in a RAF drone strike on the Syrian city of Raqqa. Mohammed Emwazi, better known as the Daesh executioner “Jihadi John,” was killed in a drone strike in Raqqa two days after Rasheed.

In the months following her son’s death, Nicola, Rasheed’s father and their four daughters nursed their grief in private. “Your life has been shattered into 50 million pieces, so you try to make some sense of it,” she told Arab News.

A year later, however, Nicola decided to break her silence to help others avoid the same tragedy. Already a professional therapist, she trained under Daniel Koehler, director of the German Institute on Radicalization and De-radicalization Studies, and, in 2016, set up Families for Life, a Birmingham-based outreach group.

She has since supported families from Europe, the UAE and the US who are dealing with the radicalization of a loved one. Most, she told Arab News, have “no idea” what is going on until the damage is done.

In one case, a mother was worried her son had begun to fast regularly — rationing his meals to one a day. Nicola warned her that it could be a sign he was preparing for the austere conditions he might face fighting for Daesh in the Middle East. She had witnessed similar changes in Rasheed, who went from loving free running — urban acrobatics where walls, bus shelters and park benches become gym apparatus — and doing handstands in the school corridor to becoming sullen and solitary.

Nicola converted to Islam in her late teens and later married an Algerian, but has always been relatively moderate in her beliefs. When Rasheed grew “more rigid” in his faith, Nicola attributed it to recent marital difficulties with her husband that had upset the family home.

Nicola converted to Islam in her late teens and later married an Algerian, but has always been relatively moderate in her beliefs. When Rasheed grew “more rigid” in his faith, Nicola attributed it to recent marital difficulties with her husband that had upset the family home.

“I thought he was holding on to religion because it helped him find a way through, as it had me in the past,” she said.

Rasheed stopped attending their mosque and changed the way he dressed, once asking her to shorten his trouser legs in line with strict Salafi practice that seeks to mimic the clothing style of the Prophet Muhammad and his earliest followers. Rasheed also wanted to attend late-night Islamic study circles, but his mother refused to let him.

Nicola believes the safest solution to dealing with British foreign fighters is to encourage them to return home, where they can be rehabilitated and help to provide the government with further insight into how Daesh operates.

“Counter-terrorism learnt huge amounts from the information I was able to share with them from my son … if we don’t allow them back, we’re not going to access that data, which could be crucial,” she told Arab News.

Nicola never discovered who was responsible for recruiting her son, but the name of a likely suspect surfaces time and again during her work with other families. That person is still at large. The recruiters are clever, she said, because “they know how to fly just below the radar.”

It took weeks for Nicola to piece together the picture of Rasheed’s final months and much remains unknown, but she no longer dwells on these details. Instead, she hopes to use the lessons she has drawn from her son’s death to save the lives of other young men and women who may be tempted to follow in his footsteps.

“You can very easily spiral into negativity and grief, but I would be no good for anybody if I let that happen,” she said. “It would be almost like letting them win again.”