BEIRUT: Efforts by American diplomats to broker a ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah in southern Lebanon have hit a dead end, leaving the region perched on the edge of a full-blown war.

Since the eruption of hostilities on Oct. 8 last year, both sides have intensified their defense preparations, with leaks and official statements signaling that the Israeli military has authorized operational plans for strikes within Lebanese territory.

Meanwhile, reports carried by Hezbollah-aligned media outlets indicate that the powerful Shiite group has prepared extensively for a potential Israeli offensive, planning to counter various military scenarios and thwart attacks on Lebanese soil.

Lebanon, already weighed down by deep political divisions and a crumbling economy, now faces the specter of a devastating conflict that could tear apart its fragile unity. As diplomatic solutions falter, the prospect of war looms larger, raising grave concerns among Lebanese citizens and the international community alike.

Recent footage released by Hezbollah, showing aerial views of Israeli military installations captured by a Hudhud (hoopoe) drone, underscores the group’s formidable capabilities. However, images of Gaza, devastated by repeated Hamas-Israel conflicts, serve as a stark warning of the potential human and economic toll of renewed warfare.

Members of Israeli security forces inspect sites where rockets launched from southern Lebanon fell in Kiryat Shmona in northern Israel near the Lebanon border, on June 19, 2024. (AFP)

Since Oct. 8, the Lebanon-Israel border has witnessed almost daily exchanges of fire between Hezbollah and allied Palestinian militant groups and Israel’s military that have left more than 400 people dead in Lebanon.

Most of the fatalities were fighters and commanders, but they also included more than 80 civilians and non-combatants. On the Israeli side, 16 soldiers and 11 civilians have been killed over the past eight months.

Against this tense backdrop, Hezbollah’s actions affect not only Lebanon but also regional stability, hence its ability to avert or deal with a direct military confrontation with Israel will be crucial in the days ahead.

Last week Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah warned Cyprus against allowing Israel’s military to use its airports on the island to bomb Lebanon should a full-blown war break out. This created a diplomatic crisis of sorts as Cyprus and Lebanon have had close and historic relations for decades, with the island hosting thousands of Lebanese during Lebanon’s 1975-90 civil war.

Adding to the sense of impending doom are growing signs of international alarm. Several embassies and diplomatic missions in Lebanon have issued advisories urging their citizens to leave immediately, citing escalating tensions and the risk of broader conflict.

Kuwait’s recent decision to advise against travel to Lebanon reflects a wider trend of concern among foreign governments.

Lebanon’s internal turmoil accentuates its vulnerability. The country has been without a president for nearly two years, relying on a caretaker government unable to make critical decisions amid rampant corruption and economic collapse.

More than half of Lebanon’s population now depends on aid for survival, while the remainder struggles to secure basic necessities such as education, fuel and electricity.

This photograph taken on January 8, 2024 shows a banner depicting Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah hanging on the building, which was hit by a drone attack on January 2, 2024. (AFP)

The gravity of Lebanon’s predicament was underscored by recent developments at Beirut’s Rafik Hariri International Airport. Reports in the UK’s Telegraph newspaper suggested that Hezbollah was using the airport to smuggle large quantities of Iranian weaponry, including short-range missiles — a claim that could potentially make the facility a target for Israeli airstrikes.

In Washington, President Joe Biden’s administration has reportedly reassured Israeli officials of unwavering US support, promising to provide Israel with all necessary security assistance.

This commitment comes amid reports of heightened military movements, including the deployment of an aircraft carrier to the Eastern Mediterranean — a move interpreted as a show of force and readiness to back Israel in any military confrontation.

Antonio Guterres, the UN secretary-general, has issued a stark warning against Lebanon descending into the chaos and destruction witnessed in Gaza. The international community’s fear is palpable, as another conflict in Lebanon could unleash humanitarian and geopolitical consequences that would reverberate across the Middle East and beyond.

Emergency and security service members and residents gather around a car at the site of an Israeli strike in Al-Khiyara town in Lebanon’s Western Bekaa area on June 22, 2024. (AFP)

According to Harith Slieman, an academic and political analyst, Lebanon has effectively been in a state of war since Oct. 8. He believes that in the coming days, Israel may not seek a ground invasion of Lebanon, but could ratchet up hostilities through continued airstrikes, targeting infrastructure that would inflict significant damage.

“The missiles Israel intends to launch are more costly than the facilities they will destroy,” Slieman told Arab News, dismissing the notion of a “balance of terror” maintained by Hezbollah to forestall war.

“Hezbollah’s drones, such as the Hudhud, primarily gather intelligence rather than posing a direct security threat to Israel,” he said.

Slieman also rejects comparisons between Israel’s 1970s-80s-era conflict with the Palestinian Liberation Organization and its current standoff with Hezbollah, arguing that the former was viewed as an existential threat whereas the latter is rooted in security concerns.

An Israeli air force multirole fighter aircraft flies over the border area between northern Israel and southern Lebanon on June 21, 2024. (AFP)

Regarding the displacement of nearly 60,000 residents of northern Israel caused by the cross-border fighting with Hezbollah, Slieman said this was a decision prompted by Israeli fears of an assault similar to the Hamas-led attack of Oct. 7 on southern Israel.

He believes that even if Israel pushes Hezbollah north of the Litani River, it would not be able to eliminate the threat to its security entirely. Instead, he suggests, Israel’s strategy aims to exert military pressure on Hezbollah to force negotiations that could relocate its citizens back to safer northern areas, in a tacit acknowledgement of Hezbollah’s entrenched presence in southern Lebanon.

Slieman nevertheless paints a bleak picture of Lebanon’s governance, describing it as in a state of collapse, with Hezbollah wielding substantial influence, Najib Mikati operating as a caretaker prime minister, and Nabih Berri, the parliament speaker, remaining politically beholden to the pro-resistance faction.

He says dealing with the Hezbollah question is a fundamentally internal political matter, and therefore only Lebanese stakeholders can resolve the underlying tensions.

This picture taken late on June 23, 2024 shows Israeli bombardment on the village of Khiam in south Lebanon near the border with Israel. (AFP)

Political observers say Hezbollah’s outsized role in Lebanese politics and its broader regional ambitions complicate efforts to achieve lasting peace. Since the 2006 war with Israel, the group has solidified its position, emerging as a key player in domestic governance and a formidable force in regional conflicts such as Syria’s civil war.

Charles Jabour, head of the Lebanese Forces party’s media and communications wing, laments the deepening polarization within Lebanese society.

Since the withdrawal of Syrian forces in 2005, the country has struggled to forge a unified national identity, with Hezbollah’s influence often seen as exacerbating sectarian tensions.

“The division is stark,” Jabour told Arab News. “Attempts to elect a president have repeatedly faltered, as Hezbollah asserts its own agenda independently of the state.”

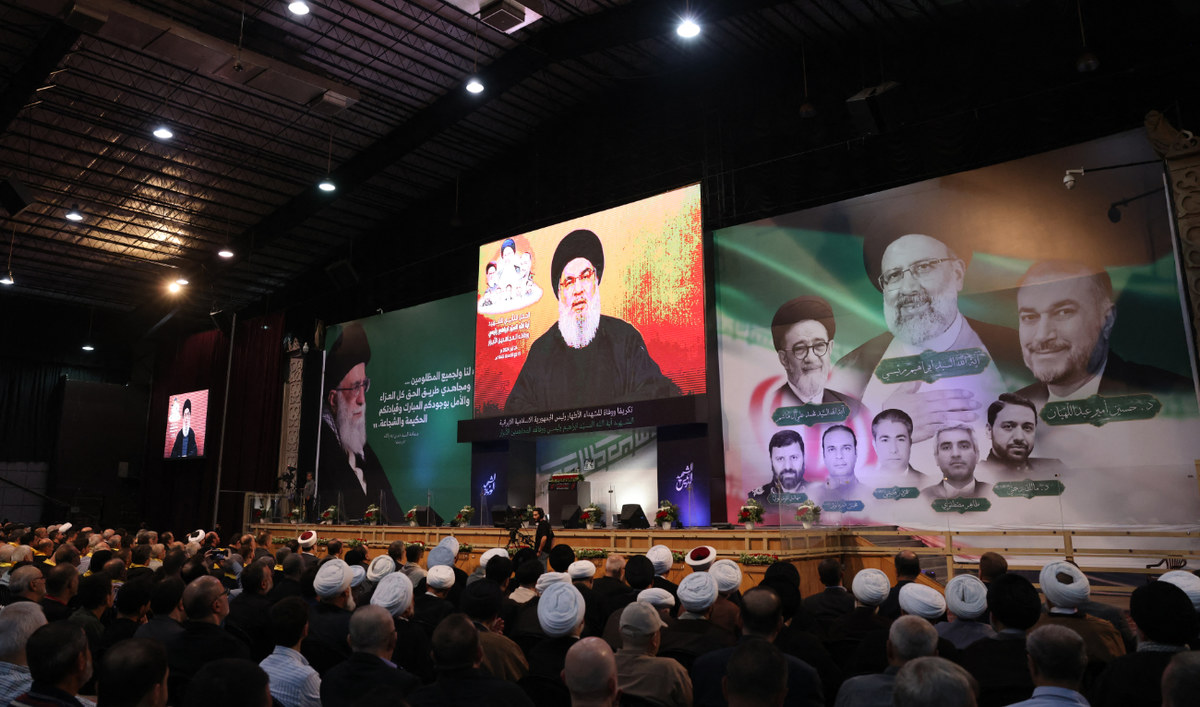

Nasrallah, seen here delivering a live-streamed address, has ratcheted up the rhetoric of war in response to the elimination of numerous Hezbollah commanders. (AFP)

Hezbollah’s actions and alliances have also invited international scrutiny and condemnation. Its rejection of the international tribunal investigating the 2005 assassination of former Prime Minister Hariri, coupled with allegations of involvement in illicit activities like drug smuggling and money laundering, have further isolated Lebanon on the global stage.

The threat of war has prompted religious leaders to convene urgent meetings, seeking to address the growing crisis and its potential ramifications. From the headquarters of the Maronite patriarchate, leaders from across Lebanon’s religious spectrum recently called for unity and calm.

In a recent interview with Al-Hadath, Raghida Dergham, founder of the Beirut Institute, warned of Lebanon’s dangerous geopolitical trajectory, highlighted the interconnectedness of regional dynamics, particularly Hezbollah’s ties to Iran and its broader influence across the Middle East.

She said the problem now is one of interpreting Hezbollah’s claim that there is a connection between Gaza and Lebanon. Hamas leader “Yahya Sinwar has 120 hostages while Hassan Nasrallah has 4 million hostages,” Dergham told the current-affairs Arabic TV channel. “The situation is becoming dangerous. What may stop the Lebanon-Israel war is Iran more than America.”

Elaborating on the claim, she said: “As Iran is currently not ready to wage war with Israel and wishes to reconcile with the US administration, I think that Nasrallah worries that some deals are being done behind his back. Therefore, he has got to be extra careful in the way he goes about the matter.”

As Lebanon braces for what many fear is an inevitable conflict, the international community grapples with how best to avert or mitigate the crisis. Calls for diplomatic intervention and mediation grow louder, yet the complex web of regional alliances and historical grievances complicates efforts to find a peaceful resolution.

For now, Lebanon remains on the brink — a nation hamstrung by its own divisions and external pressures. The path forward is uncertain, with the fate of millions hanging in the balance.

As the world watches, hoping for a reprieve from the drums of war, Lebanon’s destiny seems inexorably intertwined with the volatile geopolitics of the Middle East.