DHAHRAN: The first thing that strikes you when you meet the creative duo Fatimah Al-Dubais and her artist husband Mohammad Al-Madan is how much they love merging Japanese aesthetics with Saudi sensibilities. It would not be unusual for one to have an engaging conversation with them about Japanese-related matters while they each keep their hands busy. Her, elegantly folding vibrantly-colored paper rapidly into a crane as she talks, and him, sketching with his signature anime-style drawing as he responds. Their love for Japanese art runs deep — all while always maintaining their Saudi roots.

Both Al-Dubais and Al-Madan grew up in the Eastern Province; they each independently grew a fascination for Japanese art from a young age — Al-Dubais with origami, Al-Madan with anime and manga. They met in the creative world in 2016 and have since become partners in life and in work.

“We are known in our Saudi friend circle as the ‘Japanese art couple’,” Al-Madan told Arab News with a smile.

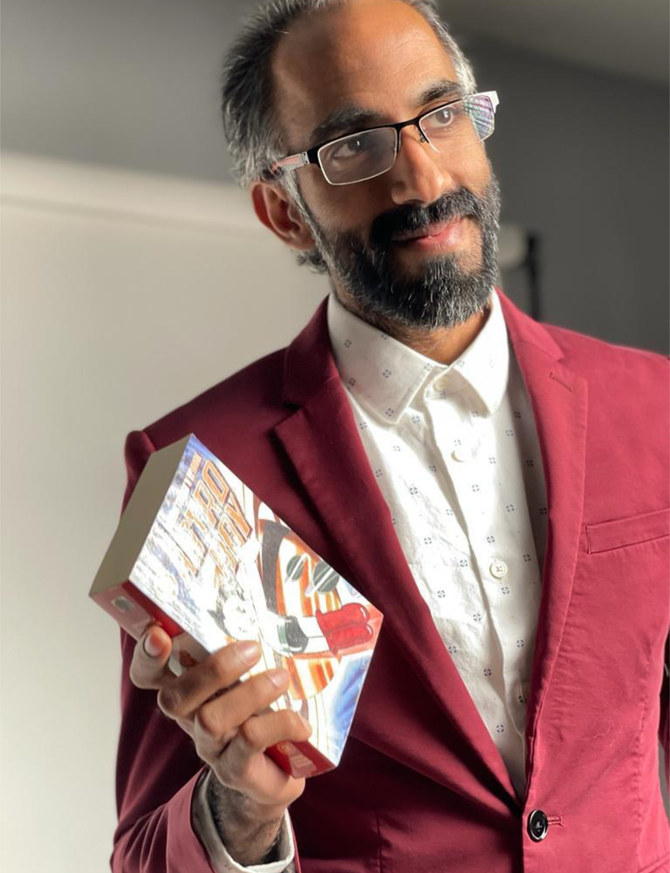

Fatimah Al-Dubais and her artist husband Mohammad Al-Madan’s love for Japanese art runs deep, while always maintaining their Saudi roots. (Supplied)

Indeed, the creative couple have been adamant about spreading their version of Japanese-inspired art in the Kingdom for the last seven years, teaching hundreds of students workshops and offering personalized guidance for locals who want to merge their chosen traditional Japanese art forms — all while still keeping it fresh and “Saudi.”

The story unfolded when Al-Dubais was about 12 years old in Saihat City in 2010. A student she did not know was creating little cranes made of paper and gifting them to other girls at school. Although she never received one herself, Al-Dubais was instantly fascinated. The idea of taking a mundane everyday item like paper and using just your hands to transform it into something else entirely intrigued her, but she did not know what the art form was called.

HIGHLIGHTS

• Both Fatimah Al-Dubais and Mohammad Al-Madan grew up in the Eastern Province and became fascinated by Japanese art from a young age.

• They bonded professionally over their love of Japanese art and their interest in finding creative ways to weave their Saudi identity into their works.

• The pair have worked on many collaborations, using local materials like parts extracted from a palm tree to make art.

YouTube had just started to become popular that year and Al-Dubais had to ask her parents for permission to make a search. As soon as she went online, she tried to look up paper-related art but she could not find the right keyword. Then one day, the algorithm showed her a thumbnail of an origami video and she clicked it. That is how her journey into origami started.

She then spent hours and hours teaching herself how to shape little pieces of paper at home into small works of art. Her mother, who constantly encouraged her to explore new art forms and to be creative, told her to keep at it. So, she did.

Fatimah Al-Dubais and her artist husband Mohammad Al-Madan’s love for Japanese art runs deep, while always maintaining their Saudi roots. (Supplied)

“My mother was my biggest supporter when I was starting to learn origami. Many people around me told me stuff like ‘what are you doing, just folding paper over and over, that isn’t even artistic!’ I enjoyed it, though, and my mother told me to ignore them. It was ‘something’ and soon, they’d know it,” Al-Dubais told Arab News.

And, soon enough, people did. In 2013, after years of making little paper pieces of art in her bedroom, Al-Dubais’ mother told her she had a surprise. Her mother had spoken to some local artists in Saihat and told Al-Dubais to pack some of her paper creations — they were going to show them off at an art show. It was the first time she felt like a legitimate artist and that her works were worthy of being showcased. She learned a lot from that experience and the interaction with other artists encouraged her to become a full-time artist. A year later, in 2014, she started to buy proper origami paper when a new store opened up not too far from her hometown. Every Thursday, she would make a trip there to buy some paper. Then, she started to order from Amazon.

Going to Japan — a place that inspired our work and our lives, even from this distance — would be a dream.

Fatimah Al- Dubais, and Mohammad Al-Madan Saudi artists

While still in high school, Al-Dubais began teaching workshops related to origami, and after she graduated in 2015, she decided to go all in.

When talking to locals about her love of origami, she met a gentleman who worked between Saudi Arabia and Japan and asked if she would like an introduction to the Japanese Embassy in Riyadh. Al-Dubais’ mother accompanied her to the Kingdom’s capital, where she spoke to people about her art and gained confidence to continue learning the craft professionally.

Meanwhile, Al-Madan, who is a few years older than Al-Dubais, grew up not far from her hometown and also had a love of Japanese art — but it was more focused on manga and anime. He was always a creative child and also grew up in a creative family who worked with their hands.

Fatimah Al-Dubais and her artist husband Mohammad Al-Madan’s love for Japanese art runs deep, while always maintaining their Saudi roots. (Supplied)

“In 2016, I was leading an art workshop in Qatif and needed some assistance. Mohammad — who is now my husband — was a volunteer,” Al-Dubais said with a giggle. They bonded professionally over their love of Japanese art and their interest in finding creative ways to weave their Saudi identity into their works.

Al-Madan, who was studying in the US at the time, went back to university. Although his major was in business management, he took art classes on the side just for fun.

“I took an animation class and developed my own style which I use today,” he said.

Upon his return, he proposed to Al-Dubais. It was at the height of the pandemic so they had to keep their wedding very small. After that, their lives centered on Japanese-inspired art.

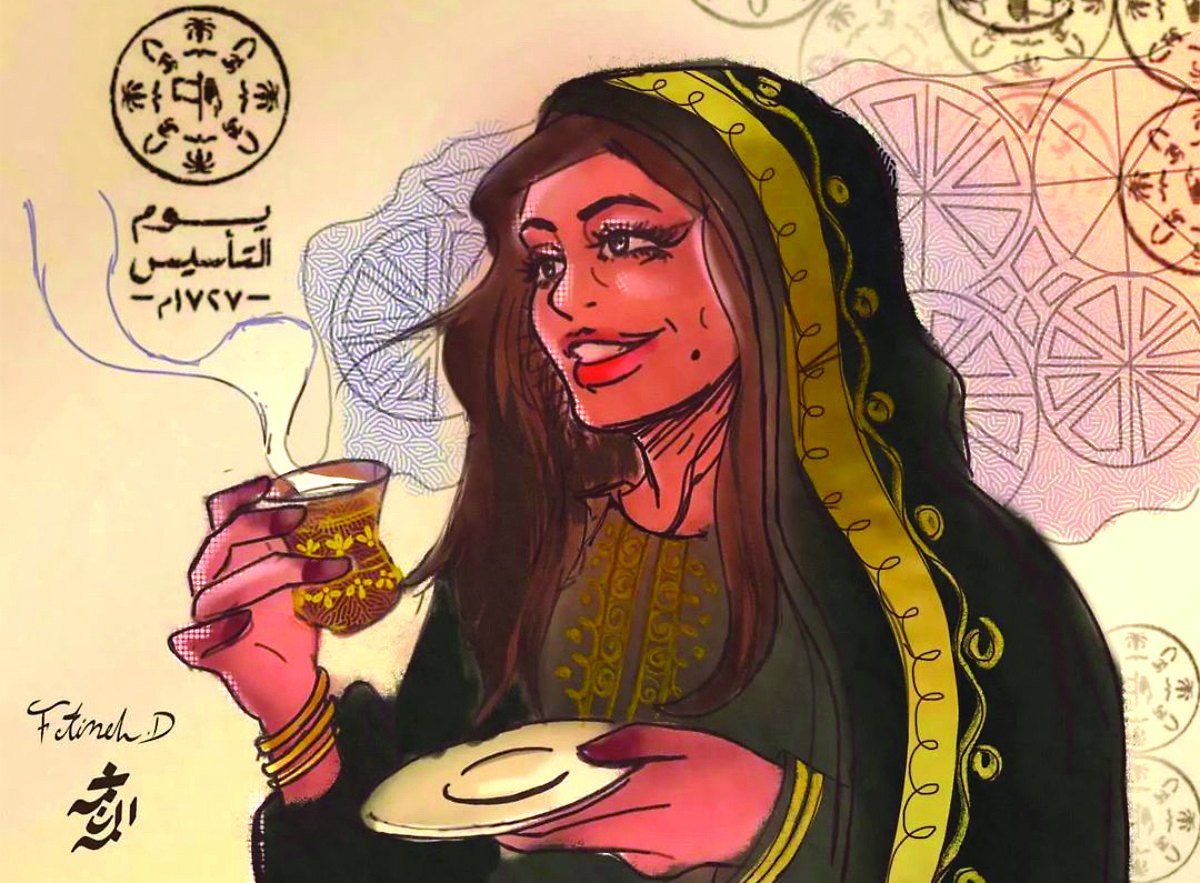

Speaking about her husband’s artwork, Al-Dubais said: “Not because he’s my husband, but I really like his style! It has elements of anime but is a bit more realistic, like the features look a bit more real. He will talk to you and pay attention to what you are saying while his hands draw you at the same time. It is his way of communicating.”

They both used to create art the old-fashioned way, with paper, but have now pivoted to digital mediums. The couple rarely start with paper anymore, since it is more practical and efficient to do most things electronically, saving time and energy, as well as materials.

The pair have worked on many collaborations since, using local materials like parts extracted from a palm tree to make art.

Last year, they worked on a giant origami-inspired owl art piece at a local cafe in Saihat, named Sova, which became the talk of the town. Sova, which means owl in Ukrainian, became a physical manifestation that combined their skills to create a large-scale art piece that locals could interact with.

They also collaborated on many workshops at Ithra in Dhahran, and at Hayy Jameel on the opposite coast in Jeddah. So far, the couple have taught hundreds of students by hosting events in most major cities within the Kingdom.

But they are still looking to learn and create. A missing piece still remains: They have never visited Japan to experience the art forms they now center their lives around.

“We got married during (the pandemic) and our plan was to go to Japan for our honeymoon, but that still didn’t work out. Hopefully we will get a chance to go, to visit or study. Going to Japan — a place that inspired our work and our lives, even from this distance — would be a dream,” the couple said.