JUBA, South Sudan: The government of South Sudan has expressed deep concern over the fighting in neighboring Sudan, which it fears could spill across the border and threaten its fragile peace process.

The clashes between the Sudanese army and a paramilitary group in Khartoum hold the potential to ignite a civil war, into which neighboring South Sudan could get sucked.

Camps for internally displaced people in South Sudan, such as this one in the northern city of Bentiu, risk being swamped further by people fleeing the war in neighboring Sudan. (AFP)

There have been multiple truce efforts since fighting broke out on April 15 between Sudan’s army led by Gen. Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces commanded by his deputy turned rival, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo.

As close neighbors, with a long history of conflict and interdependence, any instability or escalation of violence in Sudan is likely to spill over into South Sudan, with potentially dire consequences.

One major concern for South Sudanese officials is the potential economic impact of a prolonged conflict to the north.

Sudan exports crude oil produced by South Sudan. Any disruption to this trade arrangement could lead to economic instability for the young republic, which has already suffered the knock-on effects of recent tribal uprisings in eastern Sudan.

INNUMBERS

2011 South Sudan gained independence from Sudan on July 9.

11 million Estimated South Sudanese citizens in need of humanitarian assistanc2e.

$1,600 Real gross domestic product per capita (2017).

On Friday, the price of South Sudan’s oil exports fell from $100 per barrel to $70. Michael Makuei, the country’s information minister, accused oil companies of exploiting the crisis to drive down prices. Experts say the situation in Sudan could have long-term implications for South Sudan’s oil industry.

“The situation is alarming, as any spillover from Sudan will be a very big issue for us here and this is why President Salva Kiir has been calling for a ceasefire so that normalcy returns to Sudan,” Deng Dau Deng Malek, acting minister of foreign affairs, told Arab News.

“South Sudan is very concerned about the situation in Sudan, especially given our shared border and historical ties. Any escalation of conflict in Sudan could have serious consequences for our country.”

Maj. Gen. Charles Machieng Kuol, a senior military officer in South Sudan, also weighed in on the potential harm that a prolonged conflict might cause, emphasizing the need for stability in the region.

“We have forces which have been deployed along the borders before,” he told Arab News. “Our country is preparing now to protect the borderlines, as we don’t want this war to escalate to our country.”

Sudan has lived through multiple civil wars since gaining independence from Britain and Egypt in 1956.

Its first north-south civil war broke out several months before independence on Jan. 1, 1956 and lasted until 1972. It pitted successive governments in the Muslim-dominated north against separatist rebels in the predominantly Christian south.

The 17-year conflict ended with a treaty under which the south was granted autonomy. However, the agreement collapsed in 1983 after 11 years of relative peace when President Jaafar Nimeiri decided to revoke the south’s autonomous status.

Sudan’s second civil war erupted in 1983 following an uprising by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army led by John Garang. In 1989, Omar Al-Bashir took power in a coup and cracked down on the southern rebellion.

Omar al-Bashir, Sudan's former ruler, waves a walking stick during a visit in Nyala, the capital of South Darfur province on September 21, 2017. He was accompanied by paramilitary commander Mohamed Hamdan Daglo (L). (AFP File)

he war ended on Jan. 9, 2005, when Garang signed a peace accord with Al-Bashir’s government. The cornerstone of the accord was a protocol granting it six years of self-rule ahead of a 2011 referendum on whether to remain part of Sudan or secede.

South Sudan proclaimed independence on July 9, 2011, splitting Africa’s biggest country in two. As South Sudan separated, conflict resumed in the Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile in the rump state of Sudan in areas held by former guerrillas, now called the SPLM-North.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

The presence of these former South Sudanese rebels close to the shared border complicates the current crisis, as they could easily be dragged into the conflict.

Manasseh Zindo, an independent analyst from South Sudan and a former delegate to the South Sudan peace process, says the involvement of these rebel leaders could have catastrophic implications for the security of South Sudan.

“Malik Agar is the leader of the SPLM-North. He is from the Blue Nile State near the Nuba Mountains in Sudan. He was part of South Sudan during the liberation struggle,” Zindo told Arab News.

“After the secession of South Sudan, the boundary delineation put him in Sudan. He is now part of the sovereign government in Khartoum. If he takes sides in the current conflict in Sudan, it could spill into South Sudan because of his links with South Sudan.”

Gen. Simon Gatwech Dual and Gen. Johnson Olony, two South Sudanese military officials who have shifted allegiance between different factions, are also based close to the Sudanese border.

Both men are leaders of SPLM-IO Kitgwang, a faction that broke away from Riek Machar’s SPLM-IO.

Rebels of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO), a South Sudanese anti-government force, patrol in their base in Panyume, on the South Sudanese side of the border with Uganda. (AFP File)

“If Gen. Simon or Gen. Johnson can be dragged into the Sudanese conflict, it can spill into South Sudan with catastrophic implications for the security of South Sudan,” said Zindo.

The South Sudanese government is now on high alert and has urged citizens living close to the border to be vigilant and report any suspicious activities. It has also called for a peaceful resolution of the conflict in Sudan, adding that it is willing to play the role of mediator if both parties agree.

“The president (Salva Kiir) has been calling for a ceasefire and the cessation of hostilities for humanitarian assistance to reach the needy,” said Deng Malek, the acting minister of foreign affairs.

“He talked directly to President Al-Burhan and Deputy President Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo a number of times to appeal to them so that they observe the cessation of hostilities and return to the negotiation table.”

In this picture taken on August 17, 2019, South Sudan President Salva Kiir Mayardit is seated next to

General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan (front left) during a ceremony to sign an agreement paving the way for a transition to civilian rule. Kiir has appealed to Al-Burhan and rival general Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo to stop fighting and resolve their problems peacefully. (AFP)

The UN and other international bodies have also expressed concern about the situation in Sudan and its potential impact on South Sudan. The UN refugee agency, UNHCR, says the conflict in Sudan has already forced thousands of people to flee into South Sudan, exacerbating an already dire humanitarian situation.

South Sudan is still recovering from a six-year civil war that ended in 2018, which left more than 380,000 people dead and displaced millions. The country is now trying to implement a peace agreement that was signed in September 2018, but progress has been slow, with sporadic clashes reported in different parts of the country.

As the situation deteriorates, Sudanese refugees are flooding across the border into South Sudan. International aid agencies are calling for urgent action to prevent a humanitarian catastrophe.

According to UNHCR, there are currently more than 800,000 South Sudanese refugees in Sudan, a quarter of whom are in Khartoum and directly impacted by the fighting.

Egypt, Sudan’s northern neighbor, said on Thursday that at least 14,000 Sudanese refugees had crossed its border since the fighting erupted, as well as 2,000 people from 50 other countries.

At least 20,000 people have escaped into Chad, 4,000 into South Sudan, 3,500 into Ethiopia and 3,000 into the Central African Republic, according to the UN, which warns that if the fighting continues as many as 270,000 people could flee.

Gavin Kelleher, a humanitarian analyst for the Norwegian Refugee Council in South Sudan, said that the country is ill-prepared to absorb the expected influx from the north.

“The number of new arrivals is still unclear, but they are very likely to continue to increase in the coming weeks and it’s really important that we put the wheels in motion now for an effective humanitarian response,” Kelleher told Arab News.

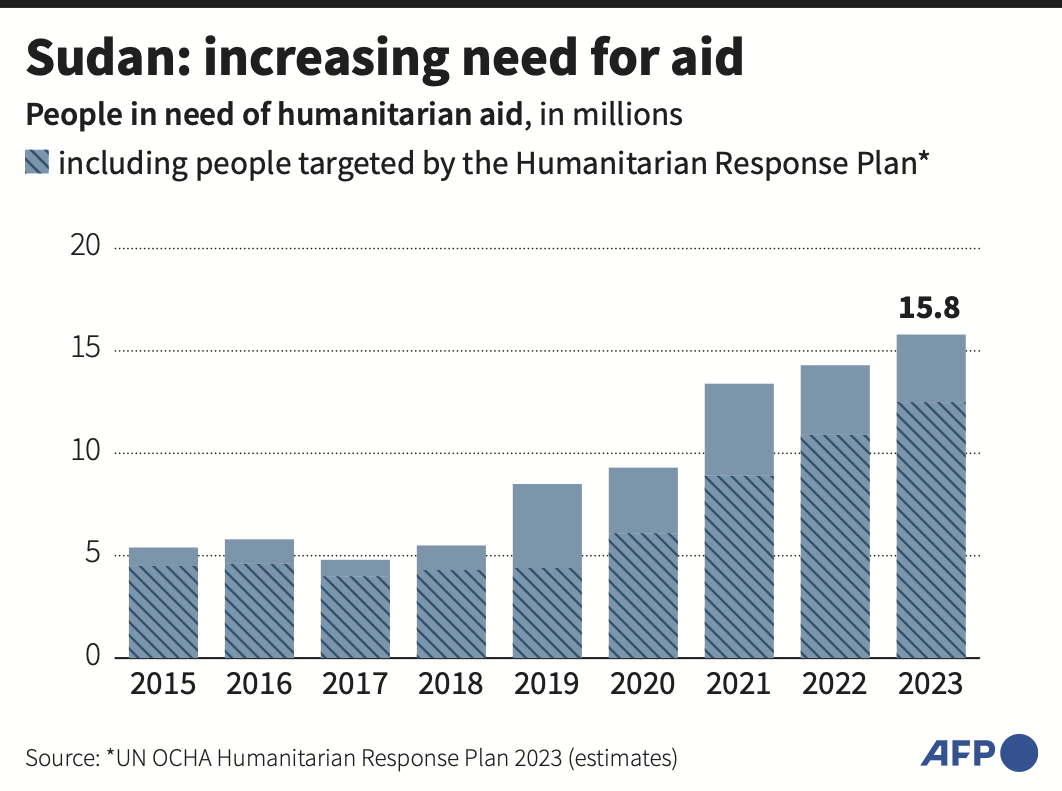

“About 75 percent of South Sudan’s population are assessed to be in need of humanitarian assistance already, and the majority of the country has emergency or critical levels of food insecurity.

“Further shocks such as waves of new arrivals from Sudan are stretching the limited amount of resources available to new levels.”