MASKWACIS, Canada: Pope Francis on Monday apologized for the “evil” inflicted on the Indigenous peoples of Canada on the first day of a visit focused on addressing decades of abuse at Catholic-run residential schools.

The plea for forgiveness from the leader of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics was met with applause by a crowd of First Nations, Metis and Inuit people in Maskwacis, in western Alberta province — some of whom were taken from their families as children in what has been branded a “cultural genocide.”

“I am sorry,” said the 85-year-old pontiff, who remained seated as he delivered his address at the site of one of the largest of Canada’s infamous residential schools, where Indigenous children were sent as part of a policy of forced assimilation.

“I humbly beg forgiveness for the evil committed by so many Christians against the Indigenous peoples,” said the pope, citing “cultural destruction” and the “physical, verbal, psychological and spiritual abuse” of children over the course of decades.

Francis spoke of his “deep sense of pain and remorse” as he formally acknowledged that “many members of the Church” had cooperated in the abusive system.

Francis spoke of his “deep sense of pain and remorse” as he formally acknowledged that “many members of the Church” had cooperated in the abusive system.

As he spoke, the emotion was palpable in Maskwacis, an Indigenous community south of provincial capital Edmonton that was the site of the Ermineskin residential school until it closed in 1975.

Several hundred people, many in traditional clothing, were in attendance, along with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Mary Simon, the country’s first Indigenous governor general.

Many lowered their eyes, wiped away tears or leaned on and hugged neighbors, and Indigenous leaders afterwards placed a traditional feathered headdress on the pope.

Counsellors were waiting to provide support to those who may need it, and volunteers had earlier distributed small paper bags for the “collection of tears.”

“The First Nation believes that if you cry, you cry love, you catch the tears on a piece of paper and put it back in this bag,” explained Andre Carrier of the Manitoba Metis Federation.

Later the bags will be burned with a special prayer, “to return the tears of love to the creator,” he said.

From the late 1800s to the 1990s, Canada’s government sent about 150,000 children into 139 residential schools run by the Church, where they were cut off from their families, language and culture.

Many were physically and sexually abused, and thousands are believed to have died of disease, malnutrition or neglect.

During a ceremony performed before the pope spoke in Maskwacis, Indigenous people carried a bright red 50-meter-long banner on which the names — or sometimes only the nicknames — of all the children known to have died were written in white. There were 4,120 of them, officials said.

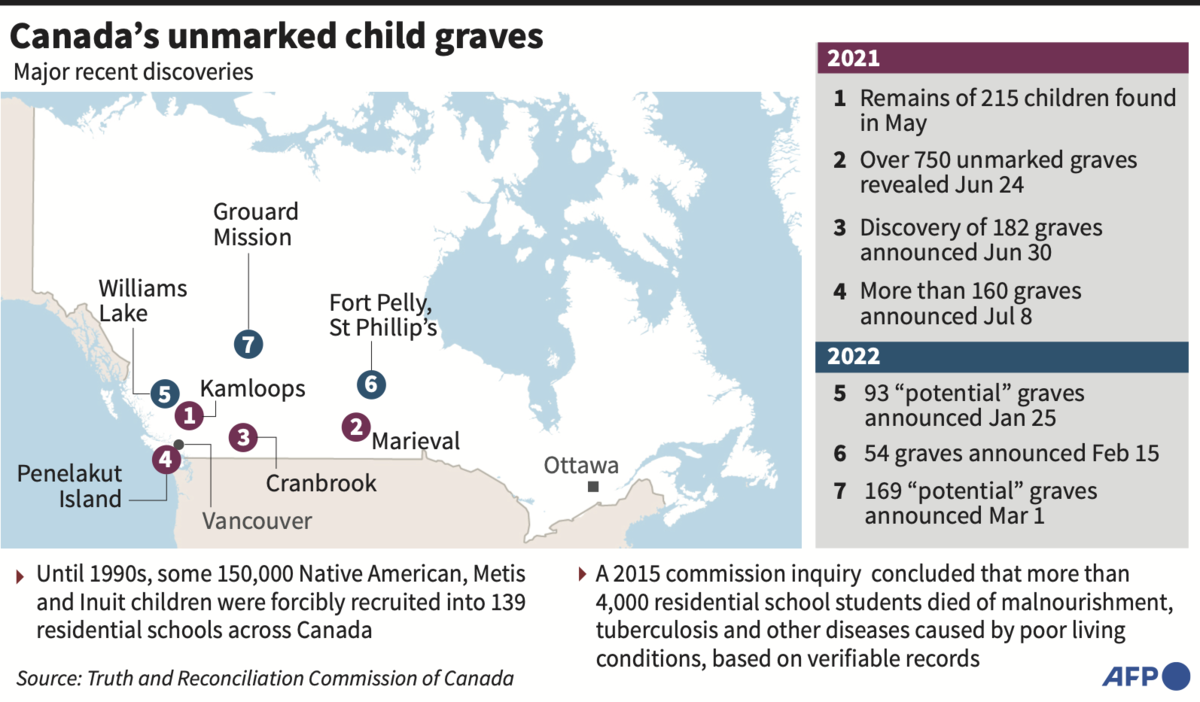

Since May 2021, more than 1,300 unmarked graves have been discovered at the sites of the former schools, sending shockwaves throughout Canada — which has slowly begun to acknowledge this long, dark chapter in its history.

A delegation of Indigenous peoples traveled to the Vatican in April and met the pope — a precursor to Francis’ trip — after which he formally apologized.

But doing so again on Canadian soil was of huge significance to survivors and their families.

Later in the day, Francis traveled to the Sacred Heart Catholic Church of the First Peoples in Edmonton, one of the city’s oldest churches, for a second speech.

“I can only imagine the effort it must take... even to think about reconciliation,” he said.

“Nothing can ever take away the violation of dignity, the experience of evil, the betrayal of trust. Or take away our own shame, as believers.”

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who was also at the Maskwacis ceremony, said that “reconciliation is the responsibility of all Canadians.”

“No one must ever forget what happened at residential schools across Canada and we must all ensure it never happens again,” he said in a statement.The flight to Edmonton was the longest since 2019 for Francis, who has been suffering from knee pain and was forced to use a wheelchair on the Canada trip.

His frailty was apparent during the visit to the Sacred Heart, as — using a cane — he moved slowly across the dais to bless a statue, before returning to his wheelchair to leave the church.

The papal visit is also a source of controversy for some.

“It means a lot to me” that he came, said Deborah Greyeyes, 71, a member of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, the largest Indigenous group in Canada.

“I think we have to forgive, too, at some point,” she told AFP. But “a lot of stuff was taken away from us.”

After a mass before tens of thousands of faithful in Edmonton on Tuesday, Francis will head northwest to an important pilgrimage site, the Lac Sainte Anne.

Following a July 27-29 visit to Quebec City, he will end his trip in Iqaluit, capital of the northern territory of Nunavut and home to the largest Inuit population in Canada, where he will meet again with former residential school students, before returning to Italy.