KARACHI: When Shahida Kazi got her first job as a reporter, she quickly earned an unpleasant nickname: “Meena Bazaar Reporter,” the Urdu word for funfair that some of her colleagues and friends used to mock her ambition to become a serious journalist.

The nickname didn’t stick. That job, as a reporter at the Dawn newspaper in Karachi, made Kazi Pakistan's first female correspondent and launched a career that spanned decades in both print and television journalism and which involved assignments that saw her cover everything from visits by foreign dignitaries to historic political rallies and devastating natural disasters.

The job offer came in 1966, from a city editor at Dawn who had read freelance articles Kazi had penned as a postgraduate student at the University of Karachi. She was stunned at the offer: at the time, reporting, which involved fieldwork, was widely seen as a profession unsuited to women.

But Kazi proved everyone wrong.

She was born in 1944 into a family that encouraged women’s education. But while most of her female cousins went into medicine, Kazi took an interest in English literature and ultimately applied to the newly established department of journalism at the University of Karachi. When she enrolled there in 1963, she realized she was the country’s first and only woman student of journalism.

An undated photo of Shahida Kazi, Pakistan's first female reporter, during her student days at the Karachi University. (Photo courtesy: Shahida Kazi)

Before venturing into reporting, Kazi’s father had pushed her to sit the Central Superior Services (CSS) examination and join the federal bureaucracy. However, she decided not to pursue the civil services as a profession since women at the time were not allowed positions in prestigious sectors like the foreign service and district management group.

“I decided this [journalism] was what I wanted to do,” she told Arab News in an interview last week.

Her first assignment was an interesting one.

“The king of Afghanistan [Zahir Shah] was visiting Pakistan along with his wife and daughter,” Kazi recalled. “On my very first day at work, I was sent to cover the activities of the queen and the princess.”

Another memorable assignment, Kazi said, was covering the death and funeral of Fatima Jinnah, the sister of Pakistan’s founding father.

“It was a great front page story,” she said. “When Shireen Bai, Fatima Jinnah’s sister, arrived from India, I was the first person who interviewed her.”

That story was also a first lesson in censorship.

Many at the time believed that Jinnah’s death in July 1967 involved foul play, particularly as she was a prominent politician in her own right who had contested an election against Pakistan’s first military ruler, General Ayub Khan. Jinnah had also been critical of previous governments and her speeches were either not broadcast or heavily censored by state media.

“All of us knew that Fatima Jinnah’s death was not normal ... though nobody said that." Kazi said. "Even the newspapers were silent. If I had written that she was murdered, the editorial board would have cut it out.”

After about two years of reporting for Dawn, Kazi joined state-run Pakistan Television (PTV) where she spent the next two decades, and where her performance and output landed her the job of news editor, a position previously never held by a woman.

“My job was to supervise cameramen and editors,” Kazi said. “I also wrote commentaries for films.”

During her stay with PTV, she witnessed many historic developments, cycles of political instability, military coups, the 1971 war and the creation of Bangladesh from what was previously East Pakistan.

“I was witness to all these things,” she said. “I saw how governments controlled the media.”

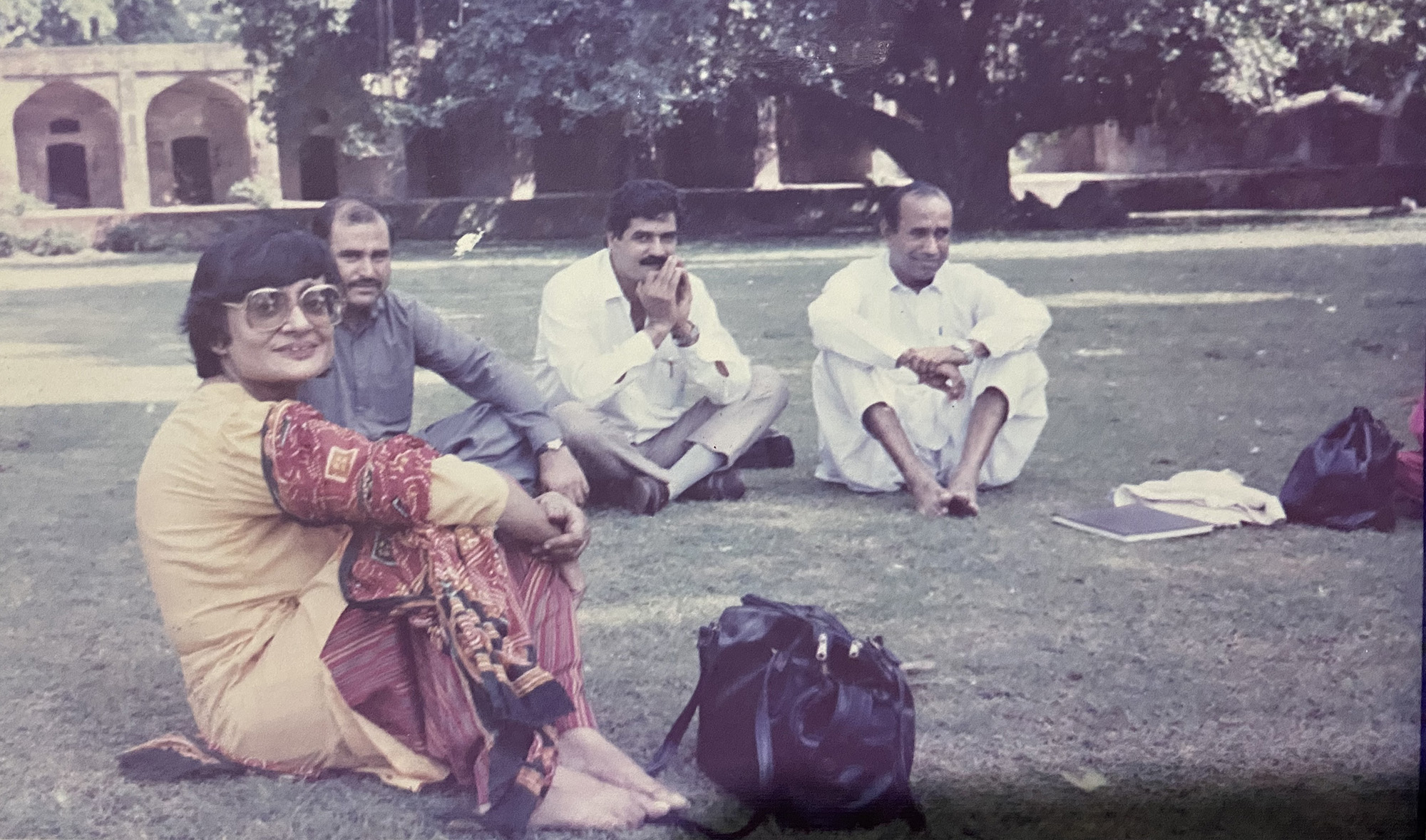

In this undated photo, Shahida Kazi, Pakistan's first female reporter, can be seen with her friends at the Karachi University. (Photo courtesy: Shahida Kazi)

Asked if she had faced gender discrimination during her career, she said there was “no glass ceiling” for her since she was promoted on several occasions over male colleagues purely on the basis of merit.

“I always believe that women should not feel like victims,” Kazi said. “They should make themselves known by their hard work.”

Describing herself as a feminist, Kazi said women’s rights movements in the past, and Aurat March today, had been misinterpreted in Pakistan.

“Women are doing something very good,” she said. “They are fighting for their rights. But some people are taking it the wrong way.

"Women have the right to not be harassed at the workplace. Women have the right of not being attacked while going anywhere. Women have the right of not being killed for honor. Women have the right not to be beaten by their husbands.”

“When I call myself a feminist,” she said, smiling, “I don’t mean that I hate men.”

After a little pause, Kazi added: “I sometimes feel that I really did something for the cause of women empowerment in Pakistan since women were completely neglected in the newspaper business before me.”