DUBAI: Embedded in rich history, Arabic calligraphy has been classified into six essential proportioned scripts (or pens), set by the renowned Abbasid polymath and vizier Ibn Muqla, who was born in Baghdad in 885/6.

One particular script that the Persian master calligrapher invented and refined remains the most challenging, as it requires a calligrapher to execute it with dedication, patience and an eye for detail: The Thuluth script.

To many, this stately form of writing is so crucial that it acts like a test, defining whether or not a calligrapher is a true master of his or her craft.

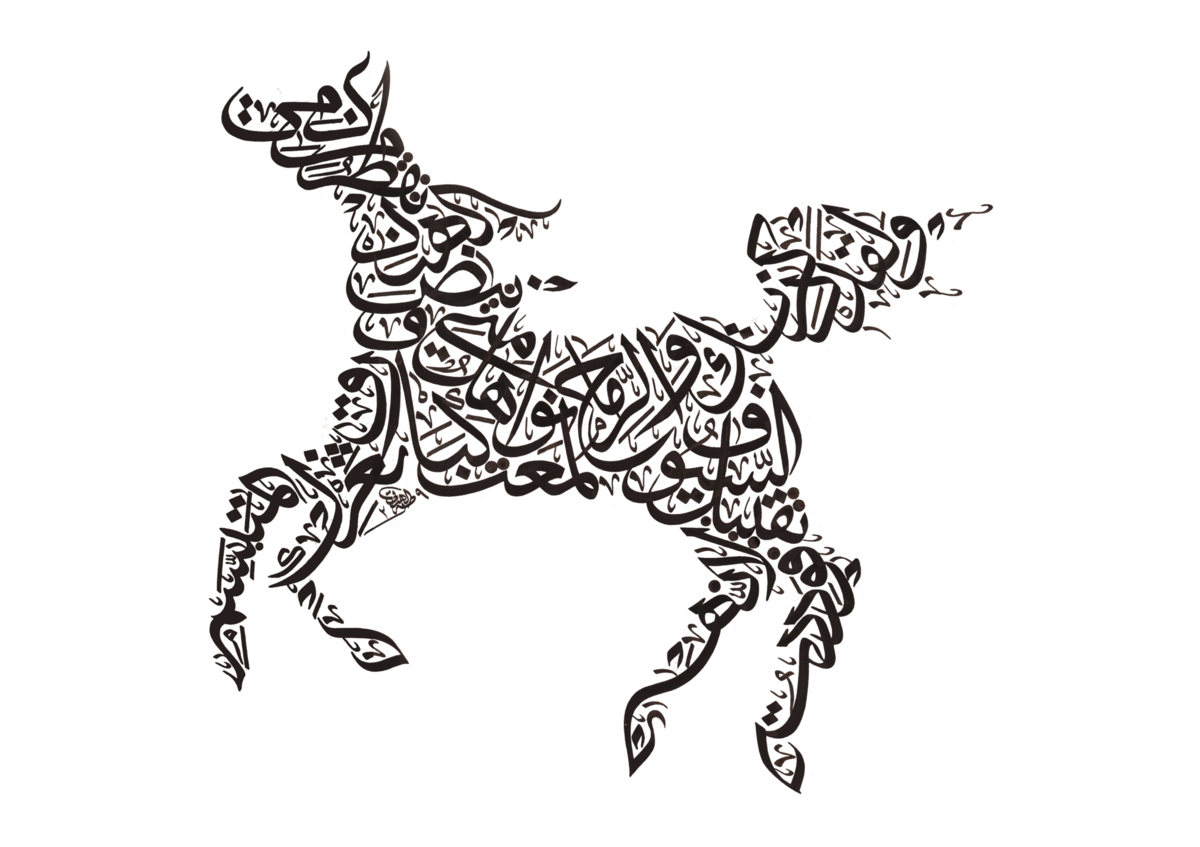

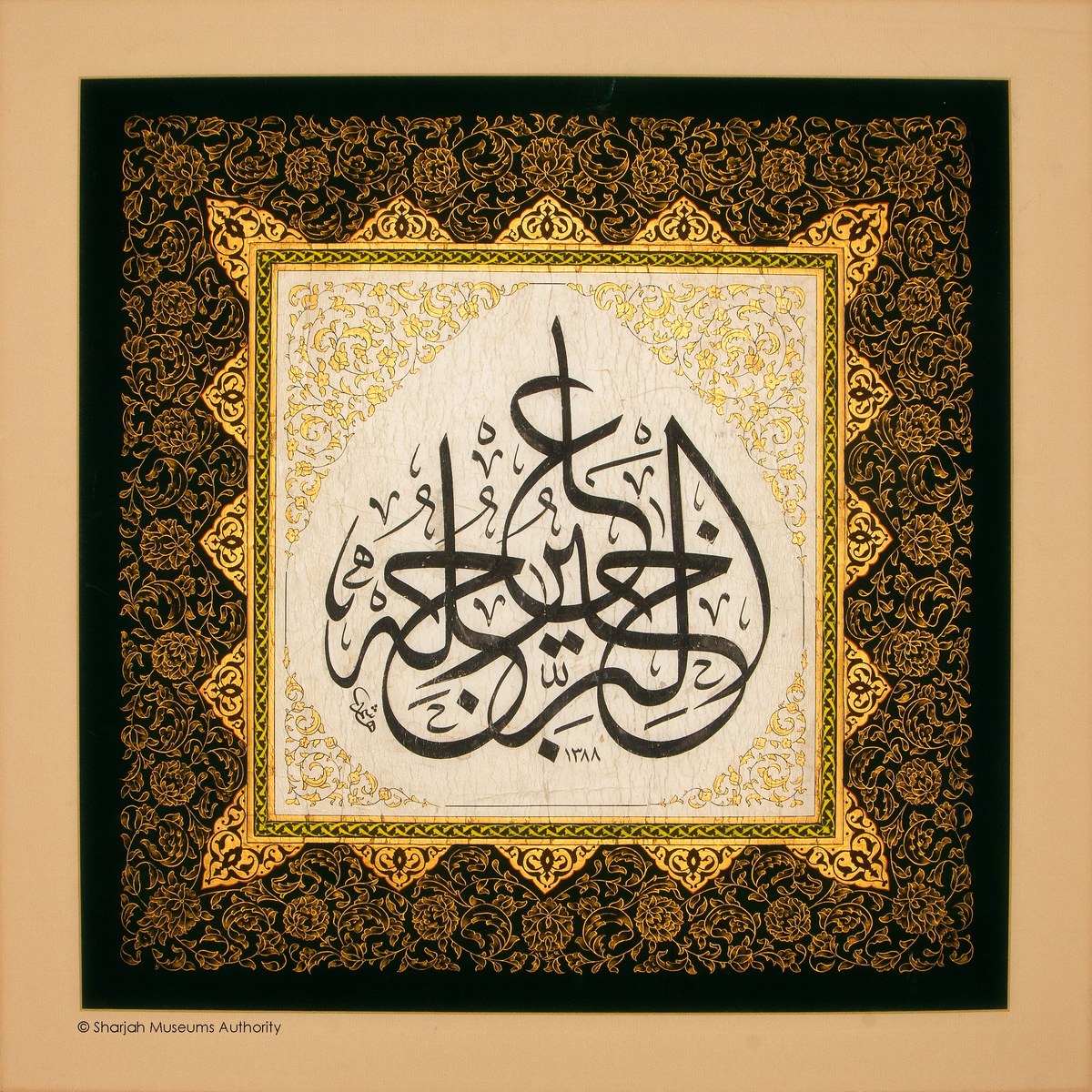

Calligraphy artist Taha Al-Hiti created this artwork. (Supplied)

“In Arabic calligraphy, the Thuluth script is the mother of scripts because it has been encountered by many calligraphers,” Saudi artist Abdulaziz Al-Rashidi, who has studied and practiced this form of writing since his childhood in the 1980s, told Arab News.

“A calligrapher can’t be recognized as one if he can’t perfect the Thuluth script, as it’s the hardest.”

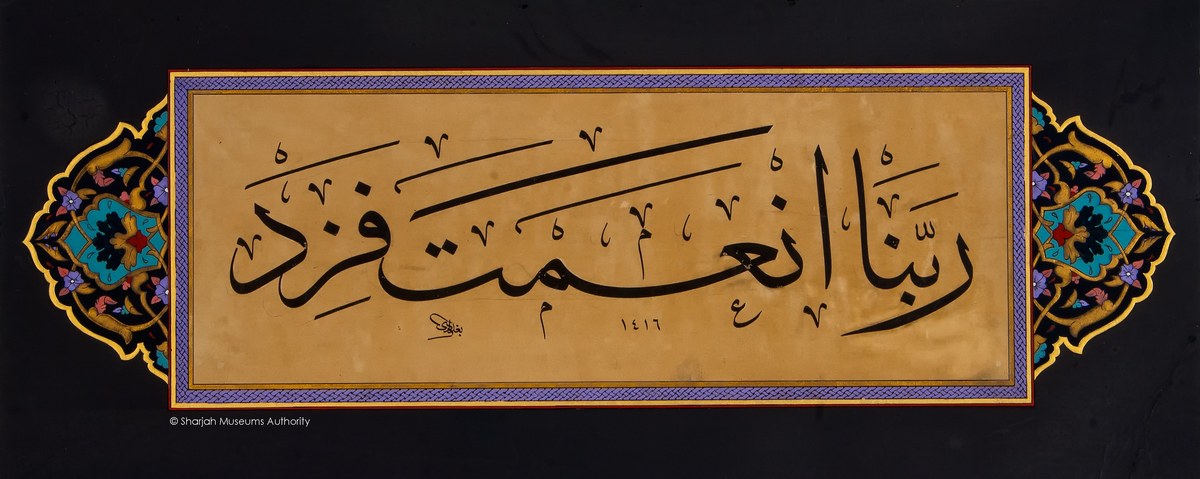

To many, Thuluth is so crucial that it acts like a test, defining whether or not a calligrapher is a true master of his or her craft. (Supplied)

In terms of aesthetics, Thuluth — dating back to the days of the Ummayad Caliphate in the seventh century — is noticeably cursive, exuding a visually sophisticated and complex flow of interlacing letters and barbed heads, studded with diacritics (or harakat).

Al-Rashidi said their presence in Thuluth is important as they partly contribute to the overall beauty of this script.

This artwork is by calligraphy artist Taha Al-Hiti. (Supplied)

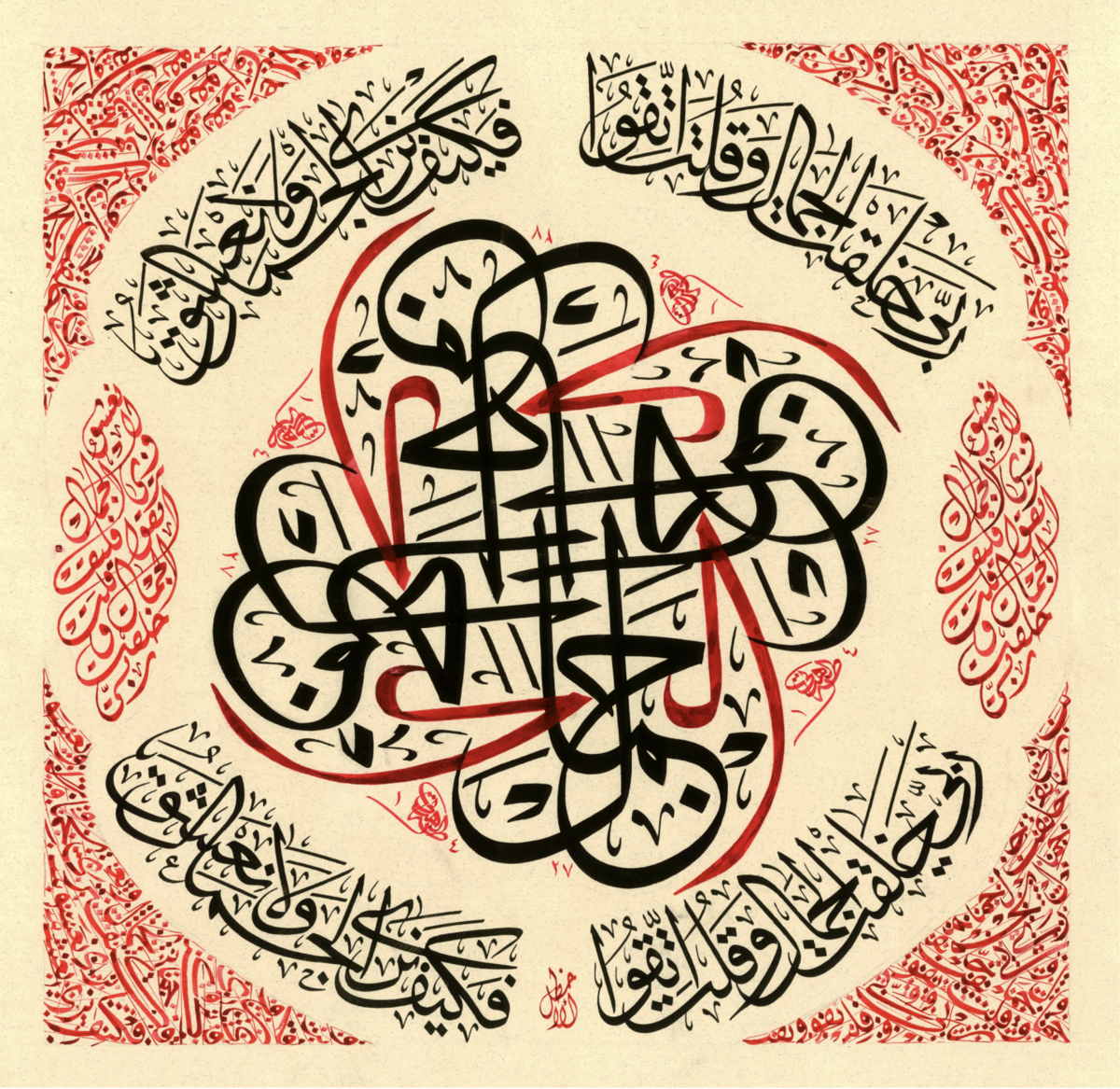

Dr. Tanja Tolar, who teaches the history of Arab painting and mosaics at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), told Arab News “This is a large script, free-flowing and smoother. If Kufic (script) impresses with elegance of proportions and obedience to strict rules, Thuluth allows for more playfulness.”

She added: “That said, there are still rules a calligrapher needs to follow in order to produce Thuluth script, but the hand moves more freely and in a variety of forms, not necessarily just in a vertical line. This is particularly true for contemporary calligraphy that uses Thuluth as an expression of artistic form — for example, the text is written in Thuluth script but in the shape of an animal or person.”

Keramat Fathinia, who conducts a calligraphy course at SOAS, told Arab News that Thuluth is uniquely characterized by its “legibility, spacing and diacritical signs, which have made this script to be read and written in a faster pace.”

This piece is by calligraphy artist Taha Al-Hiti. (Supplied)

He also brought to attention the important element of the vivid “rhombic (diamond-shaped) dot,” a unit of measurement devised by Ibn Muqla to achieve proportionality.

“Thick dots with better contrast in Thuluth facilitated the process of reading and writing much better than a combination of green, blue and yellow dots in Kufic,” said Fathinia.

In Arabic, the term “thuluth” means “one third,” and this versatile meaning is particularly manifested in the overall aesthetics of this type of script.

Tolar said: “Thuluth is distinguished by its large letters that slope. It’s believed that one-third of the letter will slope.”

Taha Al-Hiti, who created this artwork, is a graduate of architecture from the University of Baghdad in Iraq. (Supplied)

Researchers have also made the case that “one third” could possibly refer to its pen size compared to the larger Tumar pen that was mostly utilized by sultans and caliphs signing official decrees and correspondence.

Unlike the angular and older Kufic script, Thuluth was rarely used for writing Qur’anic texts, but was actually commonly utilized for grand architectural settings, tombstones, manuscripts, ceramics and metalwork.

“The aesthetics of the large, sloping and soft Thuluth has been also used for inscriptions on objects, such as enameled and gilded glass mosque lamps produced during the Mamluk period in 14th-century Syria and Egypt,” Tolar said.

In Arabic, the term “thuluth” means “one third.” (Supplied)

Al-Rashidi said: “There’s a holiness to the Thuluth script. If you look at some mosques, such as Masjid Al-Haram, you’ll find the Kaaba inscribed with Thuluth writing.”

Following this line of thought, this powerful script usually appears in the context of elaborate, religious headings and inscriptions, adorning the walls, niches, minarets and domes of iconic monuments in the wider region, including Agra’s Taj Mahal, Aleppo’s Ummayad Mosque and the Shah Mosque in Isfahan.

In the case of the Taj Mahal, its exterior white marble panels read Qur’anic verses that were beautifully inscribed by the 17th-century calligrapher Amanat Khan.

With an element of show and prestige, the Thuluth script, which remains popular to this day, is considered by experts as one of the most ornamental forms of Arabic writing.

Thuluth dates back to the days of the Ummayad Caliphate in the seventh century. (Supplied)

In many instances, a Thuluth-designed body of text is accompanied by delicate and repetitive floral elements, beautifying the overall composition.

We can, for instance, sense this in a majestic pierced steel plaque — housed at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto — of which the name of the Prophet Mohammed’s daughter Fatima Al-Zahra (Fatima the Radiant) has been written in large and elegant letters, surrounded by ornamental intricacies.

Created in Iran in the late 1600s, this work of art was likely designed for a shrine door or an embellished frieze.