After radical clerics hijacked the protests, the Islamic Republic launched a campaign to destabilize the region that continues to this day

Summary

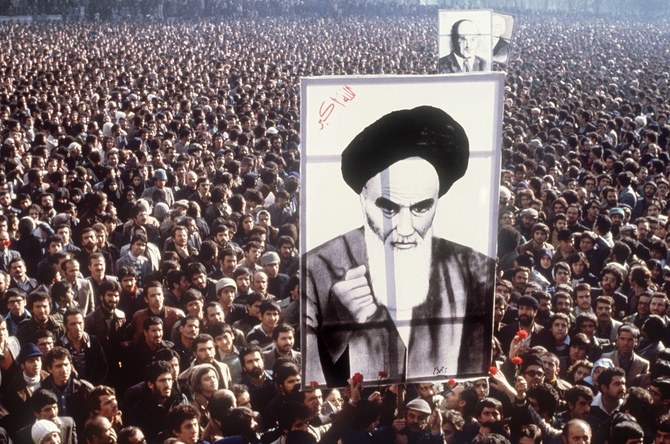

On Feb. 11, 1979, an Islamic revolution changed Iran from a pro-Western monarchy into an anti-Western theocracy. Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi had always relied on Western support, but many Iranians chafed at his rapid program of westernization. The first demonstrations erupted toward the end of 1977, and over the following 14 months the slow-motion collapse of the shah’s authority culminated in his overthrow and the return from exile of Shiite religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini.

Key Dates

-

1

Demonstrations and riots erupt in cities across Iran, triggering months of increasingly violent protests.

-

2

More than 80 are killed and hundreds injured in Tehran when security forces open fire on demonstrators in Jaleh Square on a day remembered as Black Friday.

-

3

Ayatollah Khomeini, in exile in France, orchestrates the Muharram protests, bringing millions onto the streets calling for the shah’s removal and Khomeini’s return.

-

4

The shah and his family flee Iran, never to return.

-

5

Khomeini returns to a rapturous welcome from millions of supporters and, days later, appoints an interim revolutionary government.

-

6

The military lays down its arms and the government of Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar, appointed by the shah, collapses. Bakhtiar, who attempts to organise a counter-coup from exile in France, is later assassinated.

-

7

Angered by Washington’s refusal to return the shah for trial from the US, where he is receiving treatment for cancer, revolutionaries seize the US Embassy in Tehran and hold 52 Americans hostage for 444 days.

The most immediate consequence was the seizure of the US Embassy in Tehran by revolutionary students, who held 52 Americans hostage for 444 days. But in the long term, the revolution turned a close ally of Washington into its sworn enemy, triggering a bitter enmity with consequences for the region that echo to this day.

LOS ANGELES: The year 1979 is one of the most pivotal in modern history due to the Islamic revolution in Iran, an event that reverberated beyond the country’s borders and fundamentally altered the Middle East’s political landscape, affecting geopolitical alignments four decades later.

Since some politicians and policy analysts continue to misunderstand the Islamic Revolution or underestimate the commitment of the Islamic Republic to exporting its revolutionary ideals, it is critical to shed light on the underlying causes and the long-term impact it has had domestically, regionally and globally.

Before the revolution, most Iranian people were struggling to set up a representative and democratic system of governance. They were dissatisfied with Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi due to the widespread political and financial corruption and human-rights violations. Many people in Iran were also discontent with American foreign policy because of the 1953 coup when the Eisenhower administration and UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to overthrow the first democratically elected government in Iran, which was led by nationalist Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddegh, and reinstate the shah, who had built a close alliance with Washington and the West.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini took advantage of this situation and capitalized on the people’s grievances to seize power. In 1978, periodic demonstrations and protests began to erupt as ordinary people and various oppositional groups — including the Marxists, modernist Islamists, religious fundamentalists, constitutionalist liberals, leftists and reformists — came together. But the international community did not believe that these protests could result in the revolution of 1979. This is more likely due to the fact that the shah was successful in creating a desirable image of himself outside Iran as a king who enjoyed legitimacy and the support of the Iranian people.

Khomeini’s party had an edge over other political parties because the shah, like many others at this time, did not view the clerics as a threat. Instead, he invested significant political capital in cracking down on other political institutions, such as the nationalists, Marxists and leftists. This allowed Khomeini’s party to thrive, and it became one of the most powerful and best organized groups in the country. It could operate through enormous networks such as mosques and religious organizations.

Ultimately, Khomeini’s fundamentalist organization co-opted the revolution in February 1979. After the shah fled the country, the vast majority of Iranians voted for the Islamic Republic because they did not conceive that Khomeini’s religious party would be capable of committing the atrocities it ultimately came to carry out, or that it would have such an unrelenting hunger for power. Instead, the country thought it was on a smooth path toward democracy, with no expectation of returning to the shah’s era.

Once the clerics had hijacked the revolution, their key objective became the consolidation of power. This was fulfilled primarily through two important landscapes: The hostage crisis and the brutal crackdown on the Iranian population. This revealed the regime’s determination to show to its own people that it was not afraid of shedding blood in order to achieve its objectives.

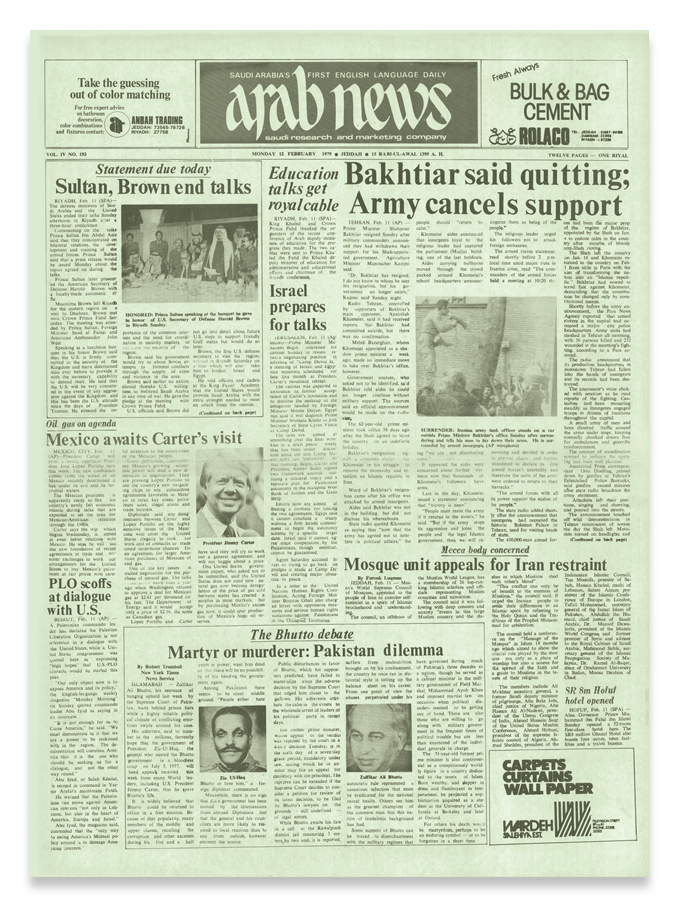

“Makkah’s World Supreme Council of Mosques appealed to the people of Iran to exercise self-restraint in a spirit of Islamic brother and understanding.”

Farouq Luqman on the front page of Arab News, Feb. 12, 1979

Thousands upon thousands of people from other political or religious parties were ultimately tortured and executed. The regime established dozens of “death commissions,” which were run by people such as Ebrahim Raisi, who later ran for president, and Mostafa Pourmohammadi, who was served as minister of justice under President Hassan Rouhani. According to human rights groups, the death commissions were major players in the execution of some 30,000 political prisoners in a four-month period in 1988. Those killed were accused of having loyalties to anti-theocratic resistance groups, mainly the People’s Mujahedin of Iran.

The Islamic Republic also broke international laws by instigating the 1979 hostage crisis, in which 52 Americans were detained and humiliated for 444 days. This was a turning point in US-Iran relations and it empowered Iran’s hard-liners, ultra-conservatives and Principlists. It gave them the platform to further consolidate their power, crush the remaining leftists, liberals and secular groups inside the country, and present to the world the Islamic Republic’s defiant and revolutionary nature.

Tehran’s regional policies became anchored in exporting its revolution to other nations; increasing its influence through military adventurism; asymmetrical warfare; pursuing a sectarian agenda by inciting Shiites against Sunnis; the sponsorship of proxies and terror groups from Yemen to Iraq; and thwarting the objectives of other regional powers, particularly Saudi Arabia. Tensions in the region intensified as a belligerent, assertive and revolutionary dimension was added to Tehran’s foreign and regional policies.

A page from the Arab News archive from Feb. 11, 1979.

Finally, the Islamic Republic not only vied for regional dominance, but also absolute exertion of leadership in the Muslim world. And, since Saudi Arabia is considered a critical regional power, the cradle of Islam and home to its two holiest cities, Makkah and Madinah, Tehran became determined to undermine the Kingdom’s national, geopolitical and strategic interests in the region. As a result, antagonism toward Saudi Arabia became one of the core pillars of the mullahs’ regional policy.

- Dr. Majid Rafizadeh, an Iranian-American political scientist who is a columnist for Arab News, was born in Iran a year after the revolution. Several of his family members, including his father, were tortured by the regime for criticizing the ruling mullahs. Twitter: @Dr_Rafizadeh