LONDON: With the elimination on Jan. 3 of Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian general who oversaw the Islamic Republic’s web of regional proxy armies, attention is bound to turn sooner or later to Hezbollah, the Lebanese armed group whose cloak-and-dagger operations have been detected in places as far apart as South America and Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

Entrenched deeply over the years in South America, Hezbollah is arguably the only Shiite militia belonging to the Soleimani network that has the twin advantages of ability and proximity to consider retaliating against the Trump administration for the targeted killing of the Quds Force commander with a direct attack on the US.

As recently as September, authorities in New York apprehended Alexei Saab, aka Ali Hassan Saab, an alleged Hezbollah operative who “conducted surveillance of possible target locations in order to help the foreign terrorist organization prepare for potential future attacks against the United States.”

Unlike China and Russia, the US is an avowed enemy of Hezbollah, having long designated the entire group, including its political wing, as a foreign terrorist organization.

In recent months, the State Department and Washington’s intelligence community have concluded that there is enough evidence to support claims linking Hezbollah to criminal activities, including drug trafficking, in South America and Europe.

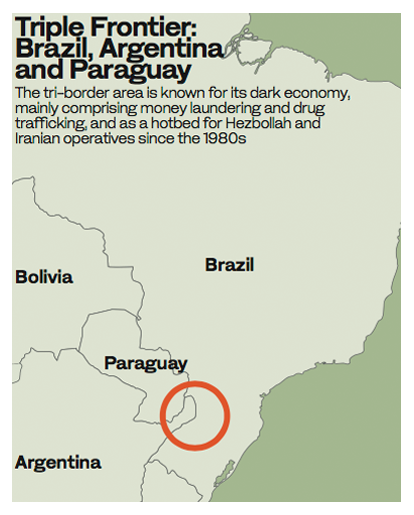

Much has been written about Hezbollah’s presence in the “triple frontier” area along the Paraguay-Argentina-Brazil border in South America. Since the Al-Qaeda attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Americans have warned of potential terrorist cells forming in this under-policed corner of the continent.

Hezbollah has been able to find a footing in the tri-border area by piggybacking on the Lebanese diaspora presence. The ancestors of South Americans of Lebanese descent began arriving in the area before 1930 and were mostly Christian.

The fact that, today, more than 5 million Lebanese migrants and their descendants live in just two countries (Brazil and Argentina) has proved a distinct advantage for Hezbollah, which tries to cultivate intelligence assets from across the religious spectrum.

Hezbollah has developed local contacts to facilitate as well as conceal its drug-trafficking, money-laundering and terrorist-financing operations. Since 2009, a number of Lebanese nationals have been sanctioned by the US Treasury for their connection to organized crime, involving drug trafficking and money laundering in particular.

Just last month, the US Department of Justice sentenced Lebanon-born Ali Kourani, a naturalized US citizen, to 40 years in prison for his “illicit work” as an operative for ”the Islamic Jihad Organization,” the “external attack-planning component” of Hezbollah.

Maximilian Brenner, of the Berlin-based Security Institute, sees a mixed picture emerging from recent developments. “In the US, significant progress has been made in terms of harnessing crime-fighting ops to curb Hezbollah,” Brenner said.

“However, the international community is divided on the issue, with diverging interests preventing organized action to tackle Hezbollah also in the criminal — not solely in the international terrorism — context.”

Jonathan Cardozo, of the Paris-based Media Research Inc., says there is obvious overlap between terrorism and illicit drug trade, but the motives are not necessarily the same.

“Americans will find it very difficult, if not impossible, to combine the war against terrorism with the war against the drug trade, especially considering the differences in agency infrastructure, personnel and local assets,” he said.

“Slow-moving bureaucracies are not equipped to fight guerrilla-style tactics of lawless — and ruthless — criminal and terrorist outfits. While terrorists and criminals certainly collaborate in many instances, it is incredibly difficult to pinpoint any grand strategy at play in Latin America between the two elements.”

What is for certain, though, is that the rationale behind Hezbollah’s “South America strategy” is closely linked to its origin as revolutionary Iran’s most successful export.

Even as Hezbollah’s domestic position was fortified by election successes and sectarian polarization, its aggressive anti-Western rhetoric and targeting of US and Israeli interests placed it firmly in the crosshairs of the two countries. On the other hand, distant South America, with its leftist political parties and “revolutionary” regimes, was a study in friendliness.

Sympathetic South American governments granted Hezbollah a high degree of operational freedom. For instance, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the socialist politician who served as Brazil’s president between 2003 and 2010, invested a lot of diplomatic capital in trying to forge a rapprochement with Hamas and Hezbollah as well as the two groups’ main backer, Iran.

Da Silva’s initiative was part of a larger strategy of increasing Brazil’s outreach to, and strengthening bilateral relations with, Russia and Iran and their Middle Eastern allies, while effectively ignoring Washington’s concerns regarding the presence of Hezbollah cells in his country.

According to Ghanem Nuseibeh, founder of strategy and management consultancy company Cornerstone Global Associates, Hezbollah has been active in Latin America for decades now.

The monument at the meeting point of Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay. (AFP)

“The organization has been operating at the grass-roots level as well as attempting to infiltrate senior levels of government,” he said, pointing to the 2015 arrest of Dino Bouterse, the son of Suriname’s president, for inviting Hezbollah agents to establish a base in his home country in exchange for $2 million that was ultimately not paid.

Under the current conservative government of Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil has made a U-turn with regard to its Iran policy. As an inevitable corollary, the country now has little tolerance for Hezbollah’s activities in the region. Argentinian foreign policy too has swung in the same direction as Brazil.

An upshot of the rightward shift in the region’s political mood was the arrest in September 2018 by Brazilian authorities of Assad Ahmad Barakat, a man the Americans have long considered a key financier for Hezbollah.

In contrast with the hardening stances of Brazil and Argentina, the government of Venezuelan socialist President Nicolas Maduro views Hezbollah as a natural ally as part of a policy first adopted by his predecessor, Hugo Chavez, who deepened ties with Iran when he came to power in 1999.

Against this mixed background, security analysts say subterfuge and criminality remain the key elements of Hezbollah’s South America strategy. They say it will not be easy to cut Hezbollah down to size and deny it the ability to influence governments — or to carry out terror attacks if it wants to avenge the killing of Soleimani.

There are possibly drug traffickers active in South America who are sympathetic to Hezbollah’s cause, the analysts say, adding that the fact that a group in control of 12 seats in the Lebanese parliament is involved in drug trafficking and fundraising halfway across the world is deeply worrisome, even without their terrorist connotations.

Nuseibeh asserts that, going forward, “it is likely Latin America will be an even more important frontier for Hezbollah as it is a region in which the group has invested so many resources.”

Clearly, in the absence of a firm and coherent response to Hezbollah’s activities in South America, the organization, fired with a zeal to avenge the death of Soleimani, could pose a serious security threat to the Western Hemisphere and beyond in the days to come.