PARIS: South Africa’s first all-race vote 25 years ago turned the page on an oppressive system of racial segregation called apartheid that for roughly 50 years privileged whites over blacks.

Here is a reminder.

Apartheid — an Afrikaans-language word meaning the state of “apartness” — became official government policy in 1948 when the conservative National Party took power.

It formalized a system of white-minority domination in place soon after European settlers started arriving on the southern tip of Africa more than 300 years before, most coming from The Netherlands and Britain.

Apartheid was built on laws that classified people as black, colored (mixed race), Indian or white.

The races were separated in every aspect including at school, work and hospitals, and where they could live and shop.

Jobs were reserved for certain races; marriage and sex across the color bar was forbidden; even beaches, buses and park benches were allotted according to skin color.

Whites — who made up less than 20 percent of the population — had ownership of more than 80 percent of the land. They controlled the economy, including the lucrative mining sector, and all political levers.

Blacks had no right to vote and were relegated to inferior jobs, education and services.

They were made to live in neglected townships on the outskirts of urban areas or in various disadvantaged ethnic-based homelands called “Bantustans.”

Until 1986 black South Africans were obliged to carry a passport-like document called a pass book which restricted their movements.

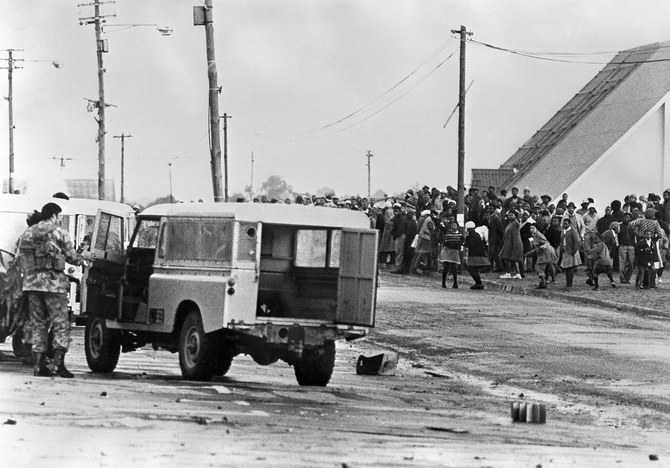

To maintain the system, the apartheid government imposed severe censorship and relied heavily on its security forces, with compulsory conscription for white males between 1967 and 1993.

The African National Congress (ANC) led the resistance to apartheid, first adopting non-violent tactics such as strikes, boycotts and civil disobedience campaigns.

Among the first major protests was a boycott of government buses in the Alexandra township in 1957.

In 1960 a march in Sharpeville against the hated pass books became a massacre when police opened fire on the crowd, killing 69 blacks.

In 1960 the government banned the ANC and other black opposition, and imposed a state of emergency. Underground and in exile, the ANC turned to armed struggle.

In 1964 one of its leaders, Nelson Mandela, was sentenced with others to life in prison for sabotage. He was behind bars for 27 years, becoming the world’s best-known political prisoner of the time and an icon of the anti-apartheid struggle.

The Sharpeville massacre brought world attention to the regime’s brutal repression, leading to the start of its international isolation.

South Africa was excluded from the Olympic Games, expelled from the United Nations, put under arms and trade embargoes.

Internationally renowned personalities became activists against apartheid, with a major rock concert at London’s Wembley Stadium in 1988 honoring Mandela.

It came as a shock when in 1990 President F.W. de Klerk, in power for just five months, announced the legalization of the black opposition.

Within days Mandela walked free after 27 years in jail; within a year and a half, apartheid was over, its discriminatory laws undone.

Its dismantling was celebrated with the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Mandela and de Klerk.

The transition to democracy was not without hurdles with white extremists violently resistant and rivalry between ANC militants and the Zulu party Inkhata breaking into deadly violence.

The first all-race elections were held in 1994 and black South Africans queued for hours to cast a vote for the first time in their lives.

The ANC won by a landslide and Mandela became the country’s first black president. Apartheid was over.

Apartheid, the race-based system ended 25 years ago

Apartheid, the race-based system ended 25 years ago

- Apartheid — an Afrikaans-language word meaning the state of apartness — became official government policy in 1948

- It formalized a system of white-minority domination in place soon after European settlers started arriving on the southern tip of Africa more than 300 years before

More than 200 killed in coltan mine collapse in east Congo, official says

- “Some people were rescued just in time and have serious injuries,” Muyisa

- An adviser to the governor said the number of confirmed dead was at least 227

KINSHASA: More than 200 people were killed this week in a collapse at the Rubaya coltan mine in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, Lubumba Kambere Muyisa, spokesperson for the rebel-appointed governor of the province where the mine is located, told Reuters on Friday.

Rubaya produces around 15 percent of the world’s coltan, which is processed into tantalum, a heat-resistant metal that is in high demand by makers of mobile phones, computers, aerospace components and gas turbines.

The site, where locals dig manually for a few dollars per day, has been under the control of the AFC/M23 rebel group since 2024.

The collapse occurred on Wednesday and the precise toll was still unclear as of Friday evening.

“More than 200 people were victims of this landslide, including miners, children and market women. Some people were rescued just in time and have serious injuries,” Muyisa said, adding that about 20 injured people were being treated in health facilities.

“We are in the rainy season. The ground is fragile. It was the ground that gave way while the victims were in the hole.”

An adviser to the governor said the number of confirmed dead was at least 227. He spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to brief the media.

The United Nations says AFC/M23 has plundered Rubaya’s riches to help fund its insurgency, backed by the government of neighboring Rwanda, an allegation Kigali denies.

The heavily-armed rebels, whose stated aim is to overthrow the government in Kinshasa and ensure the safety of the Congolese Tutsi minority, captured even more mineral-rich territory in eastern Congo during a lightning advance last year.