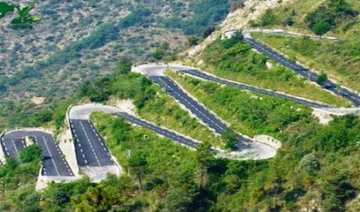

SHIMSHAL HUNZA, Pakistan: The jeep bumps along a sloppy mud road carved between Pakistan’s northern mountains, its tires running with breathtaking precision along the very edge, where nothing but air lies between them and the snake-like river winding hundreds of feet below.

More than 3,000 meters (around 10,000 feet) above sea level the vehicle has no room for error, its other side just inches from scraping along the rock face, its passengers worriedly monitoring how anxious the driver appears.

For his part, Shahid Karim spends as much of his time watching the mountains themselves as he does gauging how close he is bringing his jeep to the edge.

“At every second death is written on this road... This whole area is notorious for landslides,” he says, adding that falling rocks have struck his vehicle many times.

The precarious roads of Pakistan’s mountainous north are lifelines for its scattered and remote population. The thoroughfare Karim is traveling is the only one connecting the 2,400 residents of the village of Shimshal to the outside world.

Drivers like Karim, a native of the region who has been navigating this particular stretch of road since 2004, are the only ones who use them, making a career out of ferrying villagers, tourists, and the handful of Westerners who make the knuckle-whitening journey each year.

They are the ones with the experience to know that landslides are as great a threat as the road’s narrowness and lack of safety barriers.

During spring and autumn, when there is no snow or rain, an ibex walking delicately along the heights can trigger a rockfall, while a strong breeze on a summer’s day can set pebbles sliding away.

The lightest rainfall can shift rocks, while in the frozen winters even sunlight can be dangerous, melting the snow that surrounds boulders and prevents them from raining down on the road.

Sometimes rocks falling from above are less of a danger than those tumbling away beneath the car tires, loosened by the weight of the vehicle and sent crashing down into the abyss.

The more desperate passengers are for the journey to end, the slower the driver is forced to crawl along the roads.

“We have passengers with us whose lives depend on us,” Karim says. “So it is really important to drive slowly.”

This road was inaugurated in 2003 after 18 years of labor by locals in which three villagers lost their lives.

Before then, the people of Shimshal had to walk for days, crossing icy rivers and climbing deadly ridges in freezing temperatures to reach the nearest large village of Passu.

Previous rulers of Hunza, the former principality that encompasses Shimshal and now forms part of Pakistan’s northern Gilgit-Baltistan region, would banish criminals to Shimshal as punishment.

The suffering lay in the journey, which was so tough that few survived it, most slipping to their death from precarious ridges with others succumbing to cold and pneumonia.

The road, despite causing so much fear in the hearts of tourists, is therefore seen as a blessing by residents of Shimshal, bringing education and basic amenities to their remote mountain homes.

That includes electricity: for years residents have generated power with small solar panels, though this year a hydropower plant built with materials brought in along the road is set to be completed.

Every morning the sound of a blaring car horn tears into the dawn serenity of Shimshal.

Its residents are not bothered by the rude awakening. So few people dare drive the road that — barring emergencies — those who wish to travel outside crowd into just one vehicle that leaves daily. Its driver is simply making sure no one misses the journey.

A mere six vehicles from Shimshal and four from Passu regularly make the commute. The villagers muster at a single point with their luggage as the driver continues cruising through the village honking, sometimes for up to half an hour.

Doulat Amin, the first teacher to work in Shimshal valley, is among the people waiting one rainy dawn to get into central Hunza.

“I came here in 1966 as a teacher and there were so many difficulties back then,” the 75-year-old said.

“There was no education, because there was no road.”

Traveling its rocky way is risky — but, Amin says, God is with the passengers.

“We plead with him every time we travel on the road.”

Daring death on the remote roads of Pakistan’s north

Daring death on the remote roads of Pakistan’s north

Pakistan, Saudi Arabia resolve to strengthen economic cooperation during Davos summit

- Pakistan finmin Muhammad Aurangzeb meets Saudi Arabia's Investment Minister Khalid bin Abdulaziz Al-Falih

- Al-Falih appreciated Pakistan's potential, particularly its natural resources, strategic location, says Pakistan Finance Division

KARACHI: Pakistan's Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb and Saudi Investment Minister Khalid bin Abdulaziz Al-Falih met in Davos this week, resolving to strengthen ongoing bilateral cooperation by working closely together and maintaining high-level contact, Pakistan's Finance Division said.

Islamabad and Riyadh have moved closer to broaden their cooperation in recent months, signing a landmark defense pact in September 2025 and agreeing to launch an economic cooperation framework a month later to strengthen bilateral trade and investment relations.

Aurangzeb met Al-Falih during the sidelines of the 56th annual World Economic Forum (WEF) summit in Davos on Thursday, Pakistan's Finance Division said in a statement. The two sides reviewed ongoing cooperation and reviewed progress on existing and planned projects across various sectors, the statement added.

"Both sides reiterated their strong resolve to expand bilateral collaboration by working closely together, strengthening institutional linkages and maintaining regular high-level contacts," Pakistan's Finance Division said on Thursday.

"They agreed that sustained engagement and mutual understanding would help translate shared objectives into concrete and mutually beneficial initiatives."

The Finance Division said Al-Falih appreciated Pakistan's importance and potential, particularly its natural resources, strategic location and emerging opportunities for investment.

"The meeting concluded in a positive and forward-looking spirit, with both ministers expressing confidence that closer partnership and continued dialogue would further strengthen economic and investment ties between Pakistan and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia," the statement said.

The two countries enjoy cordial relations dating back decades and firmly grounded in shared values, culture, faith and economic ties. The Kingdom is home to over two million Pakistani expats, making it the largest source of foreign remittances for cash-strapped Pakistan.

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia signed 34 business agreements worth $2.8 billion across multiple sectors in 2024, further strengthening their economic cooperation.

Riyadh has also bailed Pakistan frequently out of economic crises over the years, providing it crucial loans and oil on deferred payment basis.