ABU DHABI: Arab artists from countries across the Middle East and North Africa, including Palestine, Syria, Egypt and Morocco, shared visions of their homelands and experiences this week at the Beirut Art Fair.

The Samer Kozah Art Gallery in Damascus, the only Syrian gallery at this year’s event, displayed works by 12 Syrian painters and sculptors.

“Most of them are now based in Vienna, Paris, Denmark, Dubai, Beirut, and a few in Syria,” said Samer Kozah, the gallery’s founder and manager for the past 24 years. “It’s safer and easier for them to work from outside. I don’t know when they will come back but I hope they do — you can feel the country in their artwork.”

The annual fair, which runs from Sept. 20 to 23, offers a platform for Arab artists to present their work to the outside world, something that is much needed by those from areas embroiled in conflict and turmoil.

“Nobody comes to Damascus to see art anymore,” Kozah said. “They can see it online, send emails or view on Instagram but they used to come a lot more. The main market for Syrian art in the past was Lebanese and Gulf collectors.”

Mohamed Ablaon . (Image supplied)

Most galleries in Syria struggled during the civil war and were forced to close between 2013 and 2017, though there are signs of a slow recovery.

“It really affected the art industry here but most of them are now open, although it’s a bit quiet,” he said. “Everything can be shipped from here, but the Beirut Art Fair can always help.”

Palestinian artists face similar challenges, as many of them are unable to travel to showcase their work.

“The majority are based in Ramallah, others in Jerusalem, the Occupied Territories, Gaza and in the diaspora,” said Ziad Anani, director of the Zawyeh Gallery in Ramallah. “Their work is mainly political — even if it’s a landscape or a Palestinian family, many show the wall, the prisons, the construction and how we are losing the land.

“Palestinian artists are describing their emotions through their work and the surroundings they live in, from the checkpoints and occupation to the distances traveled.”

Many, however, are unable to travel to the fair to see their work on display due to passport issues.

“Some hold Palestinian papers and it’s even harder to get out of Palestine, so it’s not comfortable for them,” said Anani. “It’s not fair that all the other artists from around the world can see their work but Palestinian artists cannot. It seems like they are in prison; they cannot travel and cannot see the world, when they should be hearing other people’s opinions about their work, hear curators and see other artwork, so it’s a struggle.”

He said the only way people can learn about and understand this struggle the artists face is by seeing their work.

“It is through the art that we exhibit and the messages they send from that art,” he added. “We work with about 25 artists that work with paint, oil or acrylic, video, photography and cultural installations, and the event will be an opportunity to reach out to those who are interested in Palestinian art.”

He described Beirut as the cultural hub of the Middle East.

Hicham Benohoud. (Image supplied)

“It’s always focused on art and culture, and they also have a good number of Palestinians who live in Lebanon,” he said. “We know Palestinian art collectors living there and new initiatives, such as Dar El-Nimer (in Beirut, an interactive space dedicated to the culture of Palestine and the wider Arab world), are interested in collecting Palestinian art so, for us, Beirut is a good spot where we can reach out to those people and try to promote the work.”

Lama Koubrously, head of collections at Dar El-Nimer, said the art scene in Lebanon has been growing thanks to new art spaces, especially in Beirut.

“As an art foundation dedicated to showcasing cultural and artistic productions from the Arab world and the region, we believe it is a necessity to have a platform to raise awareness of art practices, including film screenings, debates, exhibitions, workshops and auctions,” she said. “Moreover, Dar El-Nimer is a place that invites both professionals and amateurs to exchange dialogue with regard to the current art scene shaping the region. Over the years the Beirut Art Fair has been bringing an influx of people from the art world, which is putting Lebanon on the art map.”

Karim Francis, owner of the Karim Francis Art Gallery in Egypt, agrees.

“If you look at the Middle East, what is left are the Emirates, Egypt and Lebanon,” he said. “Lebanon is a small country but it’s quite active and there is a lot of interest in art. Each country usually looks to his own artists, but Lebanon looks to its own and also around – in the end it’s all linked in one area.”

Francis, who is participating at the fair for the first time, is part of the Egyptian pavilion, where he will showcase pieces inspired by Coptic, Islamic, folkloric and Egyptian art.

“It gives a small panorama into what’s going on in Egypt,” he said. “The art scene across the region is growing and becoming more active.”

Gallery Misr, also from Egypt, works with seven artists and presented their work at the fair.

Hosni Radwan"Out of Place". (Image supplied)

“Beirut has more of a personality than other places where you find art fairs,” said gallery founder Mohamed Talaat, who worked for 12 years at the Egyptian Ministry of Culture. “Dubai is more global but Beirut has something different about it. It has great culture and a good connection with Paris.”

The fair this year featured more than 50 art galleries from 20 countries, exhibiting more than 1,600 works by 250 artists. It includes 18 first-time exhibitors, alongside 33 returning galleries, with two sections dedicated to galleries that focus on modern and contemporary art from the region.

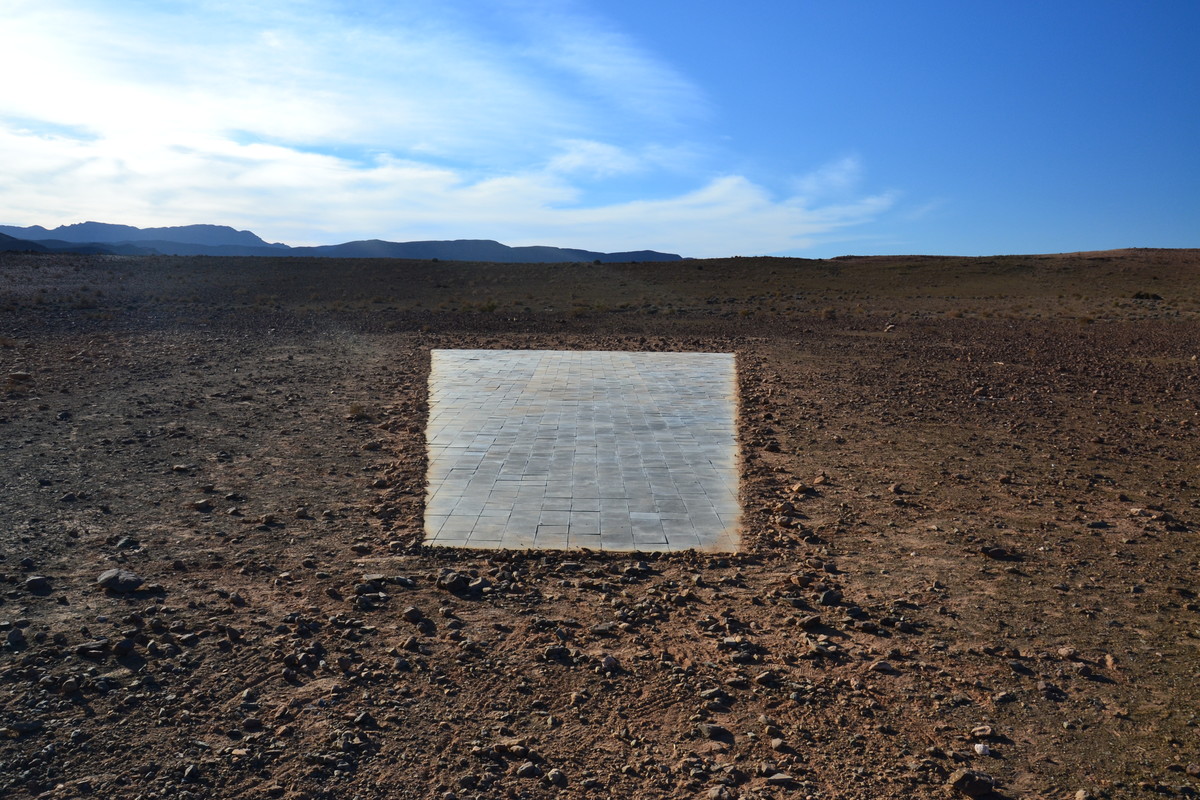

“To me, the fair is an interesting place to exhibit, as a local and international artistic platform with many collectors, galleries and foundations, not only from Lebanon but also Europe, Africa and Asia,” said Jacques-Antoine Gannat, international development director at the Loft Art Gallery in Morocco, which exhibited Moroccan photographer Hicham Benohoud’s new series, “Landscaping.”

“For us, it’s also the link between the Maghreb and the Middle East, with its similarities and differences.

The fair is ‘human-size,’ which allows collectors and galleries to meet more easily than at some bigger fairs.”