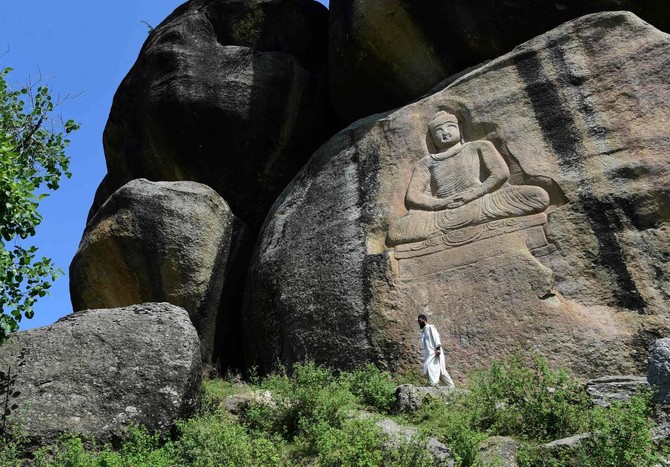

MINGORA: The Buddha of Swat, carved on a cliff in the seventh century, was dynamited by the Pakistani Taliban in 2007. Now it has been restored, a powerful symbol of tolerance in the traumatized Pakistani valley.

The holy figure, depicted in a lotus position at the base of a granite cliff in northern Pakistan, was severely damaged by Islamist insurgents in an echo of the Afghan Taliban’s complete destruction of its more imposing counterparts at Bamiyan in 2001.

For some, it was a wanton act of vandalism that struck at the heart of the area’s unique history and identity.

It felt “like they killed my father,” says Parvesh Shaheen, a 79-year-old expert on Buddhism in Swat. “They attack... my culture, my history.”

The Buddha sits in Jahanabad, the epicenter of Swat’s Buddhist heritage, a beautiful valley in the foothills of the Himalayas.

There the Italian government has been helping to preserve hundreds of archaeological sites, working with local authorities who hope to turn it into a place of pilgrimage once more and pull in sorely needed tourist dollars.

A decade ago, the militants climbed the six-meter (20-foot) effigy to lay the explosives, but only part of them were triggered, demolishing the top of the Buddha’s face. Another, smaller fresco nearby was torn to pieces.

For Shaheen, the statue is “a symbol of peace, symbol of love, symbol of brotherhood.”

“We don’t hate anybody, any religion — what is this nonsense to hate somebody?” he says.

But other Swatis, less familiar with history and in 2007 not yet traumatized by the full brutality of the Taliban, applauded the attack and took up the argument that sculpture was “anti-Islamic.”

Like their counterparts in neighboring Afghanistan, the Pakistani Taliban are extremist insurgents who terrorized the population in the name of a fundamentalist version of Islam, banning all representation in art and for whom the idea of a non-Islamic past is taboo.

The episode became a marker for the beginning of the Taliban’s violent occupation of Swat, which would only end in 2009 with heavy intervention by the Pakistan army. By then, several thousand people had been killed and more than 1.5 million displaced.

Holy land

The population of Swat has not always been as it is today, mostly conservative Muslim, where cultural norms dictate that women wear burqas.

Instead, it was for centuries a pilgrimage site for the Buddhist faithful, especially from the Himalayas. The Vajrayana school even consider it a “holy land,” from where their faith originated.

They continued to visit right up until the 20th century, when borders hardened with the independence of British India and creation of Pakistan in 1947.

Now the vast majority of Pakistan’s population are Muslim, and its religious minorities — mainly Christians and Hindus — are often subject to discrimination or violence.

Buddhism for its part disappeared from the region around the 10th century AD, driven out by Islam and Hinduism.

Its golden age in Swat lasted from the second to the fourth centuries, when more than 1,000 monasteries, sanctuaries and stupas spread out in constellations across the valley.

“The landscape was worshipped in itself,” says Luca Maria Olivieri, an Italian archaeologist who oversaw the restoration of the Buddha.

“The pilgrims were welcomed by these protective images, sculptures and inscriptions, arranged along the last kilometers (miles) before arriving,” Olivieri explains.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation of the site has not been easy, he says. Carried out in phases, it began in 2012 with the application of a coating to protect the damaged part of the sculpture.

The reconstruction of the face itself was first prepared virtually in the laboratory, in 3D, using laser surveys and old photos.

The last phase, the actual restoration, ended in 2016. Olivieri says the reconstruction is not identical, but that is deliberate, as “the idea of damage should remain visible.”

The Italian archaeological mission in Swat, which he directs, has been there since 1955 — though it was briefly forced from the valley during Taliban rule.

It manages other excavation sites and supervised the restoration of the archaeological museum in Mingora, the main city of Swat, damaged in an attack in 2008.

The Italian government has invested 2.5 million euros ($2.9 million) in five years for the preservation of Swat’s cultural heritage, striving to involve the local population as much as possible.

Now authorities are counting on the Buddha’s recovered smile and iconic status to boost religious tourism from places such as China and Thailand.

Years after the Taliban were ousted, the valley is largely rejuvenated, though at times security is still tense, with an attack killing 11 soldiers in February this year.

Some people in Swat also see the Buddha as a tool for promoting religious tolerance.

Fazal Khaliq, a journalist and author living in Mingora, thinks the threat to cultural heritage has been “minimized” through education and the use of social networks to spread a “soft, good” image.

However, “the majority of people who are not young, educated — they still do not understand” its importance, he admits.

Meanwhile the museum in Mingora now welcomes mullahs “who like Buddhism,” says its curator, Faiz-ur-Rehman.

“Before Islam, this was our religion,” he says.