DUBAI: With daring filmmakers, untold stories and entertainment-starved young people, Saudi Arabia has all the makings of a local movie industry — except for theaters.

As the traditionally austere Kingdom cautiously embraces more forms of entertainment, local filmmakers are exploring a new frontier in Saudi art, using the Internet to screen films and pushing boundaries of expression — often with surprise backing from top royals.

“Saudi Arabia is the future of filmmaking in the Gulf,” said Butheina Kazim, co-founder of Dubai’s independent cinema platform “Cinema Akil,” pointing to a crop of Saudi films that have emerged in recent years.

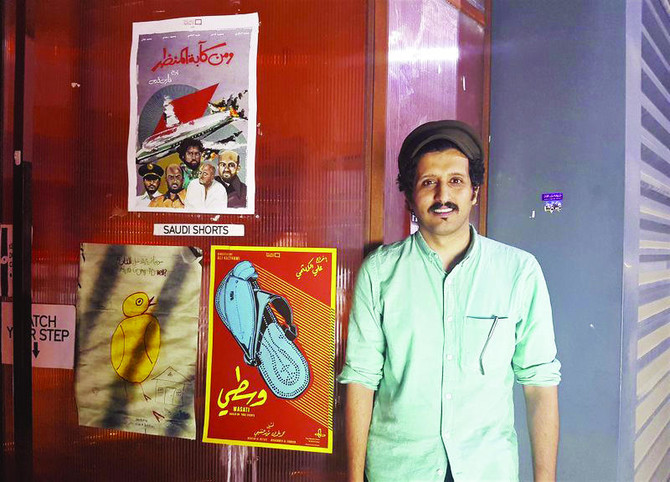

Kazim screened three Saudi short films to audiences in Dubai last month, including one called “Wasati”, or moderate in Arabic. The movie is based on a real-life event that took place in the mid-1990s when a group of ultraconservatives rushed the stage during a play in Saudi Arabia and shut it down. The incident dampened theater in Saudi Arabia for years.

The film by Ali Kalthami was screened in Los Angeles last year, and was shown for one night in June at Riyadh’s Al Yamamah University — in the same theater where the play was shut down two decades ago.

One of Saudi Arabia’s most prominent film pioneers, Kalthami is co-founder of C3 Films and Telfaz11, a popular YouTube channel that has amassed more than 1 billion views since it was launched in 2011.

His movie “Wasati” was one of several Saudi shorts produced last year with funding from the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, an initiative named after the founder of the kingdom by Saudi Arabia’s state-oil company Aramco. Kalthami said it was the first time he would ever received funding for a film from a state-linked entity.

“I think because of the history we made online... they trusted we could tell wonderful stories, human stories in Saudi,” he said.

By using the Internet to show films, Telfaz11 and other Saudi production houses have managed to circumvent traditional distribution channels and make do without cinemas. Even so, Saudi filmmakers have to contend with how to tell their stories within the bounds of the kingdom’s ultraconservative mores and its limits on free speech.

It was not always like this. There used to be movie theaters across Saudi Arabia from the 1960s through the 1980s, until religious hard-liners were given greater sway over public life. In the years that followed, Saudis could rent movies from video stores, though scenes of lovemaking and cursing were edited out. Saudis also had access to movies on satellite channels.

Nowadays, Saudis can stream movies online — where Telfaz11 has partnered with YouTube.

Some of the local films being produced are purely for entertainment, while others wade into the myriad everyday challenges people in Saudi Arabia face.

The film “Wadjda” made history in 2013 by becoming the first Academy Award entry for Saudi Arabia, though it was not nominated for the Oscars. The movie follows the story of a 10-year-old girl who dreams of having a bicycle just like the boys in her ultraconservative neighborhood, where men and women are strictly segregated and where boys and girls attend separate schools. The film was written and directed by Saudi female director Haifaa Al-Mansour, who shot the film entirely in the kingdom.

Saudi Arabia is vying again this year for an Oscar in the foreign-language film category. The film “Barakah Meets Barakah”, by director Mahmoud Sabbagh, made its premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival in February. The movie, which has been called the kingdom’s first romantic comedy, tells the story of a civil servant who falls for a Saudi girl whose Instagram posts have made her a local celebrity.

Though four years apart, the two films tackle the issue of gender segregation in Saudi Arabia, which remains strictly enforced.

The emergence of a Saudi film scene is happening as the kingdom begins to loosen the reins on fun and entertainment after nearly two decades without cinemas or concerts.

Saudi Arabia’s 31-year-old heir to throne, Mohammed bin Salman, is set to inherit a nation where more than half of the population is under 25, and most are active on social media, where they can access the world beyond the reach of state censors.

The crown prince is behind an ambitious blueprint to transform Saudi Arabia’s economy and society. He wants to encourage Saudis to spend more of their money locally, including doubling what Saudi families spend on entertainment in the kingdom.

While Saudi Arabia’s influential clerics and many citizens consider Western-style entertainment sinful, the prince’s backing means there could soon be cinemas in the kingdom. Prince Mohammed’s nonprofit, MiSK, sponsored a screening in August of an Arabic 3D action film in the capital, Riyadh. There have been other similar screenings in the coastal city of Jiddah.

The government has also backed a Saudi film festival that is taken place for the past few years in the eastern city of Dhahran. This year, some 60 Saudi films were screened.

After watching the Saudi shorts in Dubai’s Cinema Akil and meeting the filmmakers, aspiring filmmaker Lamia Al-Shwwier, who is just graduated with a master’s degree from the Los Angeles campus of the New York Film Academy, said she felt confident about the prospects of a Saudi film industry.

“We have so many incredible stories to tell, whether they are stories of success or challenge. Our society is rich in stories and ideas,” she said.

Saudi filmmakers build audiences without cinemas

Saudi filmmakers build audiences without cinemas

As an uncertain 2026 begins, virtual journeys back to 2016 become a trend

- Over the past few weeks, millions have been sharing throwback photos to that time on social media, kicking off one of the first viral trends of the year

LONDON: The year is 2016. Somehow it feels carefree, driven by Internet culture. Everyone is wearing over-the-top makeup.

At least, that’s how Maren Nævdal, 27, remembers it — and has seen it on her social feeds in recent days.

For Njeri Allen, also 27, the year was defined by the artists topping the charts that year, from Beyonce to Drake to Rihanna’s last music releases. She also remembers the Snapchat stories and an unforgettable summer with her loved ones. “Everything felt new, different, interesting and fun,” Allen says.

Many people, particularly those in their 20s and 30s, are thinking about 2016 these days. Over the past few weeks, millions have been sharing throwback photos to that time on social media, kicking off one of the first viral trends of the year — the year 2026, that is.

With it have come the memes about how various factors — the sepia hues over Instagram photos, the dog filters on Snapchat and the music — made even 2016’s worst day feel like the best of times.

Part of the look-back trend’s popularity has come from the realization that 2016 was already a decade ago – a time when Nævdal says she felt like people were doing “fun, unserious things” before having to grow up.

But experts point to 2016 as a year when the world was on the edge of the social, political and technological developments that make up our lives today. Those same advances — such as developments under US President Donald Trump and the rise of AI — have increased a yearning for even the recent past, and made it easier to get there.

2016 marked a year of transition

Nostalgia is often driven by a generation coming of age — and its members realizing they miss what childhood and adolescence felt like. That’s certainly true here. But some of those indulging in the online journeys through time say something more is at play as well.

It has to do with the state of the world — then and now.

By the end of 2016, people would be looking ahead to moments like Trump’s first presidential term and repercussions of the United Kingdom leaving the EU after the Brexit referendum. A few years after that, the COVID-19 pandemic would send most of the world into lockdown and upend life for nearly two years.

Janelle Wilson, a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota-Duluth, says the world was “on the cusp of things, but not fully thrown into the dark days that were to come.”

“The nostalgia being expressed now, for 2016, is due in large part to what has transpired since then,” she says, also referencing the rise of populism and increased polarization. “For there to be nostalgia for 2016 in the present,” she added, “I still think those kinds of transitions are significant.”

For Nævdal, 2016 “was before a lot of the things we’re dealing with now.” She loved seeing “how embarrassing everyone was, not just me,” in the photos people have shared.

“It felt more authentic in some ways,” she says. Today, Nævdal says, “the world is going downhill.”

Nina van Volkinburg, a professor of strategic fashion marketing at University of the Arts, London, says 2016 marked the beginning of “a new world order” and of “fractured trust in institutions and the establishment.” She says it also represented a time of possibility — and, on social media, “the maximalism of it all.”

This was represented in the bohemian fashion popularized in Coachella that year, the “cut crease” makeup Nævdal loved and the dance music Allen remembers.

“People were new to platforms and online trends, so were having fun with their identity,” van Volkinburg says. “There was authenticity around that.”

And 2016 was also the year of the “boss babe” and the popularity of millennial pink, van Volkinburg says, indications of young people coming into adulthood in a year that felt hopeful.

Allen remembers that as the summer she and her friends came of age as high school graduates. She says they all knew then that they would remember 2016 forever.

Ten years on, having moved again to Taiwan, she said “unprecedented things are happening” in the world. “Both of my homes are not safe,” she said of the US and Taiwan, “it’s easier to go back to a time that’s more comfortable and that you felt safe in.”

Feelings of nostalgia are speeding up

In the last few days, Nævdal decided to hide the social media apps on her phone. AI was a big part of that decision. “It freaks me out that you can’t tell what’s real anymore,” she said.

“When I’ve come off of social media, I feel that at least now I know the things I’m seeing are real,” she added, “which is quite terrifying.”

The revival of vinyl record collections, letter writing and a fresh focus on the aesthetics of yesterday point to nostalgia continuing to dominate trends and culture. Wilson says the feeling has increased as technology makes nostalgia more accessible.

“We can so readily access the past or, at least, versions of it,” she said. “We’re to the point where we can say, ‘Remember last week when we were doing XYZ? That was such a good time!’”

Both Nævdal and Allen described themselves as nostalgic people. Nævdal said she enjoys looking back to old photos – especially when they show up as “On This Day” updates on her phone, She sends them to friends and family when their photos come up.

Allen wished that she documented more of her 2016 and younger years overall, to reflect on how much she has evolved and experienced since.

“I didn’t know what life could be,” she said of that time. “I would love to be able to capture my thought process and my feelings, just to know how much I have grown.”