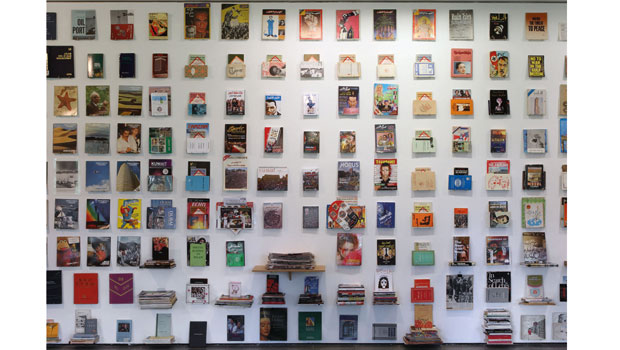

Having begun in 2009, it holds thousands of comics, pamphlets, magazines, industry and ministry publications, government and pop-culture propaganda, pulp books, joke books and other printed material. With each stop, the collection grows, getting denser in its concept: an exploration of the idea of what the Middle East is through the framework of books.

The London display has a few special additions. They include a collection of books found at the former German Democratic Republic’s abandoned Iraqi embassy in East Berlin. It also includes a collection of various types of printed matter and ephemera brought over from Cairo in parallel with the latest issue of Bidoun, devoted to last spring’s Egyptian revolution.

The Bidoun Library group, the collective managing the project, hunt bookstores over the Internet and all around these different cities, finding books under five US dollars (another loose stipulation as to what is included in the collection) that fit the conceptual criteria. The collection’s main premise is to look into the idea of the Middle East as a colonial impression.

In explaining what they are presenting, Babak Radboy, member of the Library group and creative director of Bidoun, said: “The Middle East is a place in relation to other places, rather than within itself. The library is about the Middle East as an object in text not as a real site, but as a place that’s been articulated in novels, cook books, joke books, guide books, oil directories and technical manuals.”

Senior Editor of Bidoun, also a member of the group, Michael C. Vazquez added that their attempt is to create “a composite picture” of the Middle East. “We are less interested in the subject than the context,” he explained.

Referring to a particular geographic area, the term “Middle East” was coined based on its relation to Europe. Therefore, in finding the books that place it as such, the question is how concrete is this idea of a united region?

“The reality is that you cannot separate culture from any political autonomy,” Radboy responded. “There are often moments where someone in Morocco couldn’t care less about what is happening in Kuwait, or someone in Saudi Arabia cannot relate to anything happening to someone in Jordan. These are all very different places. There’s a language that goes across but even that is very different throughout. It gets more complicated when you are in the Middle East. To the West, it is all referred to as ‘those people over there.’”

This is communicated rather clearly through the books’ overall impression of the “Arab” or “Middle Easterner,” caricaturized in their relation to oil, war, espionage and exoticism (usually in the form of belly dancing). These characteristics, repeated in different forms in different publications make up the one-dimensional impression of the general Middle East: wealthy, exotic, dangerous and unknown. Reflecting this most blatantly is an entire wave of pulp novels from the early 70s commissioned by publishers with very particular ideas of how they wanted stories to arc and what the characters should represent.

“It was like a weird fictional response to the oil crisis. But it’s hard to say whether it was an objective or market. It’s a little bit of both,” added Radboy. Among the books that stand out is “Turn the Other Sheik,” a pulp adult spy novel about an undercover operation in the fictional country of Kuaydan, “the West’s major source of petroleum,” the blurb explains.

An entire section of one wall is devoted to different books with the title “The Arabs.” These books, ranging in their angle from looking at political contexts in relation to Israel to actually focusing on the Arab people, have a commonality which is that they all ambitiously generalize. They attempt to look at Arab regional history, society, culture, religion, politics and geography, dating back from the days of the Prophet to the future imagined by their respective authors in 300 to 500 pages.

Looking at history, however, it is easy to lose sight of how far back one can actually recount. Questioning how borders were drawn and governments took power, much of the current political build of the Middle East is indeed colonial. Yet, Radboy’s response was more open regarding this note. “The library,” he explains, “is interested in the misunderstanding just as much as the correct understanding.”

Looking at the books as pieces of media that propagate a certain idea, they now hold a value that is beyond their purpose. The books in the collection are not necessarily treated as sources of knowledge but as objects that communicated something that society now exists beyond. Focusing on the cheap books, allows this “object” aspect to stand out even more. These include romance novels, outdated Western academic studies on Arabs (including a study of Arab shoplifters in London) and a collection of ARAMCO World magazines. These publications, each written with a particular audience in mind, have already stood their time and are now outdated in their medium as well as the reality they attempt to convey. It is into this focus that the collection of found books from the abandoned Iraqi embassy in East Berlin fit in.

Sophie-Therese Trenka-Dalton and Hannes Schmidt are two artists from Berlin currently working on a publication about the books they found at the embassy site. Books highlighting the progress made by the Ministries of Development and Agriculture as well as the repetitive image of Saddam Hussein stand as outdated matter in reference to a no-longer existing regime.

With foresight of seeing them in the same vein in the future are the books displayed coming from Cairo.

As Vazquez explains, the Library Group aimed to buy every book that had been published in Cairo since January. What resulted is a collection whereby magazines, ephemera and other matter are unusually politicized. From teen to women’s magazines, calendars and other material, revolution is everywhere.

“Even the sports books and fitness magazines are all about the revolution. You see all the different people who are affected by it — even the advertisers, but this doesn’t last. Same in Iran; they were fearless for about six months, even gossip magazines, but gradually, that starts to disappear,” said Radboy.

The Bidoun Library, in its aim to highlight the abstractness of the notion of the Middle East has offered a display that straddles between being laughable, enlightening, offensive and even, in some areas, ironically nostalgic. The fragmented collage that these books present is very clear in the nouveau riche, exoticness that other forms of media such as cartoons and films from the West have portrayed as Arab people. The collection, having by now grown with finds from the Eastern and Western cities that the Library has been installed in, is an impressive show of realities, propagandas and fictions regarding the so-called Middle East and its people.