LONDON: When Abu Dhabi’s Zayed National Museum opens its doors to the public on Dec. 3, the first thing visitors will see as they enter is a remarkable sailing boat — a hypothetical recreation of a merchant ship of the type that would have sailed the Arabian Gulf in the Bronze Age.

Ancient records written in cuneiform, an early form of writing etched into clay tablets, tell us that 4,000 years ago such vessels linked far-flung communities and cultures, from ancient Mesopotamia to the Indus Valley in modern-day India and Pakistan.

They carried large cargoes, including copper and pottery, and called at ports and trading posts along the coasts of modern-day Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar and the UAE.

A view of the Zayed National Museum. (Supplied)

The boat represents only part of the story of the UAE, which unfolds over six galleries in the museum, including an outdoor “living gallery” garden, devoted to its history, landscapes and culture, while honoring its late founder, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al-Nahyan.

The museum, designed by the acclaimed British architect Norman Foster, and set to open during the same week as UAE National Day, is a striking addition to the cultural district on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island.

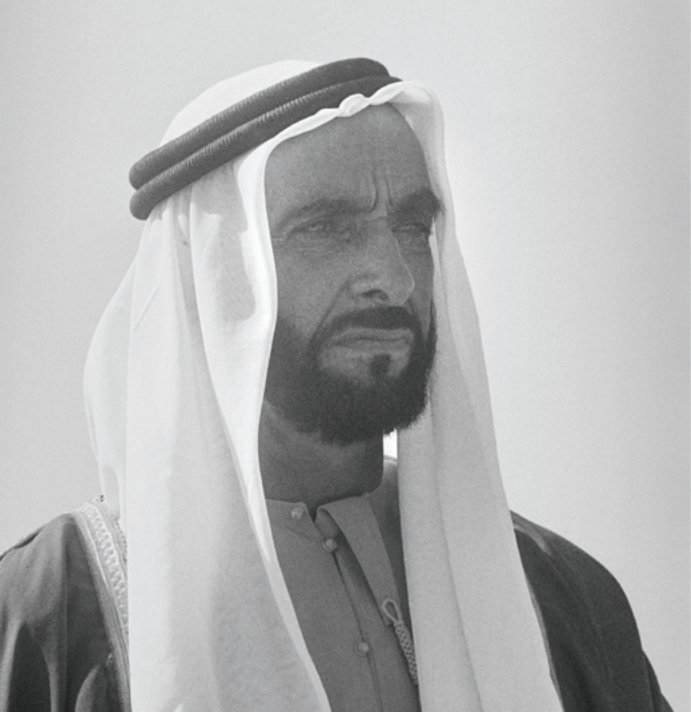

Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al-Nahyan. (Supplied)

Linked by bridge to the capital city, the district is already home to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the multifaith Abrahamic Family House, the recently opened Natural History Museum, and the forthcoming Guggenheim Museum.

The five monumental towers that rise above Zayed National Museum represent the wingtip feathers of the falcon — an important cultural symbol for the whole region.

FASTFACTS

• Abu Dhabi’s new Zayed National Museum will open its doors to the public on Dec. 3.

• It coincides with UAE National Day, celebrated annually on Dec. 2 to mark unification.

They also serve a functional purpose, as a modern take on the barjeel wind tower, the traditional architectural device that captured breezes and directed them into buildings, cooling the interior in the days before air conditioning.

But it is through the boat, and the remarkable story of its creation, that visitors to the museum will gain a unique insight into the little-known maritime history of the ancient Arabian Gulf, and a trading network that helped the birth of civilization and the great city states of Mesopotamia.

It will also cast a light on the extent and influence of a region in Arabia known to the ancients as “Magan” — a territory that historians now believe covered an area including the modern-day UAE and Oman.

Map showing the location of foreign lands for the Mesopotamians, including Magan, an ancient region in what is now modern day Oman and United Arab Emirates. (Wikimedia Commons)

Magan was the source of the copper that was so vital to the Bronze Age — mined in the Hajar Mountains of the UAE and Oman, carried overland to the coast near modern-day Abu Dhabi city, and shipped from there to the great cities of Mesopotamia.

The vessel constructed for the museum — known as the Magan Boat — is the product of one of the most extraordinary exercises in experimental archaeology ever undertaken, its creation based on a jigsaw puzzle of archaeological evidence dating back 4,000 years or more.

The decision to build it, said Peter Magee, director of the museum, was taken “first of all because Zayed National Museum is not only a museum, it’s also a research institution. From the outset, we were keen to establish this as a place of learning and for generating knowledge.”

Archaeologists and historians, he said, “have long known about these ancient references to the boats of Magan from the third millennium B.C.E., and the museum team came up with the idea of building one as an experimental research project, to create a functional boat.”

Model of Magan boat. (Wikimedia Commons: Mohammed90m)

The result “would speak to the institution as generating knowledge and, perhaps most importantly, speak to the fact that there is a very long history of maritime engagement in this country, stretching back to the Neolithic period and certainly to the Bronze Age.”

From harvesting the first reeds that would be bundled up to create the hull to launch day in February 2024, building the boat took three years — preceded by more than a year of exhaustive research.

The project was led by Eric Staples, then a maritime historian at Zayed University, and carried out largely by a team of boatbuilders from Kerala in India.

They were chosen because they still possessed some of the dying skills required to create a boat held together by nothing more complex than palm-fiber rope and ingenious timber joints.

Experimental archeology project commissioned by Zayed National Museum, Zayed University, New York University. (Supplied)

The trail of evidence that would culminate in two days of successful sea trials in the waters off Abu Dhabi in February 2024 began in 1888, when the University of Pennsylvania dispatched an expedition to Mesopotamia — modern-day Iraq — to investigate the site of the ancient Sumerian city of Nippur, 120 km southeast of Baghdad.

Among the many treasures that were unearthed were more than 50,000 clay tablets, inscribed with cuneiform text. Buried and preserved for millennia, the tablets featured the diverse records of a lost civilization, covering everything from historical accounts, legal and administrative documents, contracts and letters, to texts on religion, grammar, mathematics and astronomy.

Among them was a tablet that detailed the exploits of a Sumerian king, Sargon the Great, who ruled between about 2334 and 2279 B.C.E. It included an intriguing line. Sargon, it was said, had “moored the ships of Meluhha, Magan and Tilmun at the quay of Agade.”

Sargon on his victory stele. The tablet, one of many treasures that were unearthed from the an the ancient Sumerian city of Nippur, 120 km southeast of Baghdad, Iraq. (Wikimedia Commons)

The precise location of Sargon’s city Agade, or Akkad, is lost to history. But in the decades since the tablet was unearthed archaeologists have pinpointed the location of the other three places it names.

Meluhha was what historians now know as the Indus Valley, home to a sprawling and advanced Bronze Age civilization that covered large parts of what is now India and Pakistan.

Magan was the land that is now occupied by Oman and the UAE, and in the cuneiform records from Mesopotamia there are multiple references to “the boats of Magan” — references that led Zayed National Museum to name its extraordinary vessel the Magan Boat.

The land of Magan co-existed with the Umm An-Nar culture, first discovered on an Abu Dhabi island of the same name in the late 1950s, and which thrived in the Bronze Age, covering an area including the UAE and Oman, between about 2500 and 2000 B.C.E.

An excavation at Al Sufouh Archaeological Site in Dubai between 1994 and 1995 revealed an Umm Al Nar type circular tomb dating between 2500 and 2000 B.C. (Wikimedia Commons)

Tilmun, or Dilmun, which emerges in the cuneiform record as an important Bronze Age trading center, was an area that included Bahrain, Qatar and parts of what today is the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia.

And it was at Dosariyah, an ancient coastal site near the modern-day city of Jubail in Saudi Arabia, that between 2010 and 2014 archaeologists unearthed some of the physical remains of the boats that had plied their trade on the Arabian Gulf thousands of years before.

The remains were fragments of bitumen, a thick, black petroleum tar that had many uses in ancient Mesopotamia and Arabia, including waterproofing the hulls of boats.

The very presence of bitumen, along with pottery from far-flung sources, was evidence of a thriving seaborne trade.

Indeed, oil “seeps” along the southern shores of the Gulf in antiquity were very scarce, and geochemical analysis of the bitumen found at Dosariyah showed that it came from sources in northern Iraq.

Traditional wooden dhow boats, each flying a Saudi flag, float peacefully on calm turquoise waters off Dammam in the Kingdom's Eastern Province. (Shutterstock photo)

But it was the imprints of ropes and reeds left on these bitumen fragments that confirmed earlier finds from elsewhere on the Arabian Peninsula, proving that boats in the Bronze Age, and even earlier, had hulls made of tightly bound bundles of reeds, stitched together over wooden frames and waterproofed with a coating of bitumen.

The 300 or more fragments found at Dosariyah echoed those from other sites — at As-Sabiyah, a pre-Bronze Age settlement in Kuwait, and at an Umm An-Nar-era site in Ras Al-Jinz, on the far eastern tip of Oman.

At these two sites, in addition to the reed-bundle impressions on one side, many of the bitumen fragments also had ancient barnacles still sticking to their outer faces — evidence that at some point in the distant past they, and the boats they had waterproofed, had been immersed in seawater for at least several months.

These finds made sense of several cuneiform texts which not only mentioned the boats of Magan, but in two cases actually listed the materials necessary for building them.

The most famous of these, known as the Girsu Tablet, is on display in the museum. The tablet, unearthed in the 19th century at the site of the Sumerian city of Girsu, 180 km northwest of Basra, is fairly small — little larger than a credit card — but packed with vital information.

The Stele of the Vultures, documented key parts of the Lagash–Umma border conflict, which took place in Sumer during the Early Dynastic III period (2600–2350 BCE), a period characterized by the division of the region into numerous city-states. (Wikimedia Commons)

The text, which appears to be a “parts list” for a major Bronze Age boatbuilding center, lists large quantities of all the materials required for building “the Magan boats under the authority of the governor of Girsu.”

The materials include five different types of timber, palm-fiber ropes, ox hides, goat hair (for sails), more than 12,000 bundles of reeds, and 500 tonnes of bitumen.

Other evidence was drawn upon to inform the distinctive shape of the Magan Boat.

The soaring “horns” of its bow and stem — created naturally by the converging of narrowing reed bundles at either end — echo the shape of model boats unearthed from ancient graves in Mesopotamia, and illustrations of Bronze Age boats found on stone and clay seals.

ALSO READ:

• How archaeological discoveries in AlUla and Khaybar are unearthing Saudi Arabia’s prehistoric past

• Archaeological survey discovers 337 new historical sites around Riyadh

• Archaeologists find ancient urban development in Baha

• Saudi Arabia’s Northern Border has 285 archaeological sites showcasing rich heritage

But it was the discovery of the telltale bitumen fragments in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Oman, and on Abu Dhabi’s own Umm An-Nar island, that provided the final pieces of evidence that informed the creation of the museum’s Magan Boat.

The discoveries at Dosariyah and As-Sabiyah, some 360 km to the southeast, added a fresh perspective on the maritime heritage of the Gulf.

In addition to echoing the finds at Ras Al-Jinz and Umm An-Nar Island, the sites in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia were dated to nearly 2,000 years before the dawn of the Bronze Age.

No one knows exactly where the Magan boats were built — whether it was somewhere in the land of Magan itself, or whether the name refers instead merely to a type of boat, the design of which probably originated in Magan.

Either way, the discovery of identical bitumen evidence at the two far earlier sites meant that the builders of Magan boats were utilizing a shipbuilding technology which, by the dawn of the Umm An-Nar culture in about 2500 B.C.E., had already been in use in the Arabian Gulf for thousands of years.

Eric Staples, head of maritime archaeology at Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism. (Supplied)

For Eric Staples, who is now head of maritime archaeology at Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism, researching, building and then sailing the Magan Boat was a successful experiment that has deepened our knowledge of the maritime history of the Arabian Gulf.

“The construction of a boat of this size is consistently referenced in the cuneiform record but had never been attempted before,” he said.

“So the fact that a boat of 120 gur (about 36 tonnes) could function as effectively as it did in our trials seems to me to validate the concept that there were vessels of this size and of this hybrid method of construction — with reed bundles, timber and bitumen — sailing the Arabian Gulf and beyond in the Bronze Age.”