JEDDAH: “Jameel Prize: Moving Images,” an exhibition of works from the finalists of last year’s Jameel Prize — an international award for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition established by the UK’s Victoria and Albert Museum — opened at Hayy Jameel in Jeddah on Nov. 19.

The works explore themes of environment, faith and community and were produced by seven artists or collectives: Sadik Kwaish Alfraji; Jawa El-Khash; Alia Farid; Zahra Malkani; Marrim Akashi Sani; the collective of Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian; and this year’s winner, Indian filmmaker Khandakar Ohida, who was awarded the prize for her work “Dream Your Museum.”

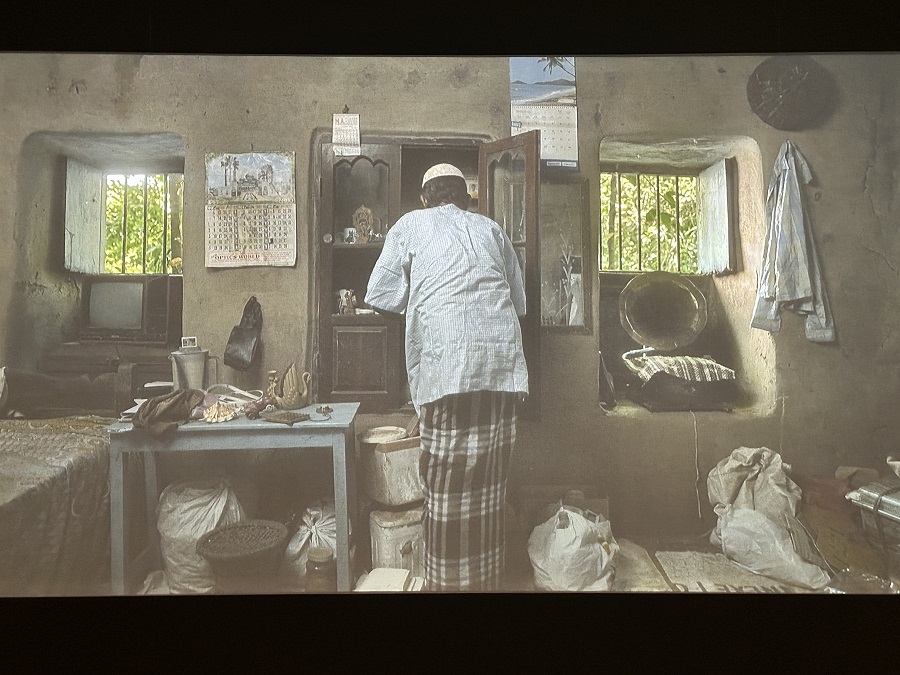

The 18-minute film is a portrait of her uncle Khandakar Selim. (Supplied)

The 18-minute film is a portrait of her uncle Khandakar Selim and the extraordinary collection of objects and memorabilia that he has built up over the last 50 years. Her uncle was a longtime ally, she explains. “I wanted to go to art school, and being a woman from a village, that was difficult. People said I should study a little and then get married. But my grandfather and uncle supported me, they said my painting was good and I should study art.”

Ohida documented the collection as it was displayed in her uncle’s traditional mud home, which no longer stands. The work invites visitors to find value in everyday objects and reflect on cultural representations and belonging.

“When someone sees my film or this installation for the first time, I hope they immediately feel a sense of connection,” Ohida tells Arab News. “The objects in the work are everyday things: stamps, train tickets, coins, gramophone parts… Many people will have seen similar items in their grandparents’ trunks. Personal stories open universal memories.”

Ohida documented the collection as it was displayed in her uncle’s traditional mud home. (Supplied)

“Dream Your Museum” emerged from Ohida’s return to her home village of Kelepara during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Since childhood, I knew my uncle collected objects. But because he collected mundane things, people called him a junk collector,” she says. “He worked as a doctor’s assistant in an eye department and used to visit many homes in Calcutta,” she says. “In every household, he asked if they were throwing anything interesting, and he collected from them. Over time, he built an entire empire of objects. He never built a concrete house because he spent everything on collecting objects. That mud house became chaotic with thousands of items, and it created family conflict,” she says.

Returning home with a new camera, she discovered that her cousin intended to discard her uncle’s collection. “In the beginning, it was like I was rescuing the objects digitally,” she explains. “My uncle spent his life being dismissed and hated for collecting, and I feel a responsibility to honor him, especially now that he is ill and has a pacemaker.”

Some of the original objects now travel with her for exhibitions; she brought a variety of them to Jeddah too. And so, the habit of collecting has been moved to another generation.

“I’m doing my residency in the Netherlands, and I find myself going to second-hand stores, buying things,” says Ohida. “So now about 10 to 15 percent of the objects are ones I collected, but 85 percent belong to my uncle. People normally throw away old objects, but uncle taught me how to rescue them.”

The scale of the archive is staggering. “I tried counting, but it’s difficult because he even collects tiny stamps, (which he counts as a single object). Roughly, it could be around 10,000 to 12,000 objects.”

The work invites visitors to find value in everyday objects and reflect on cultural representations and belonging. (Supplied)

Hardly any of the collection has ever been displayed publicly, but winning the Jameel Prize means that could soon change.

“Before, making a museum felt like a privileged, capitalist dream,” Ohida says. After the award, she told her uncle: “We will make a small space on the rooftop.” Construction is underway, and she plans to film its progress. Her uncle, she notes, has become a natural performer. “In the beginning, he was shy, but now he doesn’t care at all.”

The film has been described as “meditative.” Ohida agrees. “I think that comes from my miniature painting background,” she says. Mughal miniatures, she notes, contain “multiple stories within one frame,” and reject strict perspective.

Aside from enabling the construction of a rooftop museum, Ohida’s Jameel Prize win carried huge significance personally. “I come from a Muslim family, and it was very difficult to go to art school as a Muslim woman from a rural village,” she says. “For me, pursuing art was an act of protest. Many rural and marginalized women never get a chance to study art or culture.”

Her ambition is for the museum to become an inspiration for the children of the village. “There is no museum, no gallery, no cultural space in rural India. If even one child dreams differently, that’s enough,” she says.

She has similar ambitions for her film. “It’s not just one film; it’s an idea, a journey, a struggle, and a dream,” she says. “Others might see it and think, ‘If she did it, I can do it too.’”