LONDON: Emerging from lush woodland, amid birdsong and with wide smiles, it was a scene that could not have been further from the slaughter currently unfolding in Gaza.

Yet through the quarter of a century that has passed since the Palestinian and Israeli leaders joined President Bill Clinton for talks at Camp David, a direct line can be drawn to the daily massacres Palestinians are now facing.

What began with cautious optimism to make major headway toward a final status peace agreement ended in failure on July 25, 2000.

Clinton solemnly “concluded with regret” that after 14 days of talks, the Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat had not been able to “reach an agreement at this time.”

Israel and the US media perpetuated a myth that Arafat had turned down a generous offer of a Palestinian state. Palestinians and other diplomats involved say Israel was offering nothing of the sort.

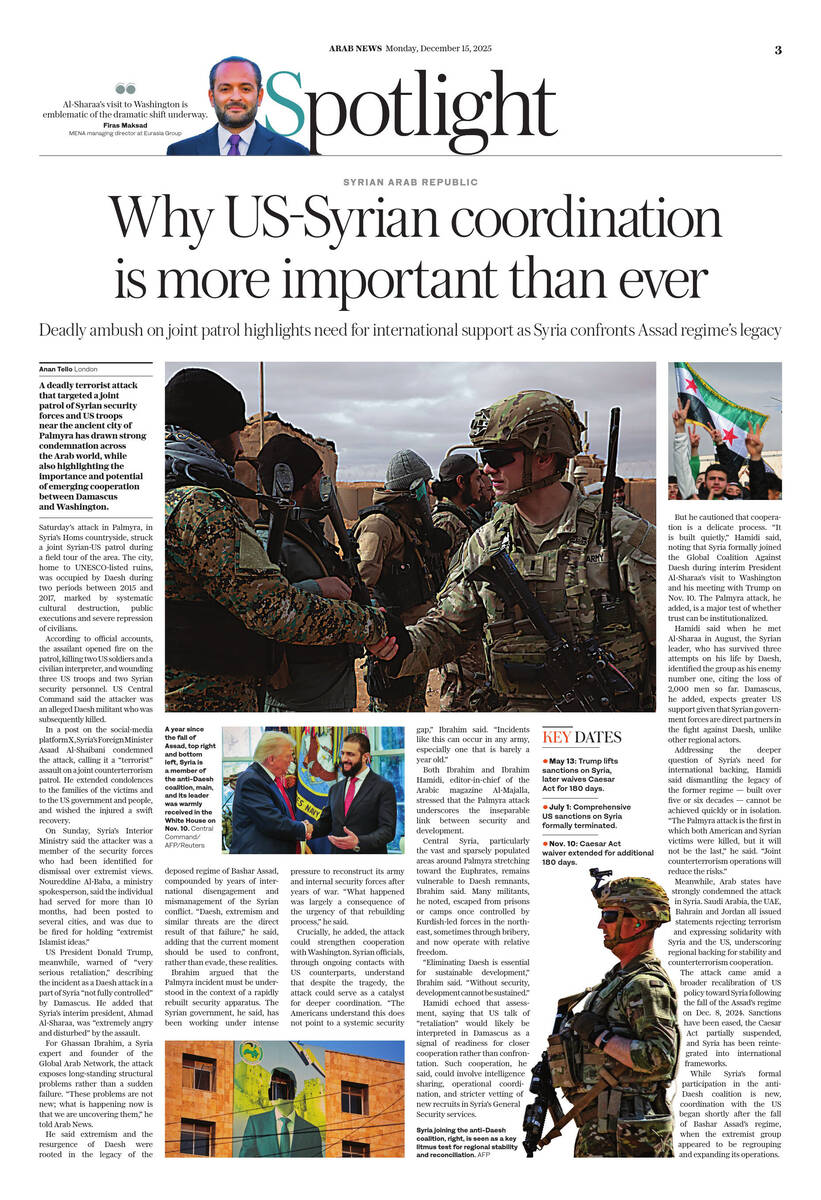

Within weeks of the talks ending, the right-wing Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon visited Haram Al-Sharif, the site of Al-Aqsa Mosque, in Jerusalem, igniting the Second Palestinian Intifada uprising against Israeli occupation.

Ariel Sharon, flanked by his security guards as he leaves the Temple Mount compound in Jerusalem on September 28, 2000. (AFP/File Photo)

While the talks have gone down in history as a failure, the six months that followed culminated in what many believe was the closest the two sides have come to a final status agreement.

But by the start of 2001, with Clinton out of office, Israeli elections looming, and violence escalating, the window of political timing slipped away.

Many were left to wonder whether the mistakes made during the Camp David meeting resulted in a missed opportunity that could have led to an agreement, thus altering the course of Middle East history.

Perhaps decades of episodes of bloodshed and occupation could have been averted.

Tents sheltering displaced Palestinians are seen amid war-damaged infrastructure in Gaza City on July 17, 2025. (AP)

With hindsight aside, is there anything that can be learned from those two weeks of negotiations that brought together the leaders from either side?

The talks at Camp David convened eight years after the first of the two Oslo Accords was famously signed in 1993 between Arafat and the then Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin at the White House.

The agreement was designed as an interim deal and the start of a process that aimed to secure a final status agreement within five years.

Under Oslo, Israel recognized the Palestinian Liberation Organization as the representative of the Palestinian people, and the Palestinian side recognized Israel.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (left) and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat shake hands on August 10, 1994 at the end of their meeting at the Erez crossing, as Shimon Peres (2nd L) looks on. After signing the Oslo Accord with Arafat, Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish extremist. (AFP/File Photo)

The agreement led to the establishment of the Palestinian Authority to have limited governance over parts of the West Bank and Gaza, which Israel had annexed in 1967 along with East Jerusalem. A phased Israeli military withdrawal from occupied Palestinian territories was also meant to take place.

By the year 2000 it was clear that the Oslo process had stalled with Palestinians deeply unhappy about the lack of progress and that the Israeli occupation had become more entrenched since the agreement. The building of Israeli settlements on occupied Palestinian land had accelerated, restrictions against Palestinians had increased, and violence continued.

Clinton, who was in the final year of his presidency, was determined to push for a blockbuster agreement to secure his legacy.

Arafat, on the other hand, was strongly against the talks taking place on the grounds that the “conditions were not yet ripe,” according to The Camp David Papers, a detailed firsthand account of the talks by Akram Hanieh, editor of Al-Ayyam newspaper and close adviser to the Palestinian leader.

“The Palestinians repeatedly warned that the Palestinian problem was too complicated to be resolved in a hastily convened summit,” Hanieh wrote.

Clinton in discussion with Arafat. (AFP/File Photo)

Barak came to the table also looking to seal a big win that would bolster his ailing governing coalition. He was looking to do away with the incremental approach of Oslo and go for an all-or nothing final agreement.

The leaders arrived on July 11 at Camp David, the 125 acre presidential retreat in the Catoctin mountains. The secluded forested location was cut off further with a ban on cell phones and just one phone line provided per delegation to avoid leaks.

It was something Clinton joked about when he greeted Arafat and Barak before the press, saying he would not take any questions as part of a media blackout.

There was even a lighthearted moment when Arafat and Barak broke into a gentle play fight as they insisted one another entered the lodge first — an image unthinkable in the current climate.

But behind the scenes there was less joviality and deep concern grew among the Palestinian camp about how the talks would unfold.

The core issues to be discussed included the extent of territory that would be included in a Palestinian state and the positioning of the borders surrounding them.

This photo released on September 28, 1995 by the White House shows Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (2nd L) and PLO leader Yasser Arafat (2nd R) are shown signing maps representing the re-deployment of Israel troops in the West Bank. Looking on are Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak (3rd L) ; US President Bill Clinton (C) ; King Hussein of Jordan (3rd R) and PLO leader Yasser Arafat (2nd R). (AFP/File Photo)

There was also the status and future of Israeli settlements, and the right of return of Palestinian refugees displaced when Israel was founded in 1948.

What proved to be the most contentious issue, and the one the US proved to be least prepared for, was the status of Jerusalem, and in particular sovereignty over its holy sites.

Palestinians want East Jerusalem to be the capital of their future state with full sovereignty over Haram Al-Sharif — the third holiest site in Islam. The site, known as the Temple Mount by Israelis, is also revered by Jews.

Because nothing was presented in writing and there was no working draft of the negotiations, there are differing versions of exactly what the Israelis proposed.

Israeli claims that Barak offered 90 percent of the West Bank along with Gaza to the Palestinians turned out to be far less when applied to maps. Israel also wanted to maintain security control over the West Bank.

Israel would annex 9 percent of the West Bank, including its major settlements there in exchange for 1 percent of Israeli territory.

Israel would keep most of East Jerusalem and only offer some form of custodianship over Haram Al-Sharif, nowhere near Palestinians demands. And there was nothing of substance on returning refugees.

Palestinian wave the Palestinians flags 11 September 1993 on the wall of Jerusalem's Old City as they celebrate the signing of mutual recognition between Israel and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) 10 September 1993. (AFP/File)

While US media interpretations of the talks often claimed the two sides were close to an agreement, Hanieh’s account describes big gaps between their positions across the major points of contention.

With a sense of foreboding of what was to come, Hanieh wrote: “The Americans immediately adopted Israel’s position on the Haram, seemingly unaware of the fact that they were toying with explosives that could ignite the Middle East and the Islamic world.”

The fact the proposals were only presented verbally through US officials meant that nothing was ever formally offered to the Palestinians.

Barak’s approach meant “there never was an Israeli offer” Robert Malley, a member of the US negotiating team, said in an article co-written a year later that sought to diffuse the blame placed on Arafat by Israel and the US for the talk’s failure.

The Israeli leader’s approach and failures over implementing Oslo led Arafat to became convinced that Israel was setting a trap to trick him into agreeing major concessions.

The Palestinians also increasingly felt the US bias toward Israel’s position, and that all the pressure was being applied to Arafat. This undermined the US as an honest broker.

A crowd of Palestinians that swarmed a building nearing the PLO headquarters in Gaza City listen to PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat's speech on July 1, 1994 after his historic return to the newly self-ruled Gaza Strip. (AFP/File Photo)

“Backed by the US, Israel negotiated in bad faith, making it impossible for Palestinians to consider these talks a foundation for a just peace,” Ramzy Baroud, the Palestinian-American editor of the Palestine Chronicle, told Arab News. “The talks were fundamentally designed to skew outcomes in Israel's favor.”

Another reason for the failure was the lack of ground work carried out before they started.

“It was not well prepared,” Yossi Mekelberg, associate fellow of the Middle East and North Africa Program at Chatham House, told Arab News. “They went there with not enough already agreed beforehand, which is very important for a summit.”

The US hosting has also been heavily criticized, even by members of its own negotiating teams.

“The Camp David summit — ill-conceived and ill-advised — should probably never have taken place,” Aaron David Miller, another senior negotiator, wrote 20 years later. He highlighted “numerous mistakes” and a poor performance by the US team that would have made blocked reaching an agreement, even if the two sides had been in a place to reach one.

Aaron David Miller, a senior negotiator for the US, wrote 20 years later that the Camp David summit was ill-conceived and ill-advised. (Supplied)

When Arafat held firm and refused to cave to pressure to accept Israel’s proposals, the summit drew to a close with little to show toward a final status agreement.

“While they were not able to bridge the gaps and reach an agreement, their negotiations were unprecedented in both scope and detail,” the final statement said.

There are various opinions on whether the talks were doomed to failure from the start or whether they can be viewed as a missed opportunity that could have brought peace to the region and averted the decades of bloodshed that followed.

The latter viewpoint stems as much from the diplomatic efforts in the months that followed Camp David.

Against a backdrop of escalating violence and during Clinton’s final months in office, focus shifted to a set of parameters for further final status negotiations. Both sides agreed to the landmark plan in late December but with reservations.

The momentum carried over to the Taba summit in Egypt three weeks later but the impending Israeli election meant they ran out of time. In the closing statement, the sides declared they had never been closer to reaching an agreement.

With the arrival of President George W Bush in office and Sharon defeating Barak in Israel’s election, political support for the process evaporated and the intifada raged on for another four years.

US President George W. Bush (R) meets with Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, 20 March 2001 in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington, DC. Sharon is on his first trip to the US as prime minister. (AFP/File Photo)

“It was a missed opportunity,” Mekelberg said of Camp David. “There was a great opportunity there, and had it succeeded, we would not be having all these terrible tragedies that we've seen.”

The way that Arafat was blamed for the failure left a particularly bitter aftertaste for Palestinians.

“The most egregious demonstration of Israel’s and the US’s bad faith was their decision to blame the talks’ collapse not on Israel’s refusal to adhere to international law, but on Yasser Arafat’s alleged stubbornness and disinterest in peace,” Baroud said.

The talks were “unequivocally doomed to failure,” he said because they rested on the false premise that the Oslo Accords were ever a genuine path to peace.

“The exponential growth of illegal settlements, the persistent failure to address core issues, escalating Israeli violence, and the continuous disregard for international principles concerning Palestinian rights all contributed to Camp David’s collapse.”

He said if any lessons are to be taken by those attempting to negotiate an end to Israel’s war on Gaza and implement a wider peace agreement, it would be that “neither Israel nor the US can be trusted to chart a path to peace without a firm framework rooted in international and humanitarian law.”

In the coming days, Saudi Arabia and France will co-chair a conference at the UN on the two-state solution to the conflict, that seeks to plot a course toward a Palestinian state. Perhaps this could help build the sustainable international framework that was lacking in July 2000.