DHAHRAN: For the finale of the two-day Sync Digital Wellbeing Summit at the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, or Ithra, a documentary titled “The Dark Side of Japan” premiered at the Ithra Cinema on Thursday.

The Bahraini creative influencer, Omar Farooq, who was the narrator in the documentary, was there in-person with his team to answer questions after the screening.

As part of the Sync Spotlight series, the documentary tied together all the various themes explored during the summit, of which technology and wellness topics were explored on stage and at various points throughout the center. The documentary, which was filmed in Japan, showcases Farooq as he observes the Japanese people’s intense interactions with — and addictions to — their screens. Amid the bright lights of flashy Tokyo emerges a lingering dark side of loneliness, heads down, and fingers scrolling endlessly.

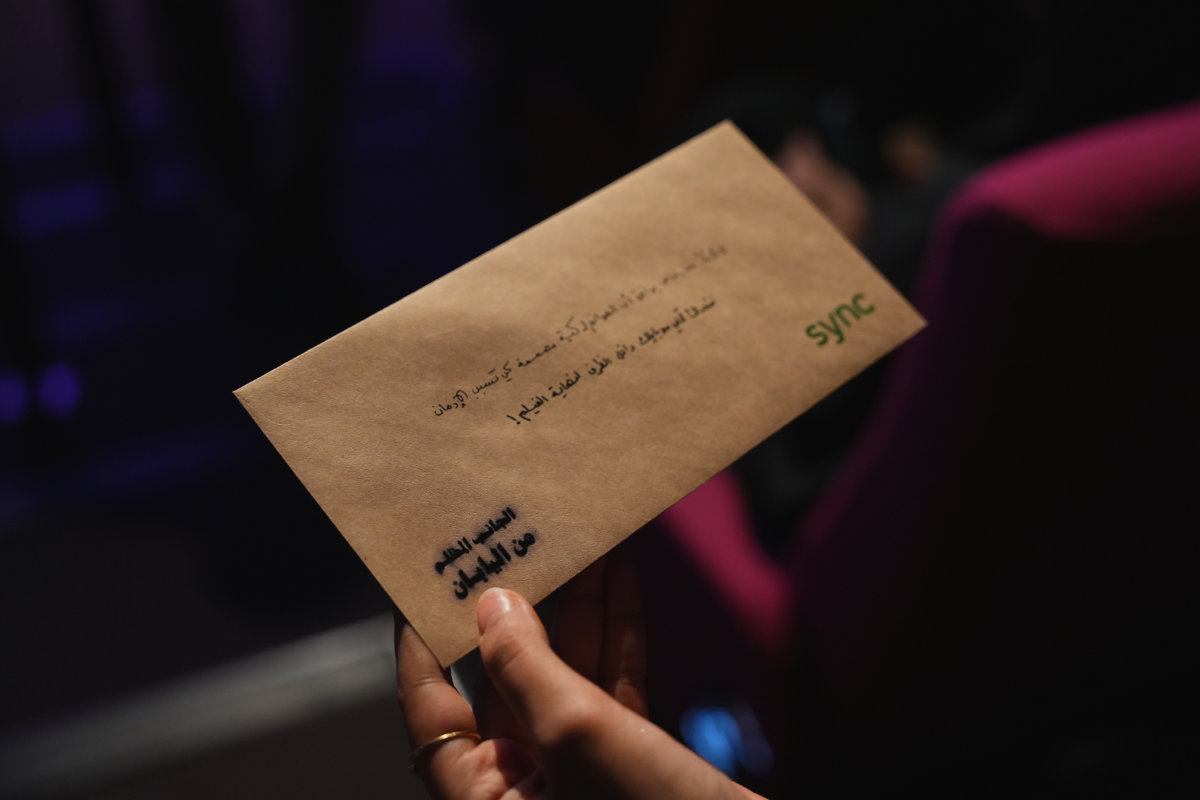

The filmmaker and influencer tried to convey an important message the old-fashioned way before the film premiere. He asked every attendee to take a moment to look under their seats. After a minute of awkward shuffling, it was revealed that an envelope was placed there so they could tuck their phones away and watch the documentary phone-free.

An envelope that was placed under each seat at the Ithra Cinema instructing viewers to place their phones there and enjoy the documentary phone-free. (Supplied)

Farooq wanted the audience to be completely immersed and to be on the journey alongside him.

The documentary takes viewers on a trip as he journeys to places near and far within Japan to interact with locals, expats and visitors about their relationship to technology and nature. He spoke to families of young children about the school system and he spent time with adults of various backgrounds to ask about their preferences: city life or country life?

“It’s hard to keep a close relationship with people (in Tokyo). We don’t have time to care about others,” a Japanese artist told him in one scene.

Wildly popular, with 3.9 million followers on instagram, Farooq was on hand to have a discussion on stage after the screening. Moderated by Ithra’s own head of a performing arts and cinema, Majed Z. Samman, who had studied in Japan and was familiar with the Japanese culture, they were joined by Mohammed Alhajri and Ahmed Alsayed, both of whom were with Farooq in Japan to assist with the filming. They sat on the floor, Japanese style, on stage for the discussion.

The panel sat on the floor, Japanese style, for the panel discussion. (Supplied)

“This documentary isn’t about Japan,” Farooq cautioned the audience. Japan was merely an example of a place that has been plagued by hyper internet addiction and loss of real world connection. He asks the question: “Will this be our future? Is it already our present?”

He instructs viewers to look within and not just walk away as a programmed robot on autopilot; constantly shackled to their smartphones and ignoring the world around them.

After the initial screening, there were two other screenings back-to-back at the cinema, both of which were sold out.

The Ithra-produced documentary was mostly in Arabic, with some English and some Japanese.