LAHORE: For Saad Mehmood, it was a routine visit to a mosque in the eastern Pakistani city of Lahore for Friday prayers in 2017 when the then 22-year-old stumbled upon a store room with sheaves of paper stored carefully on a shelf.

The worn pages were fragments from everyday copies of the Qur’an, which were awaiting ritual disposal. In Pakistan, pages of the holy book that are disposed are often called shaheed, or martyred, copies.

In Islam, widely accepted methods of disposing worn pages of the holy book are to wrap them in a cloth and bury them, ideally in a mosque, or to burn them respectfully.

But Mehmood, at the time a final year student of fine arts at the Beaconhouse National University (BNU), was inspired by the worn copies and decided to restore them as part of his thesis.

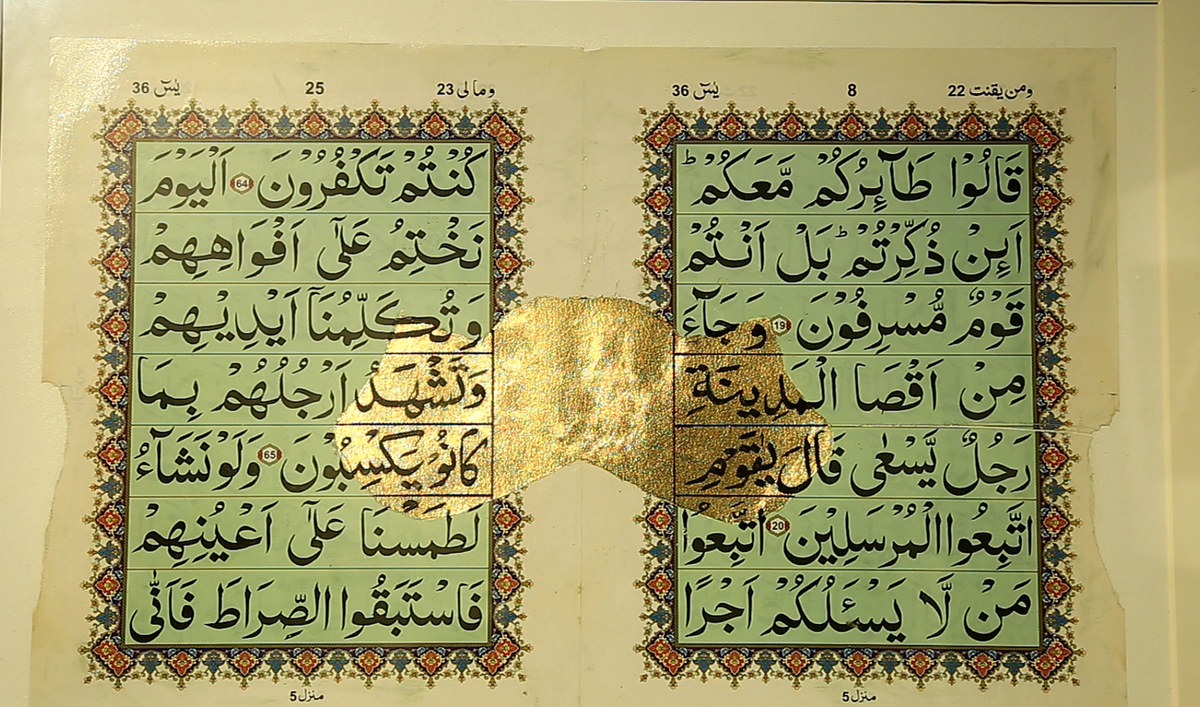

“Saad asked for some of these pages that were torn or worn out, and started to restore the ordinary, mass-printed sheets with gold paper and the finest ink — bringing that which was ‘martyred’ back to life,” the artist’s statement accompanying an ongoing exhibition of his works in Lahore reads.

The effort is “an act of artistic devotion,” Mehmood told Arab News at the exhibition last week, saying all his work now revolved around restoring the holy pages and turning them into artforms.

“This work started in 2017,” Mehmood, now a 28-year-old visual artist, said. “I collect the pages of the Qur’an that are shaheed, then there’s an entire process to their restoration, I fill in the damaged parts so that the pages are readable again.”

Pakistani artist Saad Mehmood, 28, speaks to a visitor during his exhibition in Lahore on March 23, 2024. Mehmood’s work aims to restore worn Qur’anic pages ready for ritual disposal. (AN Photo)

Mehmood said he had done extensive research on damaged Qur’anic pages and what happened to them and where they went from storerooms of mosques and homes.

“I saw that they’re buried in graveyards, or floated in clean and flowing water. Sometimes, I even saw the pages being burned and their ashes buried in some corner of a graveyard,” he explained.

This got Mehmood thinking: instead of disposing of the sacred texts, he could restore them.

The process of restoration was a difficult one, as many Qur’an pages Mehmood came across had no references.

“When we open these [Qur’anic] collections… there are [some] smaller pages which don’t have any references [which ayat, surah, what page number],” he said. “So, this was a conundrum… how do I restore them when there’s no reference to work with?“

Mehmood decided to make a collage of such pages.

“So, at least they are still visible, still accessible,” he said. “So, we don’t accidentally disrespect the words, they will remain in front of our eyes, and then turn them into art to be appreciated.”

Mehmood has also visited multiple religious scholars to present his idea and his work.

“There are a lot of organizations in Pakistan like Tahaffuz-e-Auraq [who dispose of pages in the prescribed manner],” Mehmood said. “I restored them and then I started showing people that basically this is the work I’m doing.”

The idea found wide acceptability, he said.

“GOLD LEAF”

The ongoing exhibition in Lahore, organized by the Pakistan Art Forum, includes collages of restored Qur’anic fragments, concentric circles around Islamic calligraphy, decorative additions like gold leaves, and paintings with Arabic diacritics on Vasli and white paper. And this is all by design.

Mehmood said he wants to further explore this Islamic art form and create something new, like his painting of the diacritics without any words, or of punctuation marks without any sentences.

“The Qur’an came to us from Arabia, and the diacritics were added later, so that non-native Arabic speakers [Ajmi] could understand the text,” he said. “[Helping] in how to pronounce and enunciate it, zeir, zabr, that is also something I’ve worked on, and will continue to work on.”

There is also a reason why Mehmood uses gold leaf so often.

This photograph taken on March 23, 2024 shows an art piece by Pakistani artist Saad Mehmood, 28, in Lahore. Mehmood’s work aims to restore worn Qur’anic pages ready for ritual disposal. (AN Photo)

“When you look at my work… I have used gold leaf on the shaheed [damaged] Qur’anic pages,” he said.

“I used that gold leaf specifically and consciously, because gold is considered a divine material. And where the words are missing, pages torn, I’ve also used gold leaf to show the preciousness of the lost words, using a precious material.”

“EXPAND WAYS TO EXPERIENCE QUR’AN”

The visual artist has held a number of group exhibitions at the Alhamra Arts Center in Lahore and Sanat Gallery in the southern port city of Karachi. Last week, he held his second solo show in Lahore, titled Al-Qadr, referring to the night when Muslims believe the Qur’an was first revealed.

While most of the visitors to the Lahore exhibition said they had come out of curiosity, they left with admiration for the intricate work and beautiful calligraphy or collage technique that Mehmood uses.

“Calligraphy is a part of [what I do], but this is something else [entirely],” he explained. “You can call it a collage. You can call it an installation. You can call it painting, you can call it artwork.”

Shahid Rassam, a famous Pakistani painter and sculptor, described Mehmood work as “positive,” saying he had seen other works, though rare, in which worn Qur’an pages were restored as a form of art.

Rassam, who has himself made contemporary forms of the Qur’an, including one in which he used metal engravings, said it was “vital to expand the ways in which we experience the sacred text, even as art installations.”

“I think what this young man [Saad Mehmood] is doing is objectively a positive thing,” the artist said. “He’s taking sacred pages and giving them their rightful respect, instead of just letting them lie in poorly-kept stores and boxes.”

Visitors attend an art exhibition by Pakistani artist Saad Mehmood, 28, in Lahore on March 23, 2024. Mehmood’s work aims to restore worn Qur’anic pages ready for ritual disposal. (AN Photo)