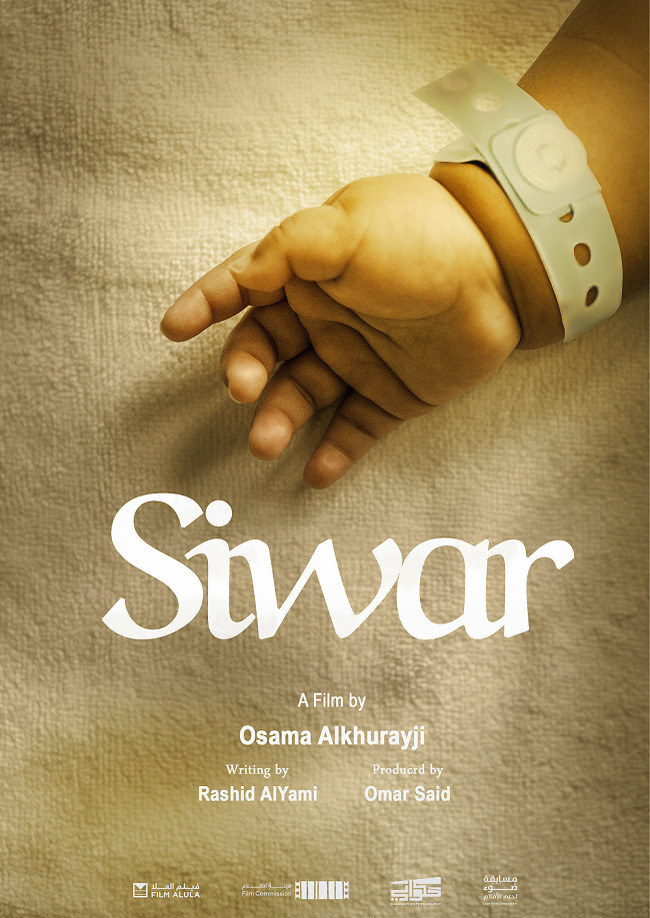

ALULA: The debut feature-length film by award-winning Saudi director and producer Osama Alkhurayji, “Siwar,” will be filmed in AlUla, Film AlUla, the Royal Commission for AlUla’s film agency, announced on Wednesday.

With Film AlUla providing rebates and incentives to promote and enable homegrown filmmakers, the announcement is closely aligned with the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 goals to diversify the economy and foster cultural development, according to a media release.

“Siwar” is a heart-rending narrative of two families entangled in a fateful revelation about their newborns. The film, spanning three chapters, delves into the lives of Yaner, a Turkish father, and Hamad, a Saudi father, as they navigate societal challenges and personal upheavals.

This storytelling approach reflects Alkhurayji’s unique ability to craft engaging narratives that resonate with audiences on multiple levels.

In addition to his role as the director of “Siwar,” Alkhurayji began his filmmaking journey in 2007, earning international recognition for his work. A prolific content producer, he has worked with several regional and international TV networks, theaters, distributors, and streaming platforms such as Netflix, Shahid and SBA.

“‘Siwar’ is poised to make a profound impact at both national and international levels, reflecting the unique stories and cultural richness of the region. Stay tuned for more updates on this exciting project,” said Alkhurayji.

The film is produced by Omar Said, whose credits span work across Los Angeles, Vietnam, Mexico, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia.

He said: “Since 2016, I’ve been immersed in Saudi Arabia’s thriving film industry, watching it flourish daily. I’m thrilled about sharing our upcoming story — the excitement to captivate audiences is beyond words.”

Meanwhile, Charlene Deleon-Jones, executive director of Film AlUla, said: “Over the past three years, Film AlUla has steadily and sustainably built a film economy that can host high-quality film production. It is a privilege and of primary importance to support homegrown talent. AlUla, with its history of storytelling, is a perfect place to platform new talent. We are thrilled to be supporting Alkhurayji for his film ‘Siwar’.”

“Siwar” comes close on the heels of two other high-profile Saudi productions to be shot in AlUla — Netflix drama “The Matchmaker” and Saudi filmmaker Tawfik Al-Zaidi’s debut feature “Norah,” which premiered at the Red Sea International Film Festival this year. “Norah” is the first local feature film to be shot in AlUla and features an all-Saudi cast and more than 40 percent Saudi crew.

The expanding roster of Saudi productions reinforces Film AlUla’s ambition to expand the opportunities and reach available to homegrown creators.

Film AlUla unveils ‘Siwar,’ a venture with Hakawati entertainment

https://arab.news/bpsc7

Film AlUla unveils ‘Siwar,’ a venture with Hakawati entertainment

- Announcement is closely aligned with Vision 2030 goals to diversify economy and foster cultural development

- ‘Siwar’ comes close on the heels of 2 other high-profile Saudi productions to be shot in AlUla

Decoding villains at an Emirates LitFest panel in Dubai

DUBAI: At this year’s Emirates Airline Festival of Literature in Dubai, a panel on Saturday titled “The Monster Next Door,” moderated by Shane McGinley, posed a question for the ages: Are villains born or made?

Novelists Annabel Kantaria, Louise Candlish and Ruth Ware, joined by a packed audience, dissected the craft of creating morally ambiguous characters alongside the social science that informs them. “A pure villain,” said Ware, “is chilling to construct … The remorselessness unsettles you — How do you build someone who cannot imagine another’s pain?”

Candlish described character-building as a gradual process of “layering over several edits” until a figure feels human. “You have to build the flesh on the bone or they will remain caricatures,” she added.

The debate moved quickly to the nature-versus-nurture debate. “Do you believe that people are born evil?” asked McGinley, prompting both laughter and loud sighs.

Candlish confessed a failed attempt to write a Tom Ripley–style antihero: “I spent the whole time coming up with reasons why my characters do this … It wasn’t really their fault,” she said, explaining that even when she tried to excise conscience, her character kept expressing “moral scruples” and second thoughts.

“You inevitably fold parts of yourself into your creations,” said Ware. “The spark that makes it come alive is often the little bit of you in there.”

Panelists likened character creation to Frankenstein work. “You take the irritating habit of that co‑worker, the weird couple you saw in a restaurant, bits of friends and enemies, and stitch them together,” said Ware.

But real-world perspective reframed the literary exercise in stark terms. Kantaria recounted teaching a prison writing class and quoting the facility director, who told her, “It’s not full of monsters. It’s normal people who made a bad decision.” She recalled being struck that many inmates were “one silly decision” away from the crimes that put them behind bars. “Any one of us could be one decision away from jail time,” she said.

The panelists also turned to scientific findings through the discussion. Ware cited infant studies showing babies prefer helpers to hinderers in puppet shows, suggesting “we are born with a natural propensity to be attracted to good.”

Candlish referenced twin studies and research on narrative: People who can form a coherent story about trauma often “have much better outcomes,” she explained.

“Both things will end up being super, super neat,” she said of genes and upbringing, before turning to the redemptive power of storytelling: “When we can make sense of what happened to us, we cope better.”

As the session closed, McGinley steered the panel away from tidy answers. Villainy, the authors agreed, is rarely the product of an immutable core; more often, it is assembled from ordinary impulses, missteps and circumstances. For writers like Kantaria, Candlish and Ware, the task is not to excuse cruelty but “to understand the fragile architecture that holds it together,” and to ask readers to inhabit uncomfortable but necessary perspectives.