ISLAMABAD: Pakistan’s permanent representative to the United Nations and envoys from the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) members have called on the UN Secretary-General António Guterres, where they stressed the need to outlaw “deliberate acts of provocation” like the desecration of the Holy Qur’an, Pakistan’s UN mission said on Saturday.

The development came after an Iraqi immigrant, Salwan Momika, who burned the Qur’an outside a Stockholm mosque last month, once again desecrated the holy book on Thursday by stomping on it in a two-man rally outside the Iraqi embassy in Stockholm.

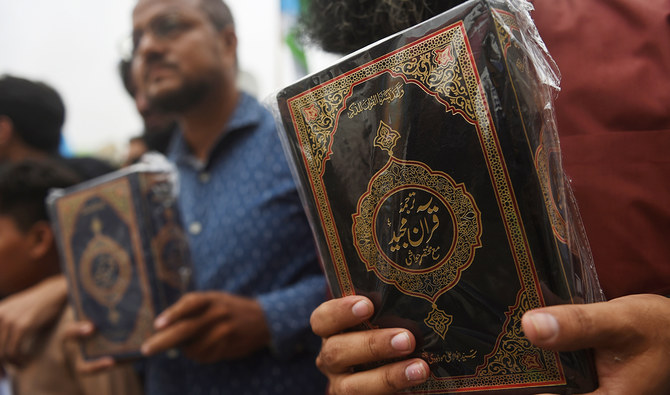

Muslim-majority nations across the world expressed their outrage on Friday at the desecration of the Qur’an in Sweden, with hundreds of thousands attending street demonstrations following midday prayers to show their anger over the incident.

Ambassador Munir Akram, Pakistan’s permanent representative, together with envoys from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bangladesh and Mauritania called on the UN chief to condemn the recurring act of desecration of the holy book.

“Ambassador Akram conveyed to the Secretary General that the Parliament of Pakistan has recently adopted a Resolution condemning the despicable act of desecration of the Holy Qur’an in Sweden and handed over a copy of the Resolution,” Pakistan’s UN mission said in a statement.

“He also underlined the need for those countries, in the light of the Resolution recently adopted by the Human Rights Council on the issue, to outlaw the deliberate acts of provocation such as burning of the Holy Qur’an, which can lead to violence.”

Activists of the right-wing religious Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) party hold copies of the Koran during an anti-Sweden demonstration in Karachi on July 5, 2023, following the burning of the Koran outside a Stockholm mosque that outraged Muslims around the world. (AFP)

The OIC wished for Guterres to adopt a plan of action against Islamophobia, the Pakistani permanent representative conveyed.

The UN secretary-general referred to the acts of desecration of the Holy Qur’an as “condemnable” and agreed that the resolution adopted by the UN Human Rights Council should be implemented by all members states, according to the statement.

The resolution, adopted this month, urged countries to “address, prevent and prosecute acts and advocacy of religious hatred” after incidents of Qur’an-burning in Sweden. It was strongly opposed by the US, European Union (EU) and other western countries, which argued that it conflicted with laws on free speech.

Later, the OIC group met Security Council President Ambassador Barbara Woodward to convey the OIC’s concerns over the “despicable” act.