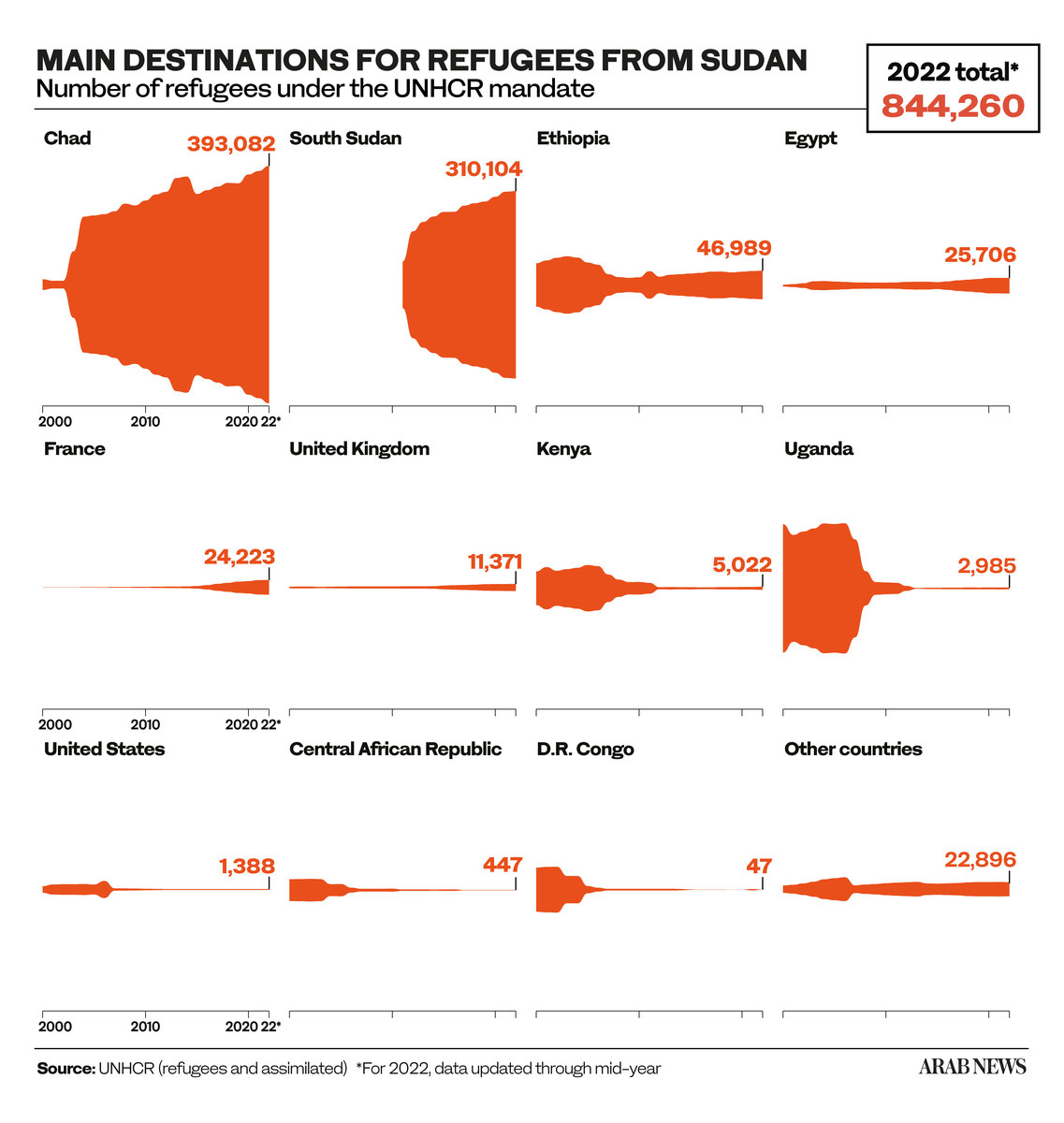

JUBA, South Sudan: Over the past two years, the world has been plagued by large-scale refugee crises, from Syria and Afghanistan to Ukraine and Myanmar. Last year, the UN estimated that over 100 million people worldwide were displaced. Now, the conflict between rival military factions in Sudan which began last month may see these numbers swell even further.

As of Tuesday — just over three weeks since deadly clashes broke out between Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan’s Sudanese Armed Forces and Mohamed Dagalo’s Rapid Support Forces militia — more than 100,000 people had poured into neighboring countries from Sudan in search of safety, according to the UN.

Kak Ruot Wakow, a peace-building coordinator for an NGO, recently fled from Khartoum on his employer’s vehicle and is currently staying in Paloch, a town in South Sudan’s Upper Nile state that has become a way station of sorts for people displaced by the fighting in Sudan.

“I didn’t see bodies, but I saw damaged tanks on the road. At the time I left Khartoum, the clashes were occurring not in all parts of the city but at the military bases,” he told Arab News from Paloch. Along the way, Ruot Wakow came across units of the Rapid Support Forces who fortunately allowed him to pass through.

He said in addition to South Sudanese, there were Ethiopians, Eritreans, Kenyans, Somalis, Congolese and Ugandans in the human tide moving in the direction of the Sudan-North Sudan border.

Sudanese refugees from the Tandelti area who crossed into Chad are seen on April 30, 2023. (AFP)

Similar events are unfolding at other exit points around Sudan. The scene in Port Sudan, a city in the east currently being swarmed by both Sudanese and foreign nationals looking for passage on a ship to Saudi Arabia and beyond, is a grim one. Thousands wait for days under tents in temperatures exceeding 40C, not knowing when, or if, they will manage to make it out of the country.

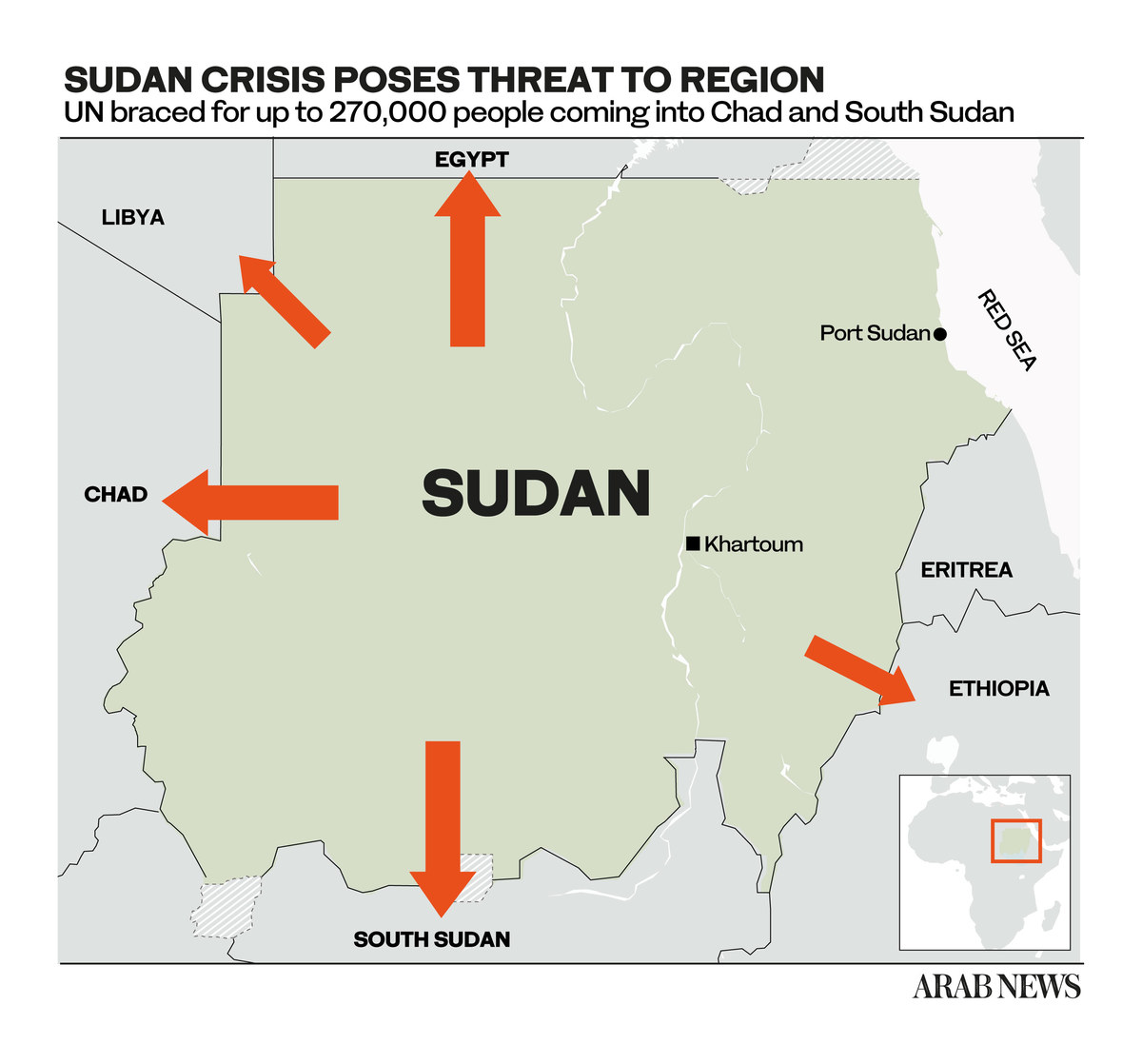

According to a member-state briefing in Geneva on Monday by UN Assistant High Commissioner for Refugees Raouf Mazou, the UN estimates that as many as 580,000 Sudanese may flee into South Sudan, Chad, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, the Central African Republic and even into war-torn Libya.

At the end of last month, Sudanese nationals attempting to enter Egypt told the UK’s Guardian newspaper about chaotic scenes at the border, with immigration officials attempting to process the new arrivals who waited in the open air with little food and water.

Last week, Pierre Honnorat, director of the UN World Food Programme in Chad, told Reuters news agency that tens of thousands of Sudanese had crossed into the country to Sudan’s west, and that the WFP expected more waves to arrive as the conflict escalates.

Thousands of Sudanese have flooded Chad’s eastern border villages, often outnumbering local villagers, and finding no shelter and little in the way of food or water.

Provision of water, sanitation and hygiene to a growing number of IDPs have become an alarming issue. (AN photo by Robert Bociaga)

The emerging humanitarian crisis is compounded by Sudan’s already large refugee burden. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees or UNHCR, Sudan hosts more than a million refugees and is home to over 3 million internally displaced persons (IDPs).

A large number of those fleeing south are actually experiencing a second displacement back to their country of origin: UN statistics show that 800,000 South Sudanese refugees live in Sudan.

The return of tens of thousands of them to South Sudan is raising the specter of a humanitarian disaster. Last year, South Sudan’s Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management reported that 1.6 million of the country’s 11.7 million population belonged to the category of IDPs.

Jebel IDP camp: With approximately 1.6 South Sudanese being internally displaced, the fighting in Sudan only aggravates the situation. (AN photo by Robert Bociaga)

The UNHCR has mobilized resources to assist those who have fled Sudan, including an estimated 9,000 Sudanese nationals who have arrived in South Sudan’s Renk county alone. The South Sudanese government has also deployed personnel to the Sudan border to receive fleeing citizens.

According to Maj. Gen. Charles Machieng Kuol, secretary of South Sudan’s Joint Defense Board, the northern region of South Sudan is the most affected, with a majority of the new arrivals heading to the country’s capital, Juba. “Most of (the) displaced are heading to Juba, by road, air or water,” he told Arab News.

Ruot Wakow, the NGO employee, said many South Sudanese were traveling to Sudan’s White Nile state by bus before embarking on the journey to South Sudan. According to him, the local community does not have the capacity to help the population in transit as the numbers are huge and impossible to monitor.

Currently, repatriation of South Sudanese along this route is happening in two batches every day, which is not enough, Ruot Wakow said. “People mostly want to go to Juba as this is the only corridor to reach other places. The risk rises if one travels by boat owing to the lack of security.”

Although the South Sudanese government has allocated a sum of money equivalent to $7.6 million to assist those returning from Sudan, thousands of returnees are still stranded in northern Upper Nile, lacking access to basic necessities.

Catastrophic floods in South Sudan make the movement of people fleeing the conflict much harder. (AN photo by Robert Bociaga)

“On the ground, I did not see any support except from IOM (International Organization for Migration) and UNHCR, who provided some buses and ferries to evacuate people from the South Sudan border to Paloch,” Ruot Wakow said.

He said the new arrivals complained of lack of proper shelter and disease. “There are now some cases of cholera because of sanitation issues and the heavy rains. The accommodation situation is horrible,” he said.

Indeed, those lucky enough to make it to South Sudan quickly realize that they face a new set of hardships, including a lack of access to basic necessities such as food, water and shelter. The massive influx is putting a strain on resources and infrastructure, prompting some recent arrivals to move across another border to Uganda.

“People are moving from here to Uganda because of the difficulties that are facing them,” Kam William, an IDP from South Sudan’s northern region, told Arab News. “The World Food Programme has stopped supplying here in Juba, so there is no food. There is nothing; it is actually very difficult. Here, there is no money.”

The situation is made even more difficult by prolonged flooding in large parts of South Sudan. The natural disaster has forced hundreds of thousands of people from their homes, making it even more challenging for aid organizations to provide assistance to those in need.

“I got here when the war broke out in Bentiu. I came by boat,” Christ Yoany Kuany, a pastoralist who fled to Juba, told Arab News. “Life there is very difficult. The area has experienced very heavy flooding for the last three years. I lost 100 cows in Bentiu. All the remaining cows died of diseases.”

In some cases, communities have clashed over access to resources, leading to violence and displacement. The situation is particularly difficult in areas where the government and aid organizations have limited access, which makes it harder to provide support and assistance to those affected by the violence.

The fighting in Sudan also has the potential to contribute to existing inter-communal tensions in South Sudan. Some of the people fleeing Sudan are likely to bring with them longstanding ethnic and political rivalries, which could fuel conflicts in their new communities.

“This is our home, our country,” James Deng, a South Sudanese currently living in an IDP camp in Juba’s Jebel area, told Arab News. “And yet, we have nowhere to go. Here, we have so many diseases.”

The situation is particularly dire in Juba’s Mangateen IDP camp, which has been submerged by heavy rains, leaving thousands of displaced people without shelter or access to basic necessities. The lack of resources and support has left many people vulnerable to disease, malnutrition and other health risks.

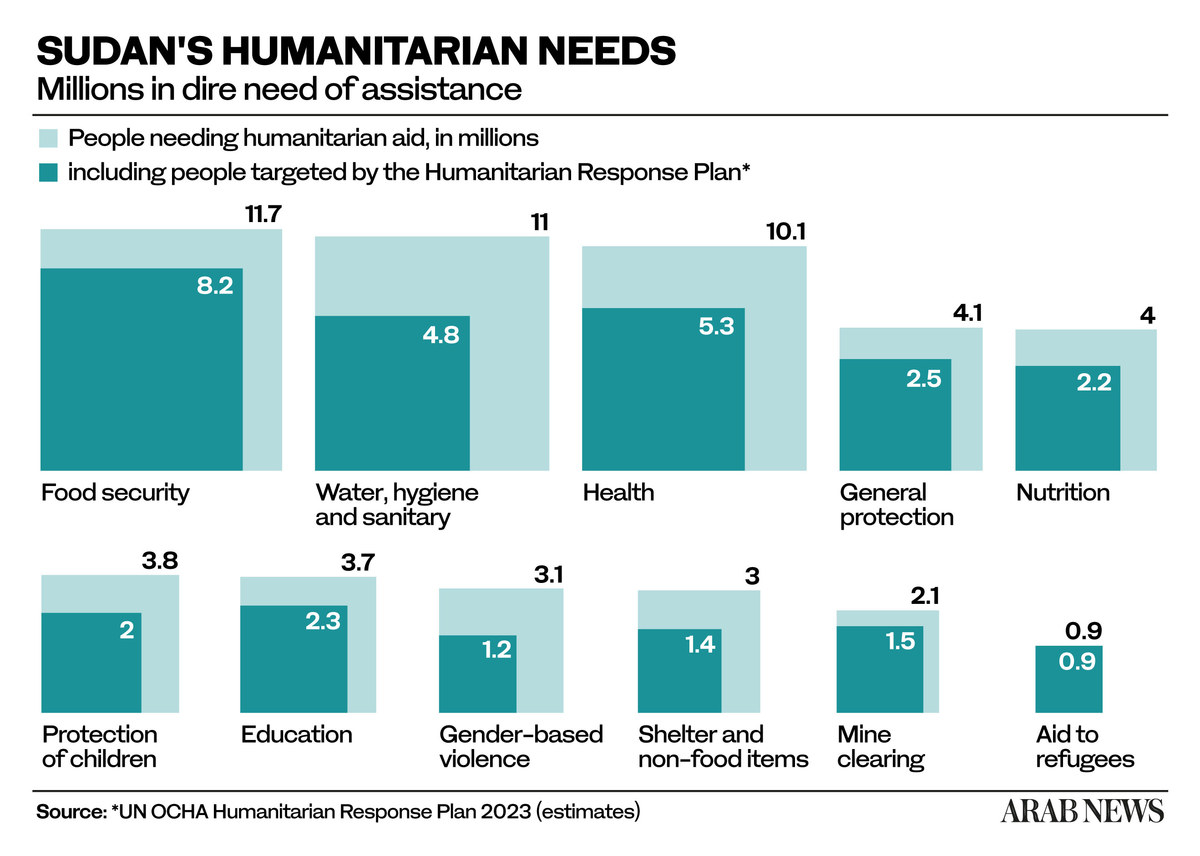

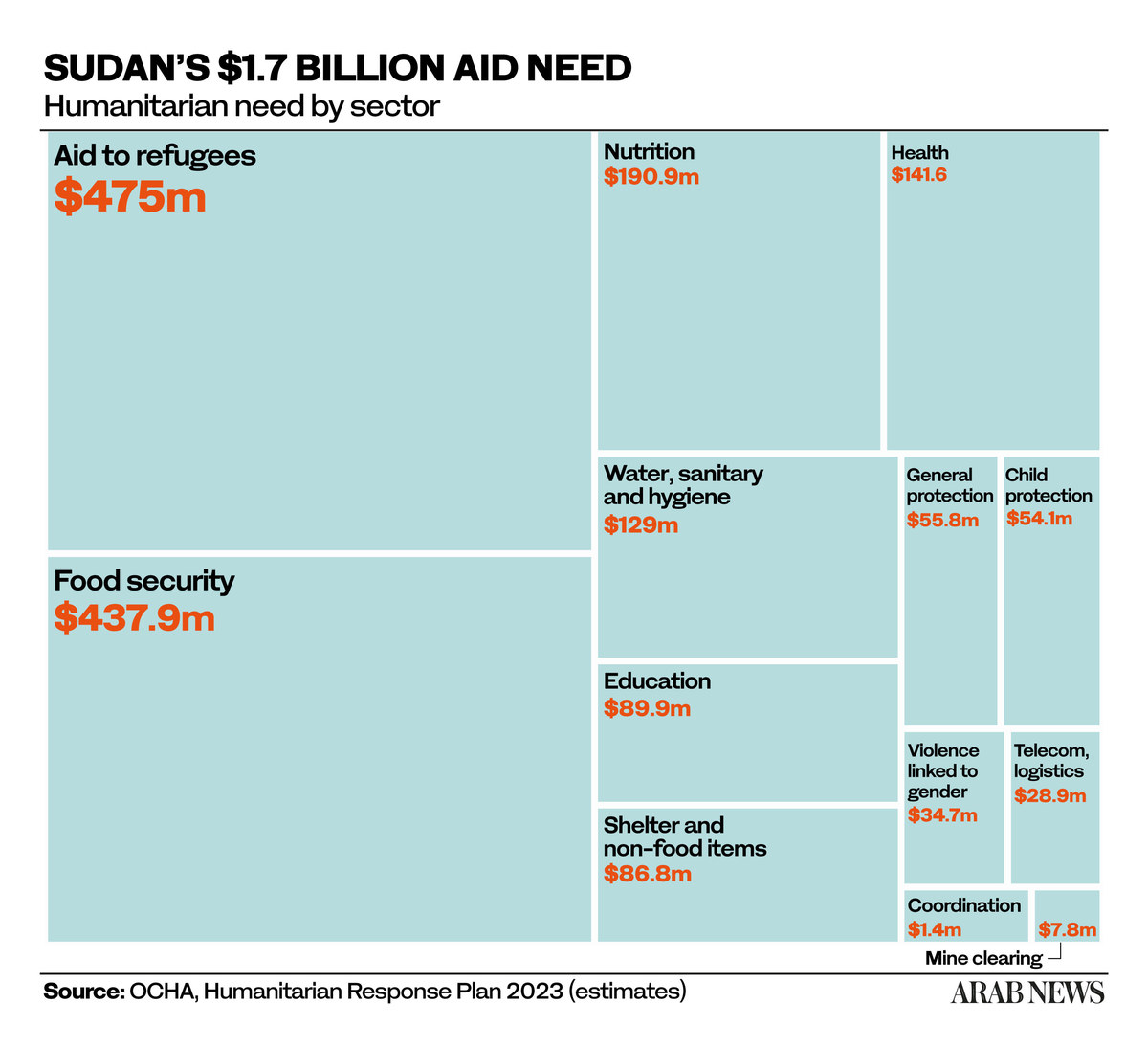

The situation in South Sudan will definitely get worse if the flow of people out of Sudan turns into a human tide. Abdou Dieng, the UN’s acting resident and humanitarian coordinator in Sudan, gave warning on Monday that millions of Sudanese are in need of immediate assistance and millions more are confined to their homes, unable to access basic necessities.

Many health facilities have been forced to close while those that are still operating face challenges, including shortages of medical supplies and blood stocks, he added.

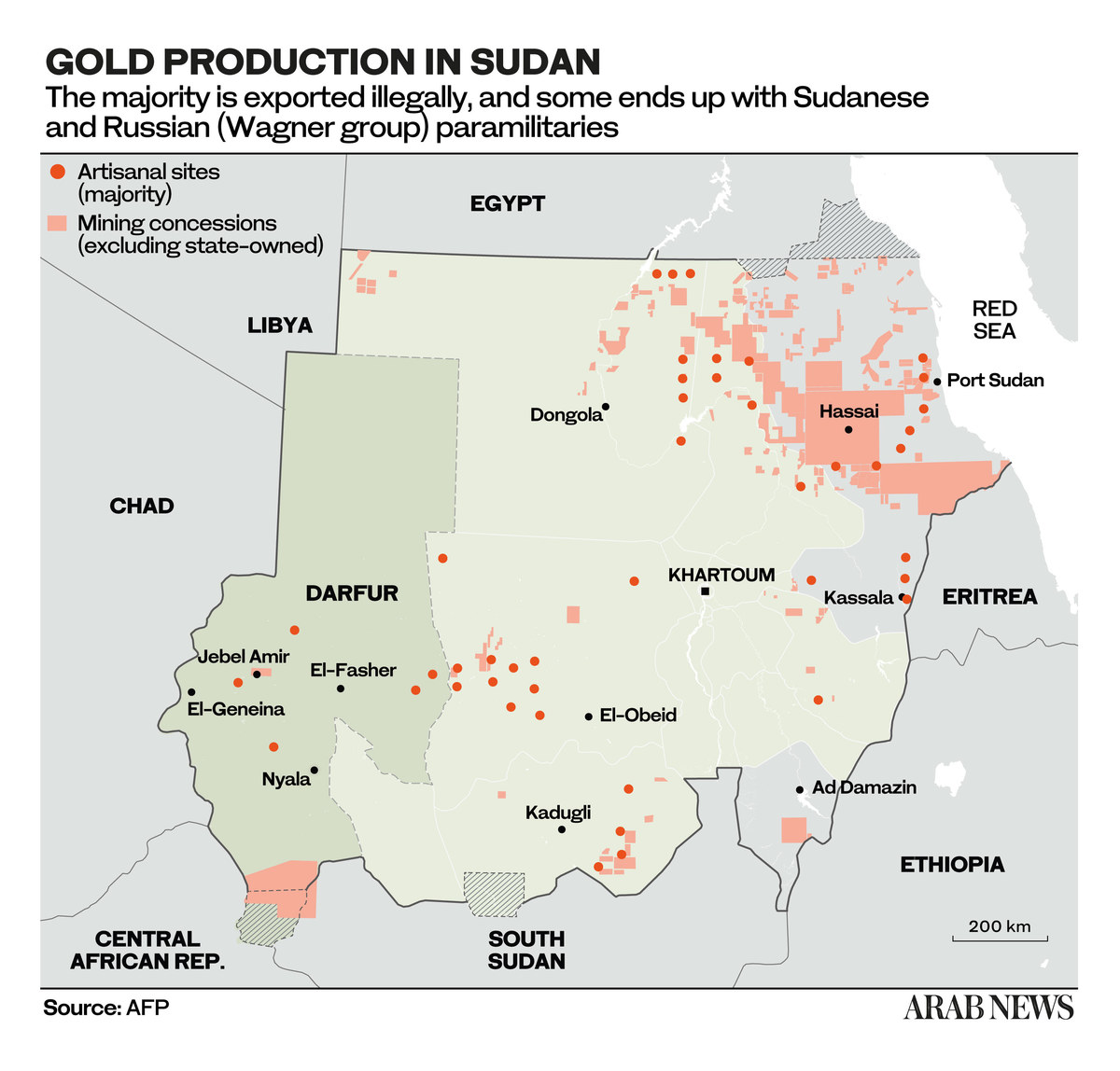

Officials from the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs said 16 million people in Sudan, a third of the population, are in need of assistance, and 3.7 million, mainly from Darfur province, have been displaced from their homes since the fighting began on April 15.