KHARTOUM: Sixteen months since Sudan’s top generals ousted a transition to civilian rule, the coup leaders are embroiled in a dangerous power struggle with deepening rivalries within the security forces, analysts warn.

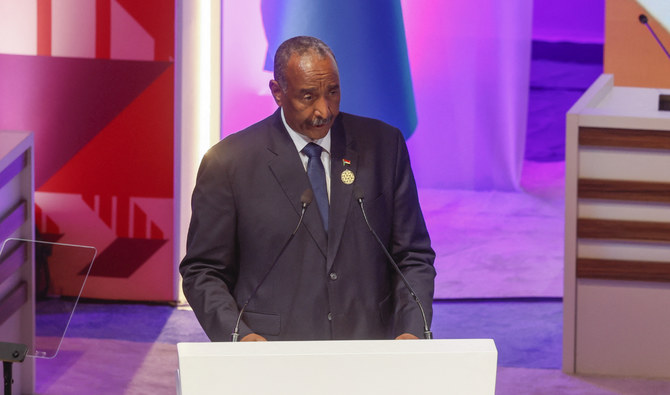

Army chief Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan and his deputy Mohamed Hamdan Daglo worked together in October 2021 to remove the short-lived transitional authorities put in place following the toppling of Omar Bashir’s regime in 2019.

Magdi Al-Gizouli, from the Rift Valley Institute think tank, said their once united front has devolved into “brinkmanship.”

“The power struggle in Sudan is no longer between military and civilians,” Gizouli said. “It is now Burhan against Daglo, each with his own alliance.”

The coup triggered international aid cuts and sparked near-weekly protests, adding to the deepening political and economic troubles of one of the world’s poorest countries.

Burhan, a career soldier from northern Sudan who rose the ranks under the three-decade rule of now jailed general Bashir, has said the coup was “necessary” to include more factions into politics.

But Daglo, also known as Hemeti, the commander of the much-feared paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, has since called the coup a “mistake.”

Created in 2013, the RSF force emerged from the Janjaweed militia that Bashir unleashed a decade earlier in the western region of Darfur against non-Arab rebels, where it was accused of war crimes by rights groups.

Daglo — from Darfur’s pastoralist camel-herding Arab Rizeigat people — said the coup had not brought change but rather the return of Bashir-era regime loyalists, angering religious factions.

Disagreements between the two generals also reflect long-running divisions between the regular army and Daglo’s RSF, said military expert Amin Ismail.

“Burhan wants the RSF to be integrated into the army in accordance with the rules and regulations within the army,” said Gizouli.

“Daglo seems to want restructuring of the top army command to take place first, so that he can be part of it before the integration.”

In December, Burhan and Daglo signed a tentative deal with multiple factions — including the key civilian bloc, the Forces for Freedom and Change — as part of a two-phase political process toward a civilian-led transition.

But critics called the deal “vague” and cast doubt on the generals’ pledge to exit politics after a civilian government was installed.

“The December deal highlighted the disagreements which have their different aspirations at its core,” said Ismail.

Gizouli says the accord was “a delaying tactic” for Burhan, while Daglo sought “to improve his competitiveness” and bill himself as “an ally to the FFC.”

He said: “It is clear that neither of them has any intention to exit politics, as they have been investing in alliances that would allow them to continue.”

Daglo has been jet-setting across the region drumming up support, traveling to neighboring Eritrea and Equatorial Guinea, two African nations with close ties with Russia.

The day after Burhan visited Chad last month, Daglo started a visit of his own.

Analyst Kholood Khair said a recent initiative by Egypt has appeared to favor Burhan and “catalyzed renewed tensions between the generals.”

In February, Cairo hosted a workshop among multiple Sudanese factions including those who opposed the December deal, notably two ex-rebel commanders — Finance Minister Gibril Ibrahim and Darfur governor Minni Minnawi.

Khair, in an article for the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, said the Cairo initiative left political groups seeking to make pacts “with one general over the other.

“This is a false choice, and one that can only lead to further polarization of the political space and, potentially, an armed confrontation between Burhan and Hemeti’s forces, with disastrous consequences.”

Daglo, in a recent speech to RSF troops, said his disagreement was not with the armed forces.

“The disagreement is with the people clinging on to power,” said Daglo, insisting he backed the installation of a civilian government.

“We are against anyone who wants to be a dictator.”

On Saturday, Sudan’s armed forces hit back, dismissing accusations of “the unwillingness” of the army’s generals “to complete the process of change and democratic transformation.”

It said in a statement: “It is an open attempt to gain political sympathy, and to obstruct the transitional process.”

On Sunday, Sudan’s ruling sovereign council said Burhan and Daglo held security talks.

Ismail said that while the outright military confrontation that many fear is unlikely, it is not the only potential outcome. “It’s a political disagreement ... but it could push the Sudanese people to rise up and turn on all of them,” Ismail said.