DUBAI: Fresh findings by archeologists suggest the existence of a possible bishop’s palace — potentially Omani — near a recently discovered Christian monastery on the UAE’s Siniyah Island, off the coast of the state of Umm Al-Quwain.

A series of walls and rooms were uncovered last year that intrigued archeologists and historians involved in the excavation process on Siniyah Island, according to Tim Power, an archeology professor at UAE University.

“This year, we came back to expand the trenches to try to understand what’s going on there,” said Power. (AN Photo/Maria Botros)

“It seems that we really have an interesting building that might be interpreted as an abbot’s house or perhaps even a bishop’s palace,” he continued.

The archeology professor explained that similar buildings had been found in the Arabian Gulf over the years, which has helped historians and archeologists create parallels.

Power added that recently what is thought to be a bishop’s palace was uncovered in Bahrain that had similar characteristics to the structure discovered on Siniyah Island.

The newly discovered structure on Siniyah Island believed to be a bishop's palace. (AN Photo/Maria Botros)

“Historical sources, in particular the acts of the synods of the Nestorian church, mention a bishop of Oman between the fifth and seventh centuries,” said Power.

Oman during that period included the region that later became the northern emirates of the UAE, so it is possible this was the actual palace of a bishop, he added.

This year, the focus has shifted to excavating a different part of the island, with extensive work carried out on settlements and other structures surrounding the monastery.

Findings on the island suggest the presence of both Christian and Muslim communities, who are believed to have coexisted during a period of time.

They also shed light on the transition from late antiquity to early Islam, just before the Arab conquest.

Power, who was invited by the Tourism and Archeology Department of Umm Al-Quwain to put together a “dream team of leading experts,” chose individuals who can contribute to the project.

“The goal of this season will be to outline the context of the monastery so it’s not just an isolated structure in the middle of this sand pit,” said Michele Degli Esposti, a researcher at the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

(AN Photo/Maria Botros)

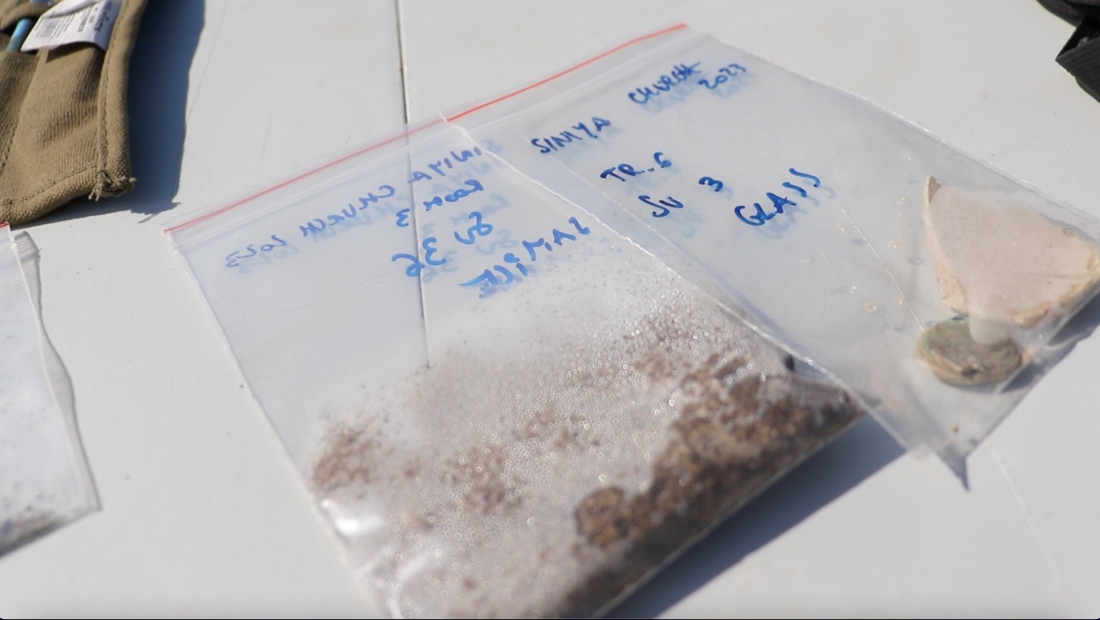

Esposti, who sat categorizing artifacts and materials found during the dig, explained why the site of the alleged bishop’s palace was different than other structures.

“This area, contrary to what happens in the settlement, is quite poor in material remains,” he said.

“One reason is that the core complex, which had a very nice plaster floor, was constantly kept swept and clean, so we found very little materials left behind.”

A possible warehouse was found in the vicinity of the structure thought to be the bishop’s palace, containing further clues for archeologists to draw conclusions.

“The bulk of the materials are made of pottery, quite remarkable quantities of glass as seen in the settlements, and a few stone vessels, which are quite interesting,” said Esposti. (AN Photo/Maria Botros)

Radiocarbon dating used to assess the pottery excavated suggests that the community believed to have occupied the island was there between the seventh and eighth centuries.

Esposti said similar methodologies will be used to determine the age of the objects recently found to further narrow down the window of the predicted time period.

Findings will allow archeologists and researchers to better understand the pattern of occupation in the new site discovered on the island in order to draw relevant conclusions. (AN Photo/Maria Botros)

The excavation process, which has a more multidisciplinary approach, involves experts and materials from around the world to aid archeologists on site.

It is also the first time that TAD UAQ is hosting students from the New York University of Abu Dhabi to participate in the excavation process.

Hoor Al-Mazrouei, an Emirati biology student at NYUAD, participated in the excavations taking place in the settlements where she helped find a pot potentially used for cooking.

“While we were digging, we found that it doesn’t have a base, and that’s probably why it’s not used for storage but used for baking bread or used as a cooking base,” said Al-Mazrouei. (AN Photo/Maria Botros)

NYUAD students were involved in the process from Jan. 4-20, alongside archeologists from TAD UAQ such as Ammar Al-Banna.

Al-Banna, who predicts that the island will welcome visitors in the foreseeable future, said the first step is to uncover all findings to proceed.

“By uncovering them, we hope to understand why they are here and what the relationship between all the structures and the sites next to them is,” he said. “Of course, with the finds, some will be studied, some will be exhibited.”

Excavation work on the island will continue until March and will end before the Ramadan fast begins.

Siniyah Island’s monastery is the second to be found in the UAE, with the first discovered in Abu Dhabi’s Sir Bani Yas Island in the 1990s.