ALEPPO, Syria: At 2:30 a.m. on January 22, Sheikh Maksoud, a Kurdish-majority neighborhood in Syria’s Aleppo, was struck by tragedy. A five-story residential building collapsed, burying dozens of residents under a mountain of rubble.

After round-the-clock rescue efforts, 16 bodies were recovered and two survivors were brought to the neighborhood’s hospital for treatment. According to state media, the structure’s foundations had been weakened by water leakage.

For residents of Sheikh Maksoud, this is just the latest in a litany of disasters as the neighborhood struggles to survive under a crushing siege imposed by opposition and regime groups alike.

Over the past decade, Aleppo has been transformed from a once-thriving trade, travel and cultural hub into a battleground, leaving much of the city in ruins.

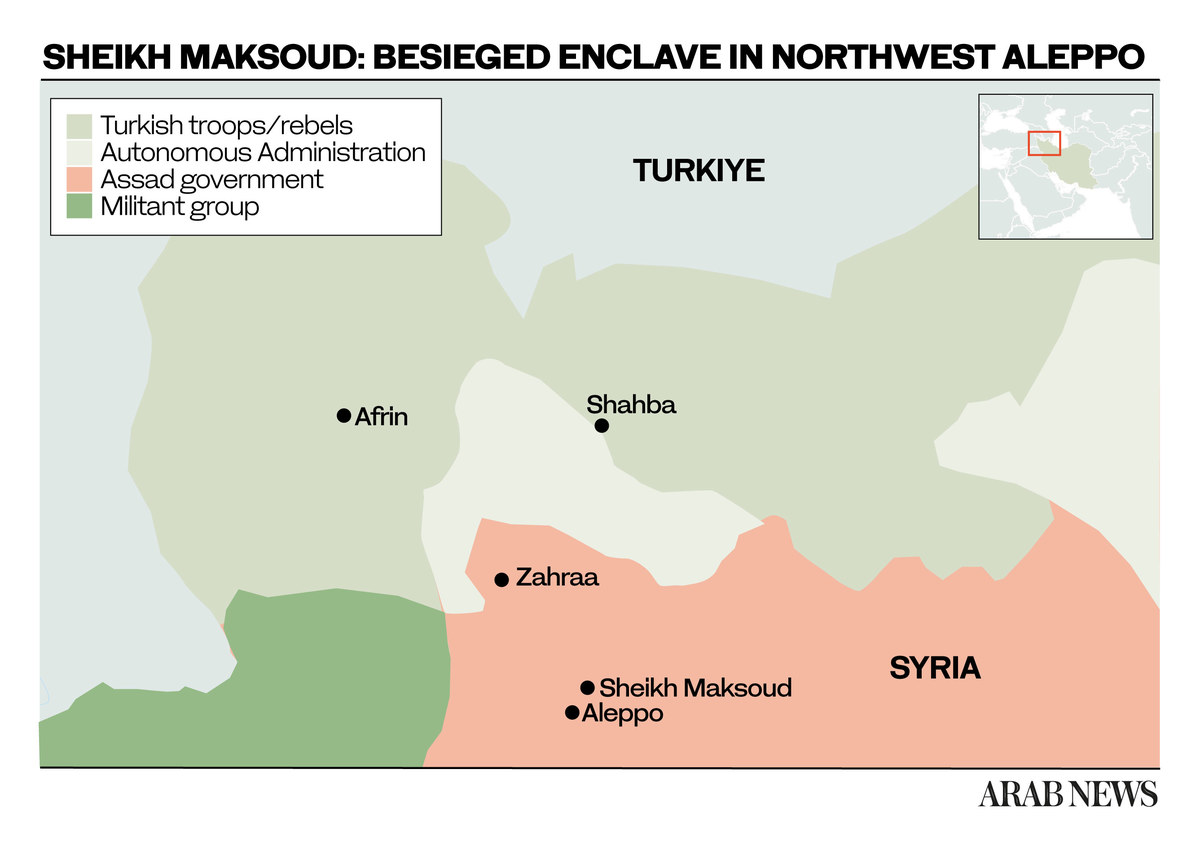

Slowly, as the frontline moved elsewhere, Syria’s second-biggest city began to rebuild. However, Sheikh Maksoud, an autonomous enclave on the northwestern edge of the city, continues to fight for its life.

A family of internally displaced persons cooks a meal in Serdem Camp in Shahba, located between Afrin and Aleppo. AN Photo by Ali Ali

With half of the 2-square-kilometer neighborhood left destroyed after years of fighting between opposition groups and the neighborhood’s self-defense militias, the people of Sheikh Maksoud have done their best to continue living life as normal.

Over the past year, one force has been particularly brutal in depriving the neighborhood’s residents of everything from medicine to fuel and even food — the regime’s Iran-backed Fourth Division.

With winter biting, residents are struggling to cope.

“We’ve been burning trash because there is no fuel. It gave me a chest infection. I’ve been to the hospital twice this week,” said one resident of Sheikh Maksoud when Arab News visited the neighborhood in December.

Merai Sibli, a member of the General Council of Sheikh Maksoud and Ashrafiyah, said fuel had not reached the neighborhood for more than 50 days, with residents often receiving an hour or less of electricity per day as their private generators run empty.

“We can’t get fuel. Children and the elderly can’t cope with the cold,” said Sibli. “They don’t even allow medicine to pass here. What is allowed to pass is very expensive. Six months ago, they cut off our flour, and all bakeries were closed for nearly 20 days.”

According to Sibli, the Fourth Division demands up to SYP2.5 million (more than $380) for every fuel truck which enters the neighborhood — a heavy price, considering the average monthly salary in Syria is just SYP150,000 (approximately $23).

“Soon our workshops and tailors will shut down because they are without electricity, and in the end, all of our youth will be out of work and forced to sit at home in the dark.”

The Fourth Division has roots going back to the 1980s, when Hafez Assad’s brother Rifaat fled the country and his paramilitary group, Defense Companies, dissolved into several militia groups.

The Fourth Division would eventually form out of these groups, and was later used to crush uprisings in Deraa, Baniyas, Idlib and Homs from the outset of the Syrian crisis. A Human Rights Watch Report from 2011 documents the Fourth Division’s participation in several abuses, including arbitrary detentions and the killing of protesters.

The de facto commander of the division is Maher Assad, the younger brother of Syria’s President Bashar Assad. According to an investigation by the Lebanese Al-Modon newspaper, the Fourth Division has been enjoying Iranian support — material, financial and advisory — since the start of Iran’s intervention in the Syrian civil war.

FASTFACTS

• Sheikh Maksoud is under the control of the US-backed Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces.

• Many buildings in Aleppo were destroyed or damaged during Syria’s 11-year conflict.

• Aleppo is Syria’s second largest city and was its commercial center before its destruction.

Early on in the conflict, the Syrian military was overwhelmed by defections and internal conflict, an effect from which the Fourth Division was not spared. As with many other units in the Syrian army, the Fourth Division was forced to rely on Iranian militias to bolster its strength.

The Fourth Division’s siege is not limited to Sheikh Maksoud. It extends to the city’s northern countryside, in the Shahba region, between Afrin and Aleppo. Shahba includes the town of Tel Rifaat (with a population of approximately 18,500, of which 15,700 are internally displaced persons, or IDPs) and five camps, which are all home to thousands of IDPs from the Afrin region.

At some regime checkpoints in Shahba, photos of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei are displayed next to photos of Bashar and Hafez Assad.

“No one is joining the Syrian military anymore. Their soldiers are all Iranian mercenaries. When those mercenaries come here, their aim is to take everything and share it with the state,” Muhammad Hanan, the co-chair of the Tel Rifaat district, told Arab News.

Hanan explained that the Iranian militia presence in the Shahba region serves mainly to protect the Shiite majority towns of Nubl and Zahraa, between Tel Rifaat and Aleppo.

From 2013 to 2016, the region was controlled by opposition groups, which were ousted by the Kurdish-led People’s Protection Units, or YPG. At that time, Syrian state military presence was mainly limited to small towns and villages in the area.

The Iran-backed Fourth Division’s siege is not limited to Sheikh Maksoud but extends to the Shahba area. AN Photo by Ali Ali

However, after the Turkish invasion of Afrin in 2018, government forces — and consequently, Iranian mercenaries — began to grow in number on the pretext of protecting the region from Turkish-backed opposition groups.

“In the end, they are not defending anything. Until now, the Syrian state takes every opportunity to weaken us and take over all of Shahba,” Hanan said.

Hanan and other local officials told Arab News that regime checkpoints block vital aid from the UN and other NGOs from reaching the region.

“The regime’s Fourth Division has closed the roads. If you want to bring something from outside, like fuel or propane, you have to give them a cut,” Dr. Azad Resho, administrator of Avrin Hospital in Shahba, told Arab News.

“It’s the same with the medicine. It has to come from the regime side. When international health organizations give aid to Syria, because the Syrian regime has status, all aid has to come through the regime.

“There are also international forces here, like Russia and Iran. It is all a political game. Even if the regime were to give aid, it must be in the interests of these forces. Because of this, we have become the victims of politics.”

Hassan, an administrator in the Shahba branch of the Kurdish Red Crescent, told Arab News: “The situation is terrible. There is no medicine at all. We just deal with emergency cases. We have no dermatologists, no nephrologists, and we have no equipment such as MRI machines.

“For patients with these needs, we have to send them to Aleppo. That has its own problems; the regime often prevents these people from entering (the city).”

A file photo from January 2017 shows Syrians walking past a poster of President Bashar Assad in Aleppo’s Saadallah Al-Jabiri Square. AFP

Under the suffocating embargo of Sheikh Maksoud and the Shahba region, however, there is one commodity that the Fourth Division appears happy to allow into these areas — drugs.

Last year, a New York Times investigation discovered that the Fourth Division was responsible for the production and distribution of Captagon pills and crystal meth across Syria, with the division moving the drugs to border crossings and port cities.

“Just recently, we confiscated and burned 124 kg of hashish. These 124 kg were brought in by the Syrian regime — by the Fourth Division, Hezbollah and other Iran-backed groups. They attempted to bring it in containers of oil,” Qehreman, an official in the Internal Security Forces of Sheikh Maksoud, told Arab News.

“They want to bring some things in, especially narcotic pills, with their members, and spread them among the people.”

Sibli said that despite the siege, “our people are very resilient.”

“Does the regime want us to lose and return us to the year 2007? They insist we must all be under one flag, one language and one leader.

“Because we in Sheikh Maksoud want coexistence and brotherhood of the peoples, the regime doesn’t accept us. But of course, people who have found their freedom will never return to the regime’s embrace.”