POISSY, France: From the market stall outside Paris that she’s run for 40 years, Yvette Robert can see first-hand how soaring prices are weighing on France’s presidential election and turning the first round of voting on Sunday into a nail-biter for incumbent President Emmanuel Macron.

Shoppers, increasingly worried about how to make ends meet, are buying ever-smaller quantities of Robert’s neatly stacked fruits and vegetables, she says. And some of her clients no longer come at all to the market for its baguettes, cheeses and other tasty offerings. Robert suspects that with fuel prices so high, some can no longer afford to take their vehicles to shop.

“People are scared — with everything that’s going up, with prices for fuel going up,” she said Friday as campaigning concluded for act one of the two-part French election drama, held against the backdrop of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Macron, a political centrist, for months looked like a shoo-in to become France’s first president in 20 years to win a second term. But that scenario blurred in the campaign’s closing stages. The pain of inflation and of pump, food and energy prices that are hitting low-income households particularly hard subsequently roared back as dominant election themes. They could drive many voters Sunday into the arms of far-right leader Marine Le Pen, Macron’s political nemesis.

Macron, now 44, trounced Le Pen by a landslide to become France’s youngest president in 2017. The win for the former banker who, unlike Le Pen, is a fervent proponent of European collaboration was seen as a victory against populist, nationalist politics, coming in the wake of Donald Trump’s election to the White House and Britain’s vote to leave the European Union, both in 2016.

In courting voters, Macron has economic successes to point to: The French economy is rebounding faster than expected from the battering of COVID-19, with a 2021 growth rate of 7 percent, the highest since 1969. Unemployment is down to levels not seen since the 2008 financial crisis. When Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, sparking Europe’s worst security crisis since World War II, Macron also got a polling bump, with people rallying around the wartime leader.

But the 53-year-old Le Pen is a now a more polished, formidable and savvy political foe as she makes her third attempt to become France’s first woman president. And she has campaigned particularly hard and for months on cost of living concerns, capitalizing on the issue that pollsters say is foremost on voters’ minds.

Le Pen also pulled off two remarkable feats. Despite her plans to sharply curtail immigration and dial back some rights for Muslims in France, she nevertheless appears to have convinced growing numbers of voters that she is no longer the dangerous, racist nationalist extremist that critics, including Macron, accuse her of being.

She’s done that partly by diluting some of her rhetoric and fieriness. She also had outside help: A presidential run by Eric Zemmour, an even more extreme far-right rabble-rouser with repeated convictions for hate speech, has had the knock-on benefit for Le Pen of making her look almost mainstream by comparison.

Secondly, and also stunning: Le Pen has adroitly sidestepped any significant blowback for her previous perceived closeness with Russian President Vladimir Putin. She went to the Kremlin to meet him during her last presidential campaign in 2017. But in the wake of the war in Ukraine, that potential embarrassment doesn’t appear to have turned Le Pen’s supporters against her. She has called the invasion “absolutely indefensible” and said Putin’s behavior cannot be excused “in any way.”

At her market stall, Robert says she plans to vote Macron, partly because of the billions of euros (dollars) that his government doled out at the the height of the COVID-19 pandemic to keep people, businesses and France’s economy afloat. When food markets closed, Robert got 1,500 euros ($1,600) a month to tide her over.

“He didn’t leave anyone by the side of the road,” she says of Macron.

But she thinks that this time, Le Pen is in with a chance, too.

“She has changed the way she speaks,” Robert said. “She has learned to moderate herself.”

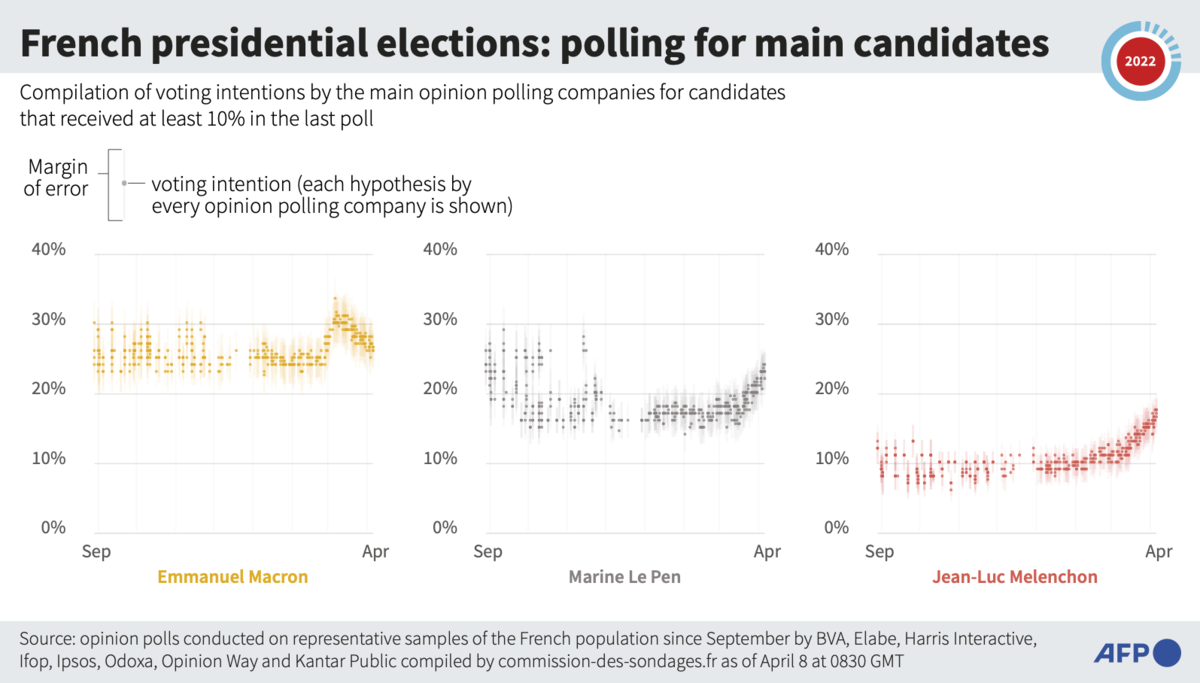

Barring a monumental surprise, both Macron and Le Pen are expected to advance again from the first-round field of 12 candidates, to set up a winner-takes-all rematch in the second-round vote on April 24. Polls suggest that far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon is likely to finish out of the running in third place. Some of France’s overseas territories in the Pacific, the Caribbean and South America vote Saturday, before Sunday voting on the French mainland.

When Macron made a campaign stop in Poissy, the town west of Paris where Robert has her stall, in early March, pollsters had him leading Le Pen by double digits. Although a Le Pen victory still appears improbable, much of Macron’s advantage has subsequently evaporated. Kept busy by the war in Ukraine, Macron may be paying a price for his somewhat subdued campaign, which made him look aloof to some voters.

Market-goer Marie-Helene Hirel, a 64-year-old retired tax collector, voted Macron in 2017 but said she’s too angry with him to do so again. Struggling on her pension with rising prices, Hirel said she is thinking of switching her vote to Le Pen, who has promised fuel and energy tax cuts that Macron says would be ruinous.

Although Le Pen’s “relations with Putin worry me,” Hirel said that voting for her would be a way of protesting against Macron and what she perceives as his failure to better protect people from the sting of inflation.

“Now I’m also part of the ‘all against Macron camp,” she said. “He is making fools of us all.”