ALULA: Once known as a lost city of the dead, AlUla is today a living museum that is home to ancient civilizations, historical sites and archaeological wonders dating back 200,000 years.

Located northwest of Saudi Arabia and covering an area of more than 22,000 sq. km, it is known for its sandstone mountains and fertile oases harboring plentiful resources. Due to its location as an ancient crossroads on the Arabian Peninsula, it was an ideal resting place for caravan traders who would travel great distances in the region.

The AlUla valley is a landscape of striking contrasts, featuring strange rock formations carved by man and nature, petroglyphs and engravings, and a lush oasis that has thrived since ancient times.

The AlUla valley is a landscape of striking contrasts. (AN photo)

AlUla was the capital of the kingdoms of the Arab Dadan and Lihyan civilizations, which prospered in the desert oasis from 600-300 B.C. by controlling the incense trade routes that passed through the valley.

Engravings of hunters holding spears on horses and camels can be seen on AlUla’s mountains, which held religious significance to the Dadanites and Lihyanites who, according to local tour guide Abdulkarim Al-Hajri, worshipped whatever benefited them.

“In the past, Arabs only worshipped the divine trinity: The star, the sun and the moon,” he said. “For the Arabs, the camel had a communal significance, so did the bull, which represented fertility, and the lion, which represented strength and resilience.

“Man started with symbols, then drawing, then writing, all of which can be found on these mountains,” Al-Hajri said. “Some people say these are the different Arabic languages and that is wrong; in fact, they are different Arabic writings — Arabic is the mother language, one language that evolved through time.

“The current Arabic style of writing is derived directly from the Nabataean writing,” he added.

The AlUla valley is a landscape of striking contrasts. (AN photo)

Visitors to the area can inspect the markings, and Lihyani and Thamudi inscriptions with the help of the local guides, who told Arab News that many of AlUla’s treasures have yet to be discovered.

The Nabatean kingdom followed, whose people lived and thrived in the city of Hegra for over 200 years until it was conquered by the Roman Empire in A.D. 106. The Nabataeans were one of several nomadic Bedouin tribes that roamed the Arabian Desert. They most likely originated from west of the Arabian Peninsula, in Hejaz, due to similarities in the spoken Semitic languages and deities worshipped in both areas.

Hegra, a 52,000-square-meter ancient city, was the kingdom’s principal southern city and today features more than 100 well-preserved tombs, with the biggest being Qasr Al-Farid or “The Lonely Castle.” It is one of the most recognized and frequented sites in AlUla. Hegra is also the Kingdom’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The AlUla valley is a landscape of striking contrasts. (AN photo)

The Nabateans were skilled at harnessing natural water resources, so much so that travelers sought their help when passing by the arid lands.

At Hegra, they tapped into underground reserves of water and devised systems of channels for directing and storing it. The name Nabataean has been linked to the Arabic word “Nabatu,” meaning water that springs from the well.

The tombs at Hegra were built to hold the remains of families or groups, whose status was reflected in the size or decoration of their final resting places. Higher up the mountains were simpler pit graves where people of lower social status were buried.

One deity worshipped by the Nabateans was Dushara, an eagle that guarded the entrance to several tombs in Hegra. The bird is now headless, with one theory suggesting the Romans decapitated it as a way of claiming the land and ensuring the Nabateans’ god perished with them.

The French orientalist Charles Auguste Huber, who came to AlUla when he was commissioned by his country to explore the Arabian Peninsula between 1878 and 1884. (Supplied)

Across the Hegra tombs between two jagged sandstone mountains sits Al-Diwan (the court). Carved into the hillside to shield it from the wind, it is a grand square chamber containing three stone benches that served as a meeting room for the Nabataean rulers, who would convene to discuss the affairs of the city and its people. It is one of the few examples of non-funerary architecture in the city.

Following the framework of Saudi Vision 2030, the Journey Through Time Masterplan was launched in April, which Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who is chairman of the Royal Commission for AlUla, described as “a leap forward to sustainably and responsibly develop AlUla, and share our cultural legacy with the world.”

The Sharaan Nature Reserve, one of the strategic projects carried out by the commission, extends over an area of 1,500 sq. km, with varied terrain, mountains and valleys covered with wild flowers and desert areas, embracing a variety of wild animals.

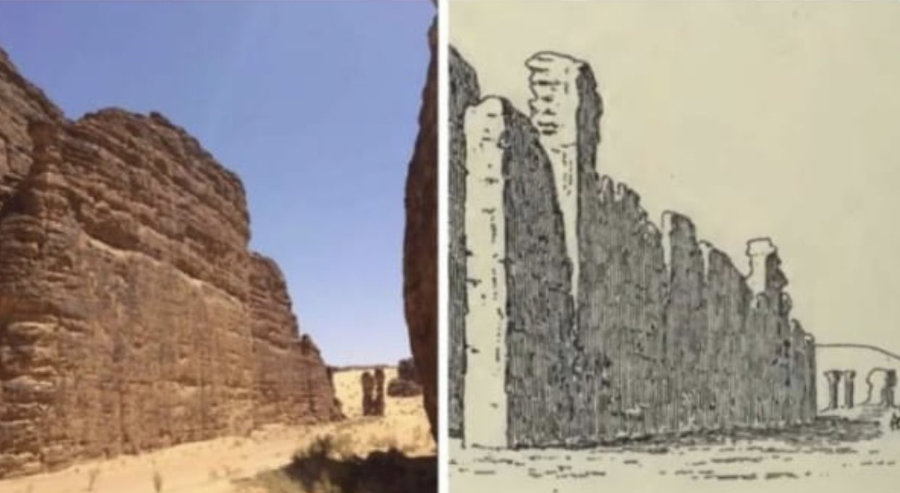

Charles Auguste Huber drawing of the southern facade of Rawdat Al-Naga, found in the Sharaan reserve circa 1878-1884. (Supplied)

The French orientalist Charles Auguste Huber drew the southern facade of Rawdat Al-Naga, in the Sharaan reserve, between 1878 and 1884 when he was commissioned by France to explore the Arabian Peninsula.

When passing through the Rakab Mountains, he said: “We passed through mountains, and were they in Europe would have become overcrowded with tourists.”

When passing through the Rakab Mountains, Huber said: “We passed, fated, through mountains, and were they in Europe would have become overcrowded with tourists.” (Supplied)

One of AlUla’s most prominent landmarks is the Tantora sundial, which can be found in the old town. The Winter at Tantora festival started last week to coincide with the traditional planting season in AlUla, known as Al-Marba’aniya.

The six-week festival is named after the sundial because of the essential role it played in people’s lives and the annual event is a key date on the calendar. It is also part of the three-month AlUla Moments, which is back for its third edition and allows visitors to experience a range of activities and engage in cultural exploration.

Tickets can be booked via the official website, Experiencealula.com.