ABU DHABI, UAE / BOGOTA, Colombia: The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted societies the world over, exposing not only the vulnerabilities of national economies, supply chains and health infrastructure, but also the deep social inequities within and among nations.

Experts had long warned the world was woefully underprepared for a pandemic, lacking the necessary preparedness, surveillance, alert systems, early response infrastructure and leadership to prevent a global outbreak.

“The world was not prepared,” Michel Kazatchkine, former executive director of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, said at the World Policy Conference (WPC) in Abu Dhabi on Saturday.

“All the public health officials, experts, previous international commissions and review committees had warned of the potential of a new pandemic and urged for robust preparations since the first outbreak of SARS.

Relatives carry the body of a person killed by COVID-19 amid burning pyres of other victims at a cremation ground in New Delhi on April 26, 2021. (AFP file photo)

Instead, governments have spent the past year and a half playing catch-up, squabbling over limited supplies of medical and protective equipment, implementing inconsistent containment measures, and jealously guarding their health data.

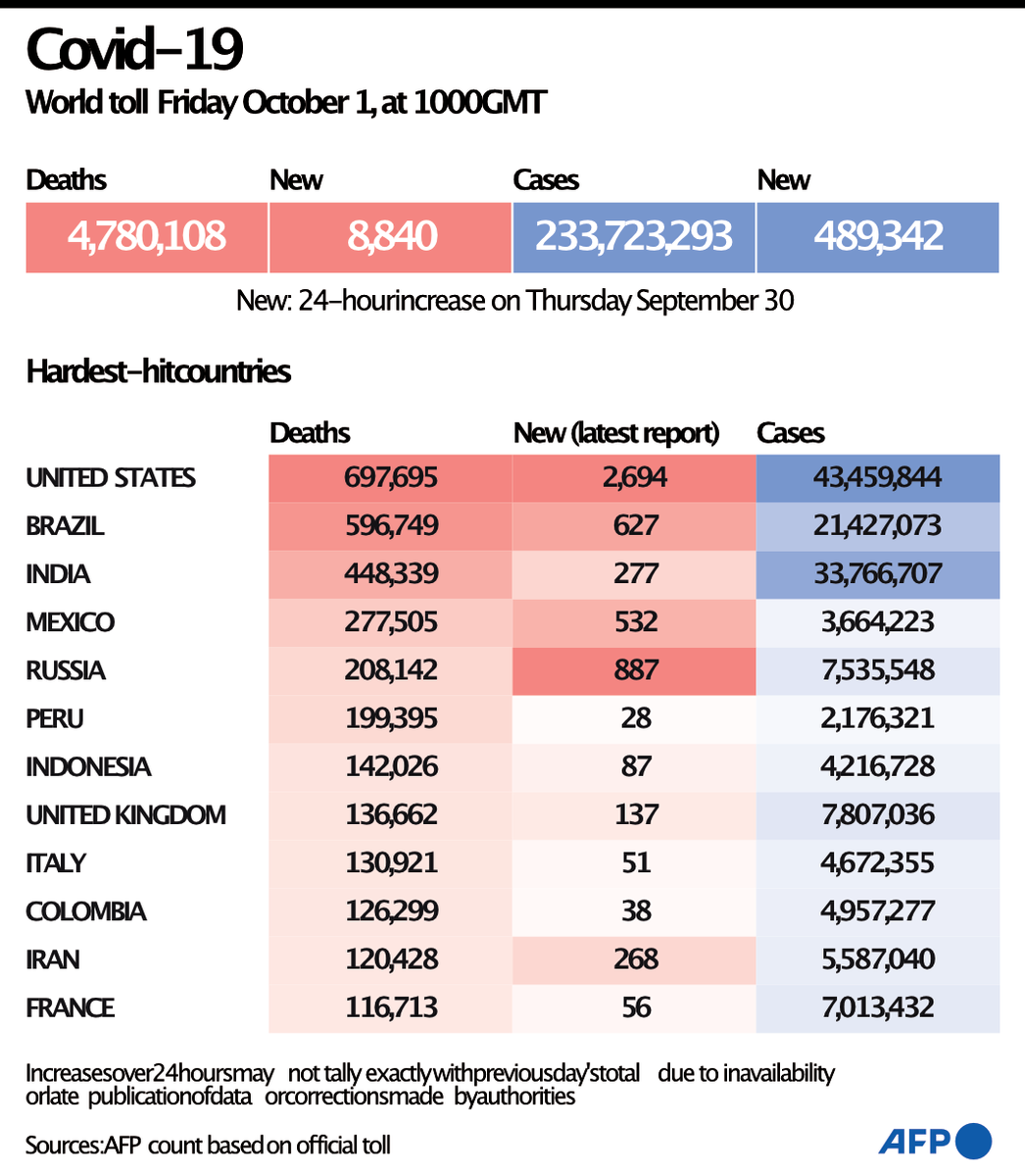

During that time, more than 235 million cases of the novel coronavirus have been reported worldwide and nearly 5 million people have died. At its peak in 2020, half of the world was in lockdown and 90 percent of children were missing out on their education.

Economists estimate that the pandemic will have cost the world economy roughly $10 trillion in output by the end of 2021 — just a fraction of which could have been spent on containing or preventing the pandemic from happening in the first place.

“COVID-19 took large parts of the world by surprise,” Kazatchkine said. “National pandemic preparedness has been vastly underfunded despite the clear evidence that the cost is a fraction of the cost of responses and losses incurred when a pandemic actually occurs.”

In May this year, the Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness and Response identified weak links at every link in the chain. It found that preparation was inconsistent and underfunded, while the alert system “was too slow and too meek.”

It said that governments failed to deliver a rapid or coordinated response when the World Health Organization declared that the outbreak constituted a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on Jan. 30, 2020. Indeed, most only responded when infections began to rise.

INNUMBERS

4.81 million: Worldwide COVID-19 deaths as of Oct. 3, 2021.

$4 trillion: Global GDP loss (2020 & 2021) due to COVID-19 (UNCTAD).

$2.4 trillion: Tourism sector’s loss in 2020 alone (UNCTAD).

The IPPR report also concluded that the WHO had not been granted sufficient powers to respond to the crisis — a disaster that was further exacerbated by a distinct lack of political leadership.

To explore whether governments could have handled the pandemic better and what lessons might be drawn to help prevent future outbreaks, Kazatchkine chaired a WPC panel discussion titled “Health as a Global Governance Issue: Lessons from COVID-19 Pandemic.”

During the session, the panelists laid out four key recommendations for governments and multilateral organizations to take on board to ensure future pandemics are better handled or stopped in their tracks. Their conclusions will be discussed at a special session of the World Health Assembly in November.

An expert panel at the World Policy Conference in Abu Dhabi has provided four key recommendations to boost global health equality and preparedness as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to claim lives. AFP

Their first recommendation concerned the establishment of a new financing mechanism to invest in preparedness and inject funds immediately at the onset of a potential pandemic. This would help to prevent a repeat of the widespread dithering seen among governments in late 2019 and early 2020.

Their second recommendation called for a standing, pre-negotiated, multilateral platform to produce vaccines, medical diagnostic tools and supplies for rapid and equitable delivery as essential common global goods.

This would help address the shocking inequalities seen in the world’s supply chains, whereby whole regions suffered extreme shortages of cleaning chemicals, personal protection equipment and medical oxygen for hospitals, and has led to a situation where many rich countries are approaching full vaccination while several of the poorest have inoculated barely 5 percent of their populations.

A traditional chief in Ivory Coast receives a vaccine against COVID-19 at a mobile vaccination center in Abidjan on Sept.23, 2021. (REUTERS/File Photo)

“When the COVID-19 pandemic began, two things became very obvious to those of us on the African continent,” Juliette Tuakli, CEO of CHILDAccra Medical and chair of the board of trustees at United Way Worldwide, told the WPS panel.

“One was that the West had huge capacity but little strategy, and we in Africa had a lot of strategy and little capacity. The second thing that was obvious was the importance of health as a national strategic asset within our economies.

“The pandemic highlighted health inequities that are ongoing, (plus) weaknesses in our systems such as (shortages). As well as the weak regional and domestic financing systems for procuring appropriate medications and vaccines, (not to speak of the prevalence) of very insidious health regulatory policies throughout the continent.

“Looking at the global stage, it’s important that we not just partner with other groups and agencies but that we have equal status within those relationships. There has to be some equity in our partnerships, here on, in terms of health and health governance, for us to be part of the solution, not just part of the problem.”

A woman prepares to receive a dose of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine at a school in Pattani, Thailand, on August 10, 2021. (AFP photo)

The WPC panel’s third recommendation called for strengthening and empowering the WHO to oversee and even grade nations on their preparedness for future outbreaks, to have greater control over vaccination campaigns, and to assume more overall leadership.

“Too many governments lacked solid preparedness plans, core public health capacities, organized multi-sectoral coordination and clear commitment from leadership. And this is not a matter of wealth,” Kazatchkine said.

“I believe that COVID-19 has shaken some of our standard assumptions that a country’s wealth will secure its health. Actually, leadership and competence may have counted for more than cash when it comes to responding to COVID-19.”

Finally, the experts recommended the establishment of global health-threat councils at the level of heads of state and government to ensure both political commitment and accountability in fighting and preventing pandemics, elevating such threats to the level of terrorism, climate change and nuclear proliferation.

Governments should look at health strategically, invest in the right equipment, have the right drugs, and secure their supply chain, says WPC forum panelist Jean Kramarz. (AFP file photo)

“It should be treated like a military topic — to invest in health well in advance to face a crisis,” said Jean Kramarz, director of healthcare activities at AXA Partners Group.

“If health is strategic, it means that governments should overinvest in health to make sure that they have the right equipment, they have the right drugs, they have secured their supply chain, and it should be done permanently. It should be a topic of national interest.”

While experts in health and good governance ponder the lessons of the pandemic with a view to improving readiness for the next major outbreak, medical professionals are still fighting the crisis at hand. An array of aggressive virus variants, overstretched ICU facilities and sluggish vaccination campaigns are keeping the rate of infection stubbornly high.

“The pandemic is not yet over,” Kazatchkine said. “As we speak, over 400,000 new cases and 10,000 deaths are reported globally every day. Current hotspots are the US, Brazil, India, followed by the UK, Turkey, the Philippines and Russia.

“National responses across the world span from the complete lifting of restrictions in Denmark to new statewide lockdowns in Australia and a growing political and public-health crisis in the US.

“Where the number of infections increases, we see again unsustainable pressure on the health care system and on health care workers. So, the bottom line here is that the pandemic remains a global emergency and the future remains uncertain.”