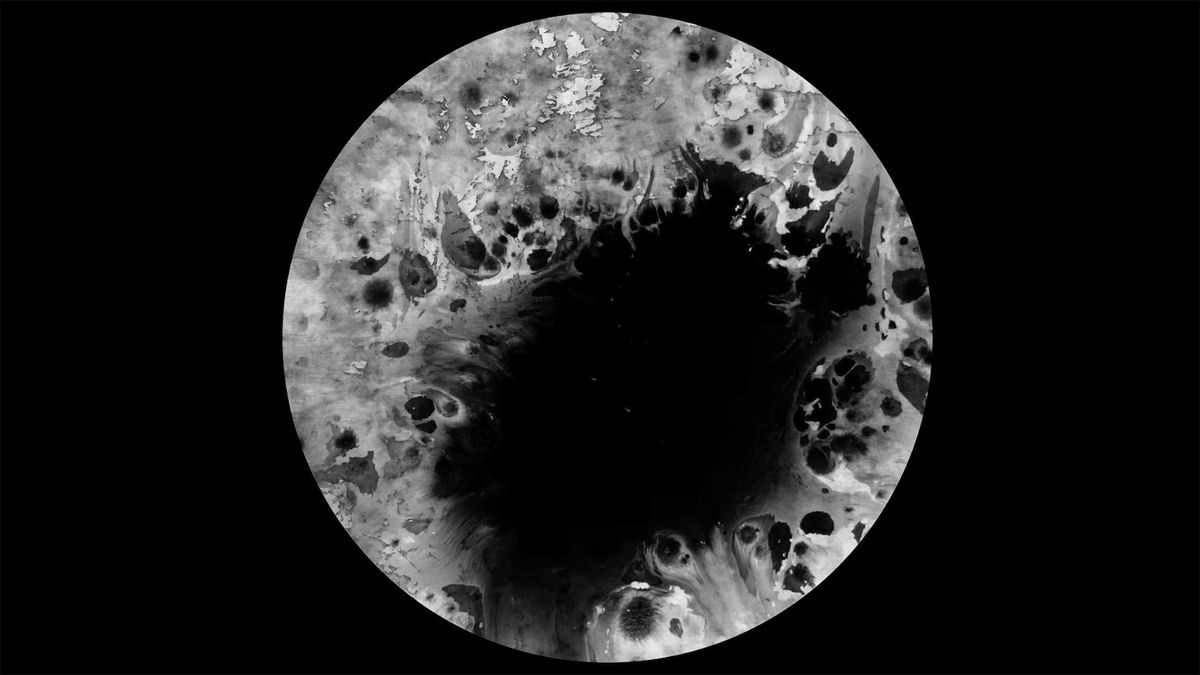

DUBAI: A large planet-like circular form dappled with what appear to be craters and a few black dots changes constantly in front of the viewer’s eyes.

This is “The Fifth Sun,” a textile mural projection with sound created in 2017 by Saudi artist Mohannad Shono. According to the artist, it explores self-fulfilling prophecies — and “self-inflicted wounds” — regarding destruction and rebirth. It is one of the works that Shono — one of Saudi Arabia’s most promising contemporary artists — is showing at BIENALSUR (the International Biennial of Contemporary Art of the South) in Buenos Aires, through the Saudi Ministry of Culture.

The Riyadh-born artist’s trajectory is as inspiring as it is unconventional. He started creating his own comic books as a child — a sideline he kept up even when studying architecture in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. Eventually, he decided to dedicate himself to his art on a full-time basis, and proceeded to publish one of Saudi Arabia’s first comic books through a small independent publishing house.

The Riyadh-born artist’s trajectory is as inspiring as it is unconventional. (Supplied)

He left the Kingdom in 2004 to pursue a career in advertising in Dubai and Sydney, but kept working on his art on the side. When he returned to Riyadh in 2015, he found the country greatly changed and began participating in underground art exhibitions, establishing himself as a rising name in the local Saudi art movement.

His work has since been exhibited at home and abroad (including South Korea and Germany) and he has participated in artist residencies in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany.

At the crux of Shono’s conceptual art that he makes from a variety of media, including works on paper, film, and installation, is an inquiry into human understanding. His works — while not representative of the human form or the outside world — are loaded with suggestion and emotion. They are created, Shono says, from “an imagined state of being, one devoid of a particular time and place,” which, he says, ultimately frees him from his own sense of displacement, stemming from his upbringing as a Syrian in Saudi Arabia.

“Our Inheritance of Meaning,” 2019. (Supplied)

Shono is exhibiting five other works at BIENALSUR: “The Silent Press” (2019), “The Name of All Things” (2019), “The Reading Ring” (2019), “Our Inheritance of Meaning” (2019), and a new ink-on-paper work called “Stolen Words.”

The majority of these were also displayed in the artist’s solo exhibition “The Silence is Still Talking” at Jeddah’s Athr Gallery.

“These works were exploring our relationship with the nature of words and their meaning,” Shono says. “They take us through a journey of the hard work needed to reform the word. We begin by grinding down the ‘hardened word,’ by which I mean those things that we are trying to break apart and re-understand — or break apart until they lose their meaning — to (create) new words with new meanings and maybe open up solutions that are desperately needed.”

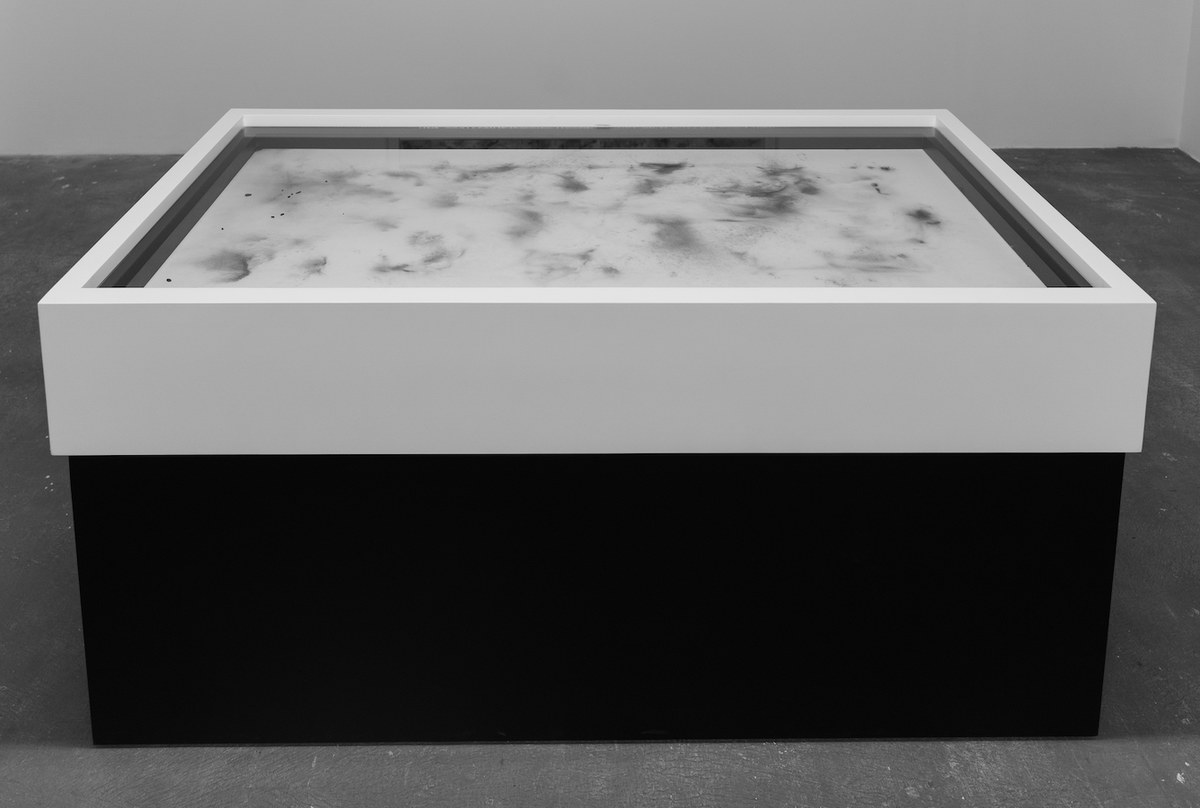

“The Name of All Things,” 2019. (Supplied)

“The Names of All Things” is a good example of what Shono is trying to achieve. It is an installation consisting of dust made from words written in charcoal that have been ground down. The dust lies on a vibrating table so that it is shaken across the canvas, the shapes it makes constantly being reformed into “limitless arrangements.”

“From the markings left behind from this process, new meanings to these old words are allowed to emerge,” explained Shono. “These are symbols that can potentially hold and embody new words and new meanings. While they are still illegible, they are in the process of being read.”

Much of Shono’s work explores the way in which storytelling influences contemporary society. “Human beings are hard-wired to gravitate towards constructed narratives,” he says. “We love to consume narrative in all of its different mediums — books, shows, movies, et cetera. This belief in narrative also helps us come together as tribes: We can gather around a narrative and that helps us organize ourselves according to certain rules (set out in) a story. It provides us with the power to organize in larger groups, gathered around a set of narratives and beliefs. Millions and millions of people can thus coordinate and be on the same page due to this commonly shared belief in a particular narrative — a narrative that everyone in this group has accepted as truth.”

“The Fifth Sun,” 2017. (Supplied)

The centerpiece of “The Silence is Still Talking” was “The Silent Press” — a large-scale installation composed of three attached pigment-on-paper scrolls that resemble an old printing press. The work is indicative of Shono’s explorations into the meaning behind the written word. “This is a printing press that is in a state of inactivity; it is thus silent and not in motion,” he says. “The pigments are agitated by sound so that one sees their resulting movements on paper, but without hearing the sound that made them appear so. I have taken intentionality out of my hands in an effort to discover new language and meaning.”

So instead of recognizable words, the scrolls are covered in undefined black forms, revealing a language all its own.

“I am interested in the power of fluid interpretations and readings,” Shono tells Arab News. “Inflexible meanings versus words that have an open, more fluid interpretation.”

“The Silent Press,” 2019. (Supplied)

Shono’s personal relationship with the written word is complicated. The artist is dyslexic and doesn’t feel comfortable writing in English or Arabic publicly, but these works allow him to “form my own language.” The ever-changing arrangements of that language naturally create ever-changing meanings for its ‘words.’

Shono reworked some of his pieces for BIENALSUR in light of his own, and other people’s, experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It often takes a few manifestations of a work to see the connection between things. They all speak to our relationship, personally and collectively, with change,” he says. “I feel like everything connects and resonates at the same time. It is all part of this continuous understanding of myself and my work and why I am doing what I am doing.

“And change keeps coming,” he continues. “My work is about how we can accept and appreciate change and accept a more fluid way of reading things — rather than a rigid interpretation of the text.”