ISLAMABAD: In many ways, the Doha agreement of February 2020 evoked memories of the US military’s humiliation in Vietnam half a century earlier.

The deal with the Taliban, which paved the way for the withdrawal of all foreign troops from Afghanistan, was no less ignominious for Washington. It was not a document of surrender but neither was it a declaration of victory for the most powerful military power on earth.

US officials had negotiated peace with the very insurgent leaders they once branded terrorists. In fact, several members of the Taliban negotiating team were former inmates of the notorious Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba.

Such is the irony of history: Yet another superpower began its drawdown just as the war-ravaged country observed the 32nd anniversary of the Soviet withdrawal. The Russians departed in 1989 after a decade in the Afghan mire. The Americans remained twice as long. The last US soldier is expected to leave in the next few weeks, before the symbolic date of Sept. 11.

Several of the Taliban negotiators in Doha had also fought the Soviets — with US support. At the time they were hailed by Washington as “holy warriors” who drove the Red Army out of Afghanistan with weapons supplied by the Americans.

Indeed, the irony was again apparent when Taliban fighters turned many of those same weapons on their former patrons.

US forces invaded Afghanistan in October 2001, following the 9/11 attacks, with little understanding of a land that has long been described as the “graveyard of empires.” It was an unwinnable conflict from the start but Washington fought tooth and nail to shape a narrative that would justify its continuance.

Quite how unprepared the Americans were was aptly summed up in 2015 by Lt. Gen. Douglas Lute, who said: “We were devoid of a fundamental understanding of Afghanistan — we didn’t know what we were doing. What are we trying to do here? We didn’t have the foggiest notion of what we were undertaking.”

Put in these terms, it is perhaps unsurprising that Afghanistan would become America’s longest war.

The Taliban’s resurgence was helped by a strategic miscalculation on the part of Washington, which decided to reempower Afghanistan’s former strongmen and warlords, causing old ethnic and tribal tensions to resurface. One of the biggest US mistakes was a failure to avoid the perception that the West was a party to the Afghan civil war.

Despite the deployment of tens of thousands of troops, the US could not defeat the insurgents once and for all. However, the Taliban’s revival as a powerful insurgent force should not have come as a surprise. In fact, the group was never really defeated.

Tens of thousands of Afghans were killed during the war, which cost close to $1 trillion. Since 2001, more than 775,000 US troops have been deployed to Afghanistan. The distorted statistics made it appear as though the US was winning the fight — but this was far from the truth.

US forces invaded Afghanistan in October 2001, following the 9/11 attacks. (AFP)

There were also fundamental disagreements within successive US administrations over precisely what America’s objectives were in Afghanistan. While some officials believed they were building a model democracy, others saw their role as reinventors of Afghan culture, including its views on women’s rights.

America’s attempts to curtail runaway corruption, build a competent Afghan army and police force, and put a dent in Afghanistan’s thriving opium trade did not work. Most of the US aid money was siphoned off by Afghan officials and warlords aligned with Washington, and the country devolved into a narco-state as a result of some seriously flawed policies.

Despite the billions of dollars spent on building and training the Afghan National Army and other branches of the security apparatus, local forces proved incapable of taking on the Taliban without American support.

Following the Doha agreement, it was left to the Taliban and the Afghan government to negotiate the future political setup of the country. It is certainly a tall order to expect the two warring sides to reach an arrangement that will satisfy all Afghan factions — a polarization that has only intensified over the past two decades of war and foreign occupation.

It was an unwinnable conflict from the start but Washington fought tooth and nail to shape a narrative that would justify its continuance. (AFP)

In addition the departure of the US forces has proven to be just as chaotic as their arrival. The hasty withdrawal has left a cavernous power vacuum.

The Taliban has leveraged the peace deal with the US to its advantage, while growing international recognition is giving the insurgents even greater confidence.

For many Afghans, however, the prospect of a return to Taliban rule is deeply disconcerting. Notwithstanding its solemn pledges, the Taliban has maintained a deliberate ambiguity about its political agenda, which is adding to the sense of confusion.

There were some indications that the ultraconservative Taliban might be willing to work within a pluralistic political system. Yet there was no clarity on whether the group would be willing to work within a democratic political and constitutional setup.

While the Taliban political leadership appears to be more moderate and flexible in its views, there is no evidence that the commanders in the field will be so amenable to change.

When the Taliban ruled Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001, it completely outlawed the right of women to education and work. The current leadership has offered assurances that it acknowledges the rights of women and will not oppose their education, but this has done little to quell the unease many people feel about potential Taliban action once foreign forces withdraw.

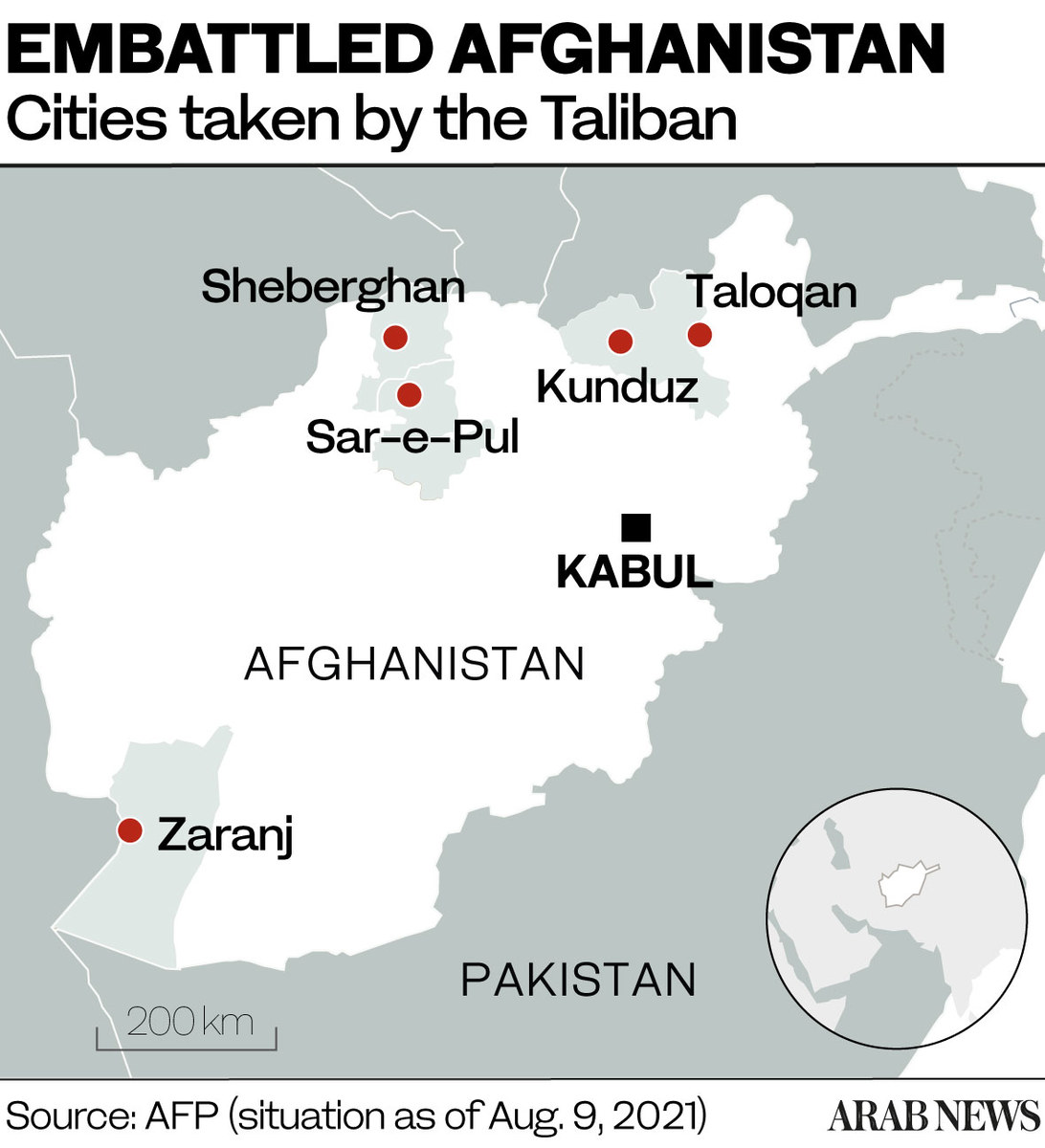

Decades of conflict have exacted a heavy toll on the lives of millions of Afghans and unleashed destruction that cannot be undone. The war has left the country as divided as ever. Through battlefield victories and expanding territorial control, the Taliban has gained the upper hand, creating a dangerous asymmetry of power. Many now fear the expansion of Taliban influence will lead to a resurgence of its tyrannical rule.

Regardless of who the adversary was at any given point in time, two generations of Afghans have known only war and it seems highly unlikely their misery will end any time soon.

Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand province. Once the winter residence of sultans from illustrious Islamic dynasties, the ruins of a thousand-year-old royal city in southern Afghanistan has become home to hundreds of people who have fled Taliban clashes. (AFP)

Inevitably, the withdrawal of American forces from the country will have a huge effect on regional geopolitics. Historically, the country’s strategic geography has made it vulnerable to interference from outside powers and proxy wars.

A full-scale civil war could lead Pakistan, India, Russia and Iran to back different factions and themselves become more deeply involved in the conflict. The spillover effects of spiraling instability and conflict in Afghanistan could prove disastrous.

Without a sustainable agreement among surrounding powers that guarantees Afghanistan’s security and its neutrality, the country might become the center of a costly proxy war, with various powers supporting rival factions across ethnic and sectarian lines.

Such an agreement is also critical to prevent Afghanistan reverting to a hub for global terrorism. A negotiated political settlement, intertwined with a regional approach, is the only desirable endgame.