DUBAI: Just when the international community thought it had one less conflict to contend with, concerns were reignited earlier this month as news broke of tribal clashes in Sudan’s Darfur region. By the time the dust had settled, at least 250 lives had been lost, hundreds of people had suffered injuries and more than 100,000 Sudanese had been displaced in two different states.

Perhaps inevitably, fingers are being pointed at Sudan’s joint-military-civilian government, which last month took responsibility for security in Darfur from the UN and the African Union, whose hybrid UNAMID mission peacekeepers had kept violence somewhat under check in the area for the last 13 years.

Experts think the announcement following a UN Security Council resolution on Dec. 22, 2020, that the UNAMID was ending its mission, indirectly contributed to the latest outbreak of violence. On Dec. 31, the force formally ended its operations and announced plans for a phased withdrawal of its approximately 8,000 armed and civilian personnel within six months.

The war had erupted when Darfur’s ethnic minority rebels rose up against dictator Omar Bashir’s Islamist government. (AFP/File)

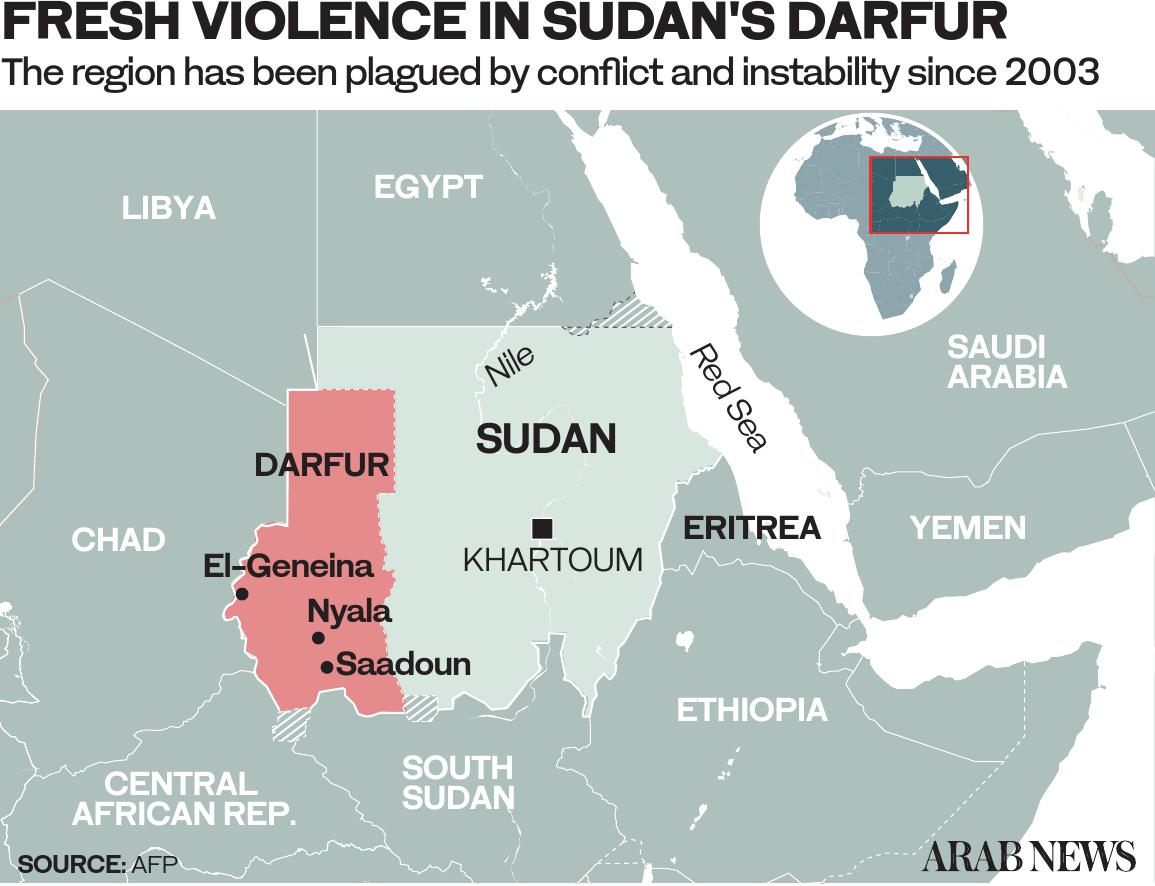

The violence in El-Geneina, the capital of West Darfur, began on Jan. 16 in the form of a fistfight. Members of the powerful Arab Rizeigat tribe and the non-Arab Massalit tribe got embroiled in the clashes, which claimed the lives of scores of people, including children and members of the security forces, according to the Sudanese doctors’ union.

A flare-up two days later in South Darfur between the Rizeigat and the non-Arab Falata tribe over the killing of a shepherd caused dozens more deaths and another wave of displacement. The Falata are a cattle- and camel-herding people who trace their roots to the Fulani of western Africa.

FASTFACTS

• UNAMID officially ended operations in Darfur on Dec. 31, 2020.

• Sudan government took over responsibility for protection of civilians in the area.

• UNAMID announced phased withdrawal of 8,000 armed and civilian personnel within six month.

According to the UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, those fleeing the violence into eastern Chad’s Ouaddai province have been forced to seek shelter in remote places that lack basic services or public infrastructure.

In retrospect, warnings by civil society groups, local leaders and experts about the consequences of the UNAMID decision have proved right. Fearing renewed violence, Darfur residents too held protests in late December against the peacekeepers’ departure.

To them, it was not just the lack of experience of the Hamdok government that was a cause for concern. The calm that had prevailed since the arrival of UNAMID was hardly an indicator of the situation on the ground.

While the main conflict has subsided over the years, ethnic and tribal violence still erupts up periodically, mostly involving semi-nomadic Arab pastoralists and settled farmers.

Tribal clashes in Sudan’s Darfur region have killed at least 250 people. (AFP/File)

“The fighting wasn’t quiet as sudden as people thought; there had been some clashes in December for example,” Jonas Horner, senior analyst on Sudan at the International Crisis Group, told Arab News.

“Violence has been actually bubbling up in Darfur quiet consistently for some months, and this really undercuts the premise that security has improved (sufficiently) for UNAMID to leave. I think the auspiciousness of the moment for this violence really has much more to do with the end of the (UNAMID) mandate in Darfur. This matters of course because (the violence erupted) just two weeks after the mission wrapped up, taking into account the drawdown period.”

To be fair, the UN decision to withdraw the peacekeepers from Darfur was taken on the basis of the promises made by the Khartoum authorities. “I think that is also a thing to notice of course: The government didn’t pass its first test at providing security,” Horner said. “This was the period when they were supposed to take over from UNAMID the key responsibility for safety and security of Darfurians.”

The Sudan government’s confidence in its ability to take charge of Darfur’s security may have stemmed from a peace agreement that was signed in October in the capital of South Sudan, Juba, by most of the warring groups, which obliges them to lay down their weapons.

UN decision to withdraw the peacekeepers from Darfur was taken on the basis of the promises made by the Khartoum authorities. (AFP/File)

Two groups have refused to join the peace deal, including the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) faction led by Abdelwahid Nour, which is believed to have considerable support in Darfur.

Although the clashes in West Darfur and South Darfur appear not to involve any of the peace deal’s signatories, a combination of poverty, ethnic strife and violence has left the region awash in weapons and its people divided by rivalries over land and water.

Amani Al-Taweel, a researcher and expert on Sudanese affairs at the Cairo-based Al-Ahram Strategic and Political Studies Center, says the Khartoum authorities failed to deploy security forces in a timely manner to Darfur, despite the region’s history of skirmishes between tribes and ethnic groups with a potential for triggering off wider conflicts.

Amani Al-Taweel says Khartoum authorities failed to deploy security forces in a timely manner to Darfur. (Supplied)

“Darfur’s long-simmering tensions have been compounded by the entry of new groups from West Africa, the lack of a comprehensive resolution, and the absence of the one of the most important militias from the list of the Juba agreement signatories,” Al-Taweel told Arab News. “The combination of all these factors makes the situation in Darfur highly combustible.”

Darfur became synonymous with ethnic cleansing and genocide since conflict erupted in 2003 and left roughly 300,000 people dead and 2.5 million displaced, according to the UN. The recent fighting in El-Geneina was centered around a camp for people who had been displaced by said conflict.

The war had erupted when Darfur’s ethnic minority rebels rose up against dictator Omar Bashir’s Islamist government, which responded by recruiting and arming a notorious Arab-dominated militia known as the Janjaweed.

Since the overthrow of Bashir in April 2019 following large-scale protests against his rule, Sudan has been undergoing a fragile transition. Justice for the people of Darfur was a key rallying cry for civilian groups who backed the removal of Bashir after nearly three decades in power.

The Transitional Military Council that replaced him transferred executive power in Sept. 2019 to a mixed civilian–military Sovereignty Council and a civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok.

Bashir, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court for alleged genocide and war crimes, is currently in custody and on trial in Khartoum. But as the latest outbreak of violence in Darfur shows, the wounds of war will take time to heal.

“On paper, the Juba peace agreement is the main avenue for exit for this kind of violence,” Horner told Arab News, adding that there can be no military solution to a conflict whose roots lie in disputes over sharing of land, water and resources.

“The (Sudanese) government has dispatched a high-level delegation to El-Geneina and its surrounding areas, and that will primarily include the military. This is again a military solution that I don’t think this is a sustainable response to the problem.

Jonas Horner

“There is a need for utilization of local administration leaders, who will be very keen to put the violence back in the box. Admittedly, some recognized militia groups are involved in the latest fighting and they are much less likely to take orders from the local administrations leaders.”

Given the current abundance of goodwill toward Sudan, could foreign countries play a role in defusing the situation in Darfur? “From a security perspective, it is probably too late for the international community to come in,” said Horner.

“The Security Council has wrapped up the UNAMID mandate,” said Horner, adding that the new United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) covers the entire country, not just Darfur.

“UNITAMS is under Chapter 6 mission at the UN level, which means it does not include an armed presence. There are some troops left from UNAMID who are supervising and protecting during the drawdown period, but I don’t anticipate they would be utilized to support in a peace keeping or peace-making venture in El-Geneina or South Darfur.”

Overall, the Hamdok government has won praise for taking bold steps to clear the way for Sudan’s political and economic recovery. The recent removal by the US of Sudan from its State Sponsors of Terrorism List will allow the country to have access to international funds and investment, including the International Monetary Fund.

However, festering problems and disputes of the kind that led to the fresh bloodbath in Darfur have the potential to undo many of the gains made since the ouster of Bashir.

Twitter: @jumanaaltamimi