DUBAI: A former economy minister of Lebanon has coined a word for it: “Libazeula.” Nasser Saidi, who ran the economy at the turn of the century and was also No. 2 in the Banque du Liban, the country’s central bank, says Lebanon faces a scenario that could see it reduced to the chaotic impoverishment of Venezuela, once the richest state in Latin America but now a byword for political, economic and humanitarian failure.

Without urgent action by Lebanon’s discredited ruling elite, and the international financial powers that have the means to resuscitate the country’s economy, the threat is dire.

“Lebanon is on the brink of the abyss of depression, with gross domestic product (GDP) declining by 25 percent this year, growing unemployment, hyperinflation, humanitarian disaster with poverty exceeding half of the population,” Saidi told Arab News.

“Throw in food poverty that could grow to famine conditions, and a continuing meltdown in the banking and financial sectors, and the collapse of the currency, all leading to mass migration. This is the ‘Libazuela’ scenario.”

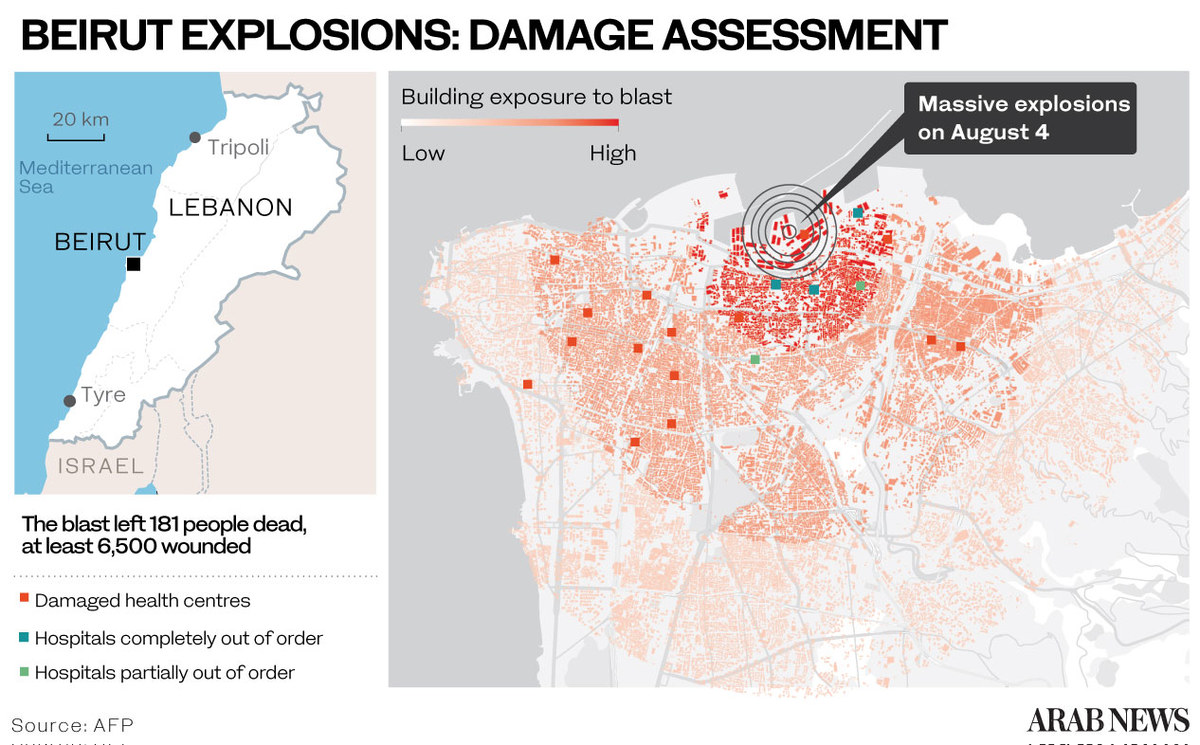

Of all the many crises Lebanon faces in the wake of the explosion that tore the heart out of Beirut on Aug. 4, the economic peril looms as one of the most damaging and intractable.

Without some progress on the economic and financial front, it is difficult to see how there is a future for any Lebanese beyond a small clique of warlords and kleptocrats fighting over increasingly worthless chunks of the economy — a classic failed state by any definition.

Given Lebanon’s geographic location in the heart of a volatile and incendiary Middle East, it is a global challenge as much as a regional issue.

“With Lebanon being the fulcrum of a geopolitical confrontation between the US and Iran, local actors will play strategic games at the expense of an expendable Lebanese population,” Saidi said.

The Beirut explosion has added an extra level of urgency to what was already a desperate attempt to resist economic and financial gravity in the country.

Some estimates have put the immediate requirement — for humanitarian aid at the scene of the blast, through to the cost of rebuilding essential infrastructure in the city — at $15 billion.

But that amount, mind-boggling on its own, pales into insignificance compared to Lebanon’s longer-term financial requirements.

The most recent self-assessment of the country’s financial requirements, by Ghazi Wazni, the finance minister who quit with the rest of the government last week, showed total losses in the banking system at $83 billion, as well as a black hole in the central bank’s accounts of some $50 billion.

Together, those two liabilities amount to more than twice the country’s GDP. To put that in context, it is as if Saudi Arabia was suddenly on the hook for $1.5 trillion.

A youth inspects damage at a local bank branch which was vandalised by protesters earlier, in al-Nour Square in Lebanon's northern port city of Tripoli on June 12, 2020. (AFP/File Photo)

How did Lebanon get into this economic mess? In the wake of the Beirut tragedy, the focus has narrowed to the actions of a relatively small number of Lebanese economic policymakers, power brokers and businessmen who effectively ran the country’s economy for their own benefit for many years.

It has been well documented now that this class of people — in many cases the descendants of the factions that fought Lebanon’s long and destructive civil war in the 1970s and 1980s — operated what would have been known as a “Ponzi scheme” in the corporate world.

Banks, often owned by the same corrupt factions, offered high interest rates to lure in US dollar accounts, which were then lent out to Lebanon’s central bank to keep the whole structure going.

More than half of the Lebanese banking system was denominated in US dollars, and the opportunities for corruption and capital flight were enormous.

Last year, the long-serving central bank governor, Riad Salameh, warned that unscrupulous bankers and businessmen were transferring multimillion amounts of assets abroad as the economic situation deteriorated, even as he imposed capital restrictions on ordinary Lebanese account holders, preventing withdrawals of relatively small amounts.

A woman wearing a face mask against the Covid-19 coronavirus walks past a closed money exchange office in the Lebanese capital Beirut on June 11, 2020. (AFP/File Photo)

“We will do everything in our power to investigate all transfers abroad,” he declared. Just last week, reports alleged that foreign companies linked to Salameh had invested $100 million in assets in real estate in the UK, Germany and Belgium over the past decade.

As the guardian of Lebanon’s financial probity over many years, the case of Salameh was the most notable of many allegations of the country’s economic elite exploiting the situation for their own pecuniary advantage.

In this teetering economic structure, the COVID-19 pandemic exploded like a bomb. As global economic activity ground to a halt in April and May, the Lebanese diaspora worldwide found itself on short-time work or out of work, unable to send remittances back home.

In Lebanon, already-creaking infrastructure simply began to fall apart, resulting in street protests that met with a predictably forceful reaction from security.

Power cuts, water shortages, unemployment, and lack of essential services stoked public outrage against the elites. Then came the Beirut explosion.

Young Lebanese women wearing protective masks and gloves against the coronavirus pandemic, stand on August 5, 2020 amid the rubble in Beirut's Gimmayzeh commercial district which was heavily damaged by the explosion. (AFP/File Photo)

The incredible scenes of death and destruction that day produced widespread and genuine sympathy for the plight of ordinary citizens, and a desire to help with the financial reconstruction that was needed now more than ever.

But it also hardened attitudes in the international economic community toward the corrupt economic system that had allowed the tragedy to happen.

One Lebanese banker based in Dubai, who did not want to be identified, told Arab News: “Of course you want to help people in those horrible circumstances, but do you want to line the pockets of the people whose negligence and criminality caused it?”

Those countries and organizations with the financial firepower to assist were guarded in the aftermath of the tragedy.

A man sweeps glass off the ground along a street outside the local branch of a Lebanese bank after it was vandalised by protesters earlier, in Al-Nour Square in Lebanon's northern port city of Tripoli on June 12, 2020. (AFP/File Photo)

Kristilina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), said: “It is a terrible tragedy, coming at a terrible time. Lebanon has been struggling with profound economic and social challenges, aggravated by a pandemic, but even more so by the shortage of political will to adopt and implement meaningful reforms the people of Lebanon have been calling for.”

French President Emmanuel Macron, during a tour of the Beirut devastation, was even more forthright in his condemnation.

“In a situation like this, it’s perfectly understandable that people hope to get rid of their political leadership,” he said, while committing France to work with others to help with the reconstruction.

Nurses from the Saint George hospital clean one of the damaged rooms, in Beirut's neighbourhood of Ashrafieh on August 13, 2020, more than a week after the massive blast. (AFP/File Photo)

A subsequent fundraiser conference organized by the French got commitments from international organizations for around $11 billion in loans and aid that would go some way to helping with the immediate aftermath of the explosion.

But nobody is in any doubt that this is nowhere near the full requirement for Lebanon to stave off financial and economic catastrophe. “Much appreciated, but multiply by 10 times please,” the Dubai banker said.

The IMF, seen by many as the would-be savior of the country, is sticking to the line it announced earlier in the year, before the pandemic and the Beirut explosion, when Lebanon defaulted on a $1.2 billion bond repayment.

The IMF wants a genuine commitment by Lebanese leaders to reform and economic transparency before it agrees to large bailout packages.

A man clears the rubble inside an apartment in the partially destroyed Beirut neighbourhood of Mar Mikhael on August 13, 2020, more than a week after the massive blast. (AFP/File Photo)

After the mass resignation of the government last week, such commitments seem further away than ever.

Saidi is not optimistic this will come to pass. “The reform scenario requires concerted pressure by the international community, including the imposition of personal penalties and sanctions, on Lebanese bankers and politicians and policymakers for the implementation of reforms,” he said.

“The entrenched kleptocracy, a corrupt political class, banking and financial sector cronies are unwilling to make reforms that would uncover the extent of their corruption, criminal negligence and incompetence. Currently, the Libazuela scenario is more likely.”

-------------------------

Twitter: @frankkanedubai