DUBAI: “Formal + strictly sneakers” — that was the dress code on Tamila Kochkarova’s wedding invitation last year. “I wore a pair of Nike Air Max 98 that were completely white,” the Uzbek photographer and sneaker collector, who has lied in Dubai for the past 16 years, tells Arab News. “My number one priority on my wedding day was my comfort.”

Once considered niche and alternative in the region, sneaker style has now entered the mainstream, and is increasingly popular among women in the Middle East — a demographic that stereotypically splurges on fancy clothing with ornate embellishments, paired with shoes a little more “ladylike” than sneakers.

But while glamour has traditionally been the driving force behind fashion, comfort is now heavily influencing style movements, particularly two of the most popular in this region: modest fashion and sneaker culture. Both have helped shape Kochkarova’s personal style.

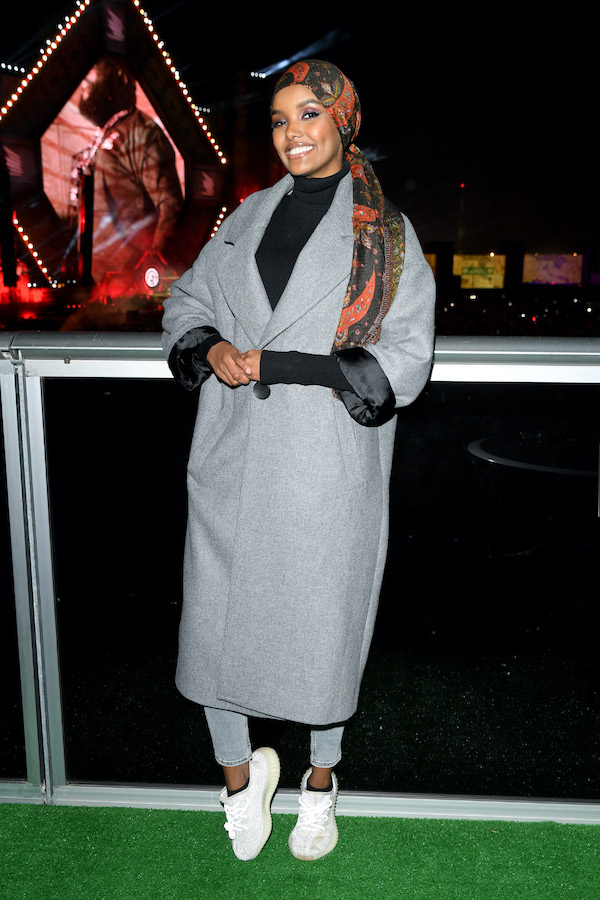

Halima Aden is a US-Somali model. (Getty)

“I got into sneaker culture when I was young, around 12 or 13,” she says. “I just started hanging out weekly in Dubai Festival City at the skate park out there, and my friends were all skateboarders who were really into sneakers.”

Today, skaters aren’t the only ones buying into the trend of clunky, colorful sneakers. Female ‘sneakerheads’ have become influencers on social media, and a number of them happen to dress in skin-covering attire, too. Instagram is now abuzz with modest fashion bloggers — early images of these women were on the more traditionally feminine side — elegant gowns and flowy maxi dresses and skirts, with fabrics fluttering over sling-back heels, strappy stilettos and, occasionally, ballerina flats. But a new wave of sneakerhead hijabis is shedding light on an alternative type of modest fashion.

Su’aad Hassan was born and raised in Dubai and now lives in Canada. (Supplied)

Striking architectural backgrounds, edgy angles, avant-garde poses, and a clear focus on bold — and often rare — sneakers, including limited-edition Nike Air Max, Jordan and Air Force One styles, are features of trending images in the modest-fashion blogosphere. Su’aad Hassan, who was born and raised in Dubai and now lives in Canada, has over 18,000 followers on Instagram. Her outfits include bright tracksuits, plaid blazers, denim vests, bucket hats, silk scarves, retro sunglasses, and a range of sporty footwear. “I think modest fashion and sneaker culture go hand in hand, because, as a whole, modest fashion is a push against the societal standard,” she explains.

Modesty is dominating runways right now, and sneakers are also in vogue, being produced by brands like Gucci, Balenciaga and even Christian Dior, the quintessential “ladylike” French fashion house that recently collaborated with Nike on an exclusive pair of Dior logo-stamped Air Jordans. But both subcultures had been ostracized from mainstream fashion for years. Even in the Middle East, where modest fashion is more prevalent, covering up was not always seen as trendy for young women, Hassan explains.

Sole DXB is the Middle East’s largest sneaker, streetwear and lifestyle fair. (Supplied)

“Whether observing the hijab or not, dressing modestly in the Middle East, especially over the last few years, isn't the cultural norm everyone thinks it is,” she says. “Being able to dress as you wish and to express yourself at your most authentic — choosing yourself and your comfort over anyone’s expectations of you — requires a level of comfort with your identity, and this ties into general comfort in clothing and appearance. Sneakers make this so easy.”

Femininity has long been synonymous with high-heeled shoes. Louboutin — rather than Reebok or Adidas — has been the brand of choice for glamour-loving women, especially in the Middle East. But Athleisure and sports-luxe trends in mainstream fashion have helped popularize streetwear and sporty shoes, and today, women in the region are pairing clunky sneakers with their abayas, floaty maxi dresses and stylish tracksuits — an eclectic mix of sartorial standards, with room for an array of personal styles that may not necessarily conform to tradition.

“Women, especially nowadays in the Arab world, have completely renovated the term ‘femininity’. It’s by our own rules – we can wear a dress with a pair of sneakers and feel very, very feminine. We don’t have to wear six-inch heels to feel like a woman,” says Kochkarova, who is working on launching a website — noboysallowed.ae — dedicated to female sneakerheads from the Arab World. The site, she says, will highlight muses living in the Middle East, or from the Middle East and living abroad, through creative photoshoots and insightful interviews, forming an online community celebrating women and their coveted sneakers.

Joshua Cox is the co-founder of Sole DXB. (Supplied)

Joshua Cox, co-founder of Sole DXB — the Middle East’s largest sneaker, streetwear and lifestyle fair — says that sneaker culture would be “incomplete” without women, and that labels are now paying extra attention to this demographic.

“Our attendance has always been pretty consistent, with women making up half of our audience, but it's only in the last three years that we've seen the brands in the region increase and improve their offering for women,” he says.

Brands are now also working with creatives who identify with both modest fashion and sneaker culture. Reebok, for instance, ahead of Sole DXB 2019, recruited Sharjah-based Sudanese graphic designer Rihab Nubi for its digital campaign promoting pieces from the Reebok by Pyer Moss Collection 3. Nubi wore a top-and-trousers set with a dramatic, pleated, silhouette paired with chunky black, yellow and salmon-toned shoes from the collection, and an off-white headscarf.

Hassan’s outfits include bright tracksuits, plaid blazers, denim vests, bucket hats, silk scarves, retro sunglasses, and a range of sporty footwear. (Supplied)

While religion is certainly a motivator for women who dress modestly in the region, it isn’t the sole reason why women are gravitating towards conservative cuts. Many, inspired by the appeal of covering your body, rather than being pressured to flaunt it, have begun dressing more modestly without even realizing that their attire could be labeled as “modest fashion.”

“It wasn’t that I was dressing to try and be modest, they’re just the type of clothes I happen to be comfortable in. I never really liked to reveal too much,” says Kochkarova of her trademark loose skirts and oversized shirts. She adds that her favorite element of modest fashion is creative and experimental layering: “I’m heavily influenced by fashion in Japan, especially after visiting twice last year, and that’s something that they do on a regular basis.” She also finds inspiration in the up-and-coming sneaker culture in Saudi Arabia. “These kids in Saudi are insanely creative — they’re so underrated,” she says, citing Jawaher of @fashionizmything and Riyadh-based photographer Hayat Osamah as examples.

The ambitions and aesthetics driving the personal styles of these women are unique and diverse, but it’s clear that comfort and practicality are reigning in the modest fashion and sneaker style subcultures, painting a new picture of what an enlightened and empowered woman can look like.

“What we can see as observers…are that women choose to use sneaker culture for self-expression. They aren’t playing to stereotypes on femininity,” says Cox. “By bringing modest fashion and sneaker culture together, they're making it their own, and are contributing to the culture as much as they're taking from it.”