DUBAI: They were told to stay at home and begin remote learning like everyone else. But they had no laptops. How could they participate in their school’s online classes without computers?

This is the kind of dilemma underprivileged families in south Jeddah are facing as Saudi Arabia is compelled to enforce lockdowns on public life to stop the spread of the deadly coronavirus.

The situation is going to be even more challenging with the start of Ramadan, when Muslims are obligated to fast from dawn to sunset.

But help is at hand. Saudi women’s empowerment organizations, both long-time established and recently formed, have risen to the challenge with public-spirited initiatives.

“The families in south Jeddah were the first to be under the 24-hour lockdown in Saudi Arabia because they live closely to each other in a high-risk area,” said Dania Al-Maeena, CEO of Aloula, a Saudi non-profit organization.

“We collaborated with a volunteer group called Khadoum that provides distance learning. Hundreds of individuals across Saudi Arabia supported the campaign, and over 15 companies donated laptops, food and games for the children.”

In one of the campaign’s pictures, a young boy smiles as he holds up the box of his new laptop.

The pain of the COVID-19 pandemic is rippling through almost every segment of society, causing social and economic turbulence in addition to exacting a heavy human toll.

While the virus punishes all, regardless of status, wealth, race and creed, it is almost programmed to hit the weakest and the poorest most.

As in other parts of the world, the pandemic has forced Gulf Cooperation Council member states to throw all their resources at slowing the spread of the virus and take care of the infected.

Before the coronavirus storm hit, these governments were seeking, for a variety of reasons, to boost the share of women in the workforce across both the public and private sectors.

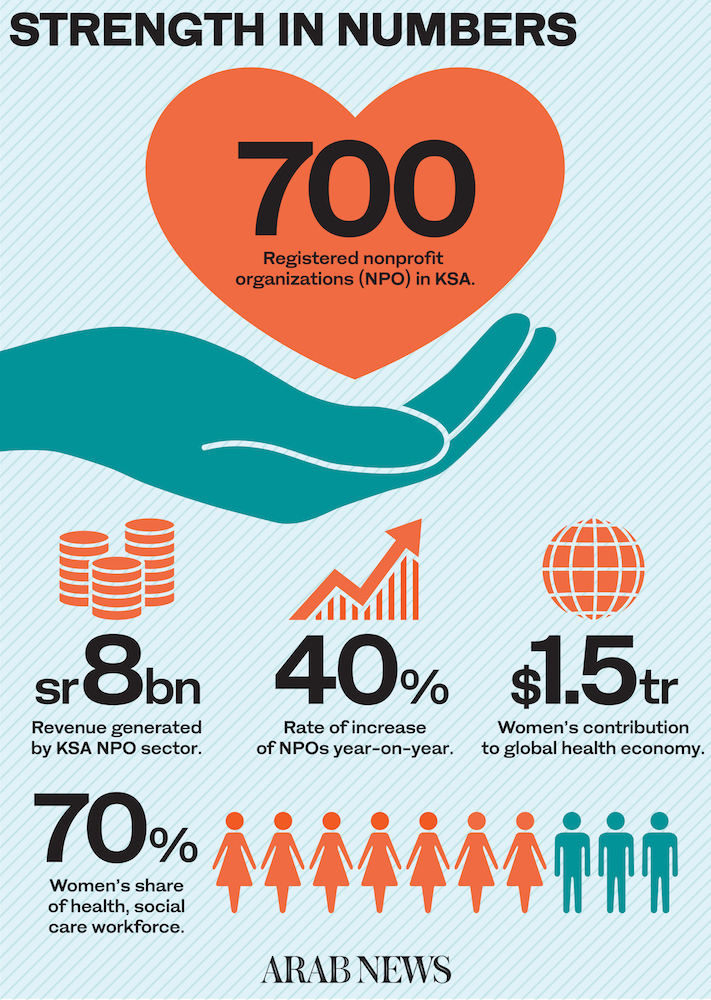

Now, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, 70 percent of global coronavirus frontline workers are women.

“Women are the caregivers, and so women are bearing the brunt of the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Rasha Alturki, CEO of Riyadh-based Alnahda Society for Women, which has provided assistance since 1962 to women who are at risk or belong to socioeconomically disadvantaged households.

Women are still the caregivers, and we have a large role to play at home, in the workplace and in the medical field.

Rasha Alturki, CEO of Riyadh-based Alnahda Society for Women

“While Saudi Arabia’s percentage (of female frontline workers) may be slightly different, we’re still the caregivers and we have a large role to play at home, in the workplace and in the medical field.”

This year, as part of Saudi Arabia’s G20 presidency, Alnahda was entrusted by a royal decree with leading the W20, an official G20 engagement group dedicated to women’s issues.

The W20 started its activities under Saudi leadership in January, and has conducted meetings and interventions throughout this year. These events will culminate in the W20 Summit in Riyadh in October, said Alturki.

At the outset of the COVID-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia, Aloula staged a campaign entitled “Alnass Libaed” (“People Are for Each Other”), said Al-Maeena.

“We placed a new target to help 800 families and 4,000 beneficiaries, providing them with food baskets, including water, dates, canned foods and food donated by restaurants, as well as toys for children,” she told Arab News.

“We also started online courses to teach hygiene techniques to curb the spread of the virus.”

Established in 1962 by a group of women to support families in south Jeddah and registered with the Ministry of Labor and Social Development, Aloula’s founders have banded together for humanitarian work whenever the need arises. The same kind of intervention is visible during the coronavirus pandemic.

The founders of Aloula “had no phones back then. They’d meet and decide how they’d best help the suffering,” said Al-Maeena.

This time, as the Kingdom confronts one of the biggest public-health challenges since its founding, Aloula has managed to help 4,000 people and more than 1,000 families in need.

“Women are by nature caregivers, so this period of upheaval and distress has prompted women in Saudi Arabia to come together more than ever to help those suffering,” said Honayda Serafi, a fashion designer who serves on the board of the Saudi ADHD Society.

She knows the stress being experienced by women all too well, being the owner of an eponymous fashion brand in Lebanon, a country that is facing a trifecta of challenges: A coronavirus outbreak on top of an economic meltdown and political instability since October last year.

Serafi said she is providing meals for 100 families in Lebanon during the coronavirus crisis. “We want to give a sense of hope and positivity during this period to everyone in need,” she told Arab News.

The Saudi ADHD Society, chaired by Princess Nouf bint Mohammed bin Abdullah Al-Saud, has tailored its ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) programs for online platforms in light of the current situation.

A boy holds up his new laptop provided to him by Saudi NPO Aloula. (Supplied)

The organization has created a specialized lecture series focused on different ways young men and women with ADHD can deal with the current situation.

“We’ve provided close to 100 free online counseling sessions,” said Serafi, adding that the society has been receiving many calls for help.

Female staff at Alnahda faced a similar situation during the initial weeks of the lockdowns. “Our social workers were getting calls at 11 p.m. and throughout the night,” said Alturki.

“Women are struggling with marital and sleep problems, legal and rent problems, loss of income, challenges accessing food and water, and home schooling their children.”

Alturki said the socioeconomic impact of the coronavirus crisis cannot be overstated. “Imagine if you had to take care of four children and elderly parents, and also a husband at home who’s out of work,” she added. “It’s a lot of pressure for these women.”

Alturki said all three activities in which Alnahda specializes — grassroots assistance, research and fieldwork, and advocacy — are key to understanding how the situation is affecting women.

In addition, the organization has overseen the distribution of more than 600 laptops among children in need, and connected women in need of masks, sanitizers and financial assistance with charities.

A poster for Aloula’s community-awareness campaign 'Alnass Libaed'. (Supplied)

In Alkhobar, Saudi Arabia, social services of a similar nature are being provided by Fatat Alkhaleej, a charity founded in 1968.

“We’ve sourced and distributed protective baskets among beneficiaries of our programs,” said Ebtisam Abdullah Al-Jubair, CEO of Fatat Alkhaleej. “We’re also transferring SR200 ($53.19) to 173 families as part our orphan-sponsorship program.”

She said Fatat Alkhaleej is handing out food baskets to 1,000 families daily and providing online services.

With the start of Ramadan — a month of fasting, prayer, reflection and community — non-profit organizations and charities usually ramp up their activities across Saudi Arabia.

This year, the fallout from the coronavirus outbreak has posed an unexpected — and unprecedented — challenge to organizations such as Fatat Alkhaleej, Aloula and Alnahda.

But if their track record is any indication, they have proved up to the task, from providing assistance to the elderly and arranging for groceries to be delivered, to lending psychological support.

“While it’s hard to stop the spread of coronavirus, it will happen one day,” Serafi said. “One thing that will never stop is the art of giving, sharing love and support to those in need.”