DUBAI: The Ruqa’a script may have been relegated to history, but its unique characteristics made it a prime choice for decoration and today it is an example of how calligraphic embellishment has produced new modes of artistic interpretation.

As Saudi Arabia celebrates the Year of Arabic Calligraphy, which has now been extended to 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic, we take a look at this vital script and its beginnings.

In the 10th to 13th centuries, a system of proportional calligraphy emerged that distinguished six styles: Naskh, Thuluth, Muhaqqaq, Rayhani, Tawqi’ and Ruqa’a.

This new codification indicated that each letter’s shape was to be determined by a specific number of rhombic dots and their standardized proportions in relation to each other.

Of the six proportional scripts — the “Six Pens” — Ruqa’a to a large extent remains a historical one. According to the team from the Sharjah Calligraphy Museum, it was preferred for chancellery documents or colophons, while institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art propose that it was a script used to embellish books and carpet pages.

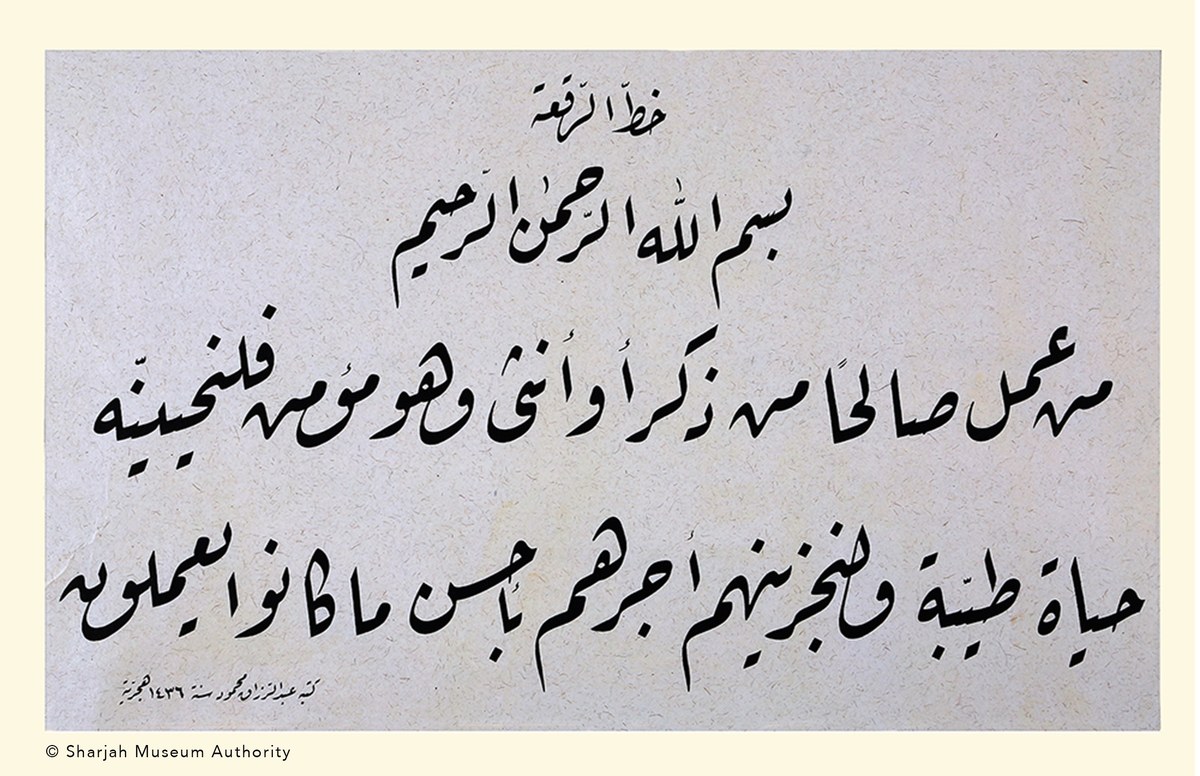

An example of Ruqa'a script. (Supplied)

It is from this initial purpose that it gained its name: Ruqa’a means “patch” or “piece of cloth,” indicative of how it frequently appeared on small papers. Although preferred by calligraphers for more decorative purposes, the historical positioning of Ruqa’a does not mean it is an overlooked or forgotten text, rather, an example of a script which was used for aesthetic purposes.

Derived from Naskh and Thuluth, Ruqa’a was created in the 13th century Hijri by the Ottomans, said the Sharjah Calligraphy Museum, and as per Ibn Al-Nadim’s 10th-century survey of Islamic culture, Al-Fihrist, by Al-Fadl ibn Sahl specifically.

Ruqa’a is characterized by unusual connections of letters that are unlinked in other scripts, such as the dal or alif letters. A smaller version of Tawqi’— the six proportional scripts are often paired with their smaller or larger counterparts — Ruqa’a features accentuated curvilinear strokes and unconventional ligatures, with its descending loops, connected letters and tendency for upward-sloping words at the end of the line shared by some of the other six classical, or proportional, scripts.

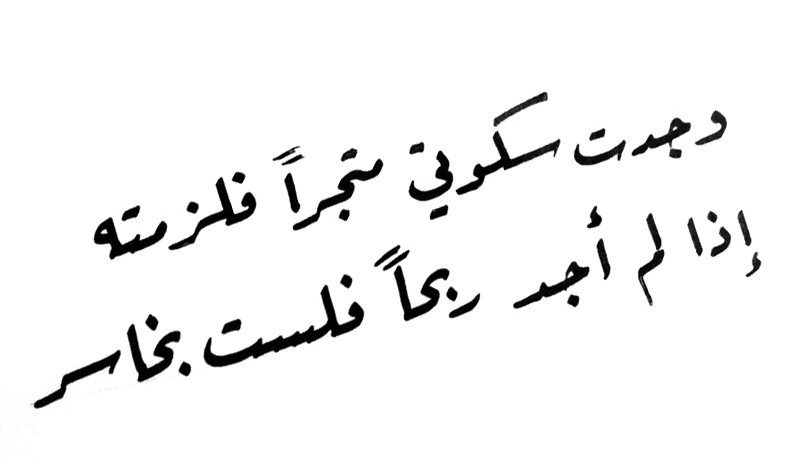

Ruqa’a means “patch” or “piece of cloth,” indicative of how it frequently appeared on small papers. (Shutterstock)

Clipped letters consisting of short, straight lines, simple flourishes and a connection of diacritical dots to isolated letters means the distinct lack of elongations and a need to lift pen from paper made Ruqa’a an efficient, legible script, making it useful for calligraphers for manuscripts, non-religious texts and stories, or private correspondence.

However, despite its fluid execution and fashionable status during the Ottoman Empire, Ruqa’a remained a relatively uncommon script. More often paired alongside others, like the Tawqi’ script, Ruqa’a was eventually relegated to decorative use or reserved for headings. As its purpose was continually refined and its style progressively simplified, most notably by Seyh Hamdullah in the 15th century, Ruqa’a is now rarely found in contemporary contexts.

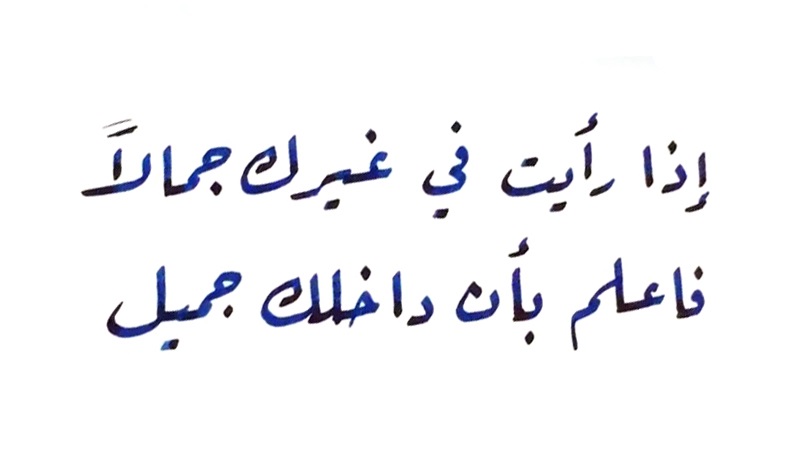

The historical positioning of Ruqa’a does not mean it is an overlooked or forgotten text. (Shutterstock)

But while Ruqa’a as a standalone script fell out of favor, it remains a case study for the constant evolution that all forms of calligraphy have undergone as the standards, needs and artists’ skills have developed since codification in the 10th century.

“Arabic calligraphy is an interesting traditional art where you call yourself a calligrapher if you learned from a master calligrapher, who learned from another master, going back thousands of years,” said French-Tunisian calligraffiti artist eL Seed.

“Calligraphy, from its historical roots, is seen as ancient or old-fashioned, which I find sad, but interest in calligraphy has been given a new wave, a new breath,” he added.

While not a trained calligrapher, the contemporary artist uses a fusion of Arabic calligraphy and graffiti in his own distinctive way to decorate the street, transcribing messages of peace, unity and underlining the commonalities of the human condition.

An example of Ruqa'a script. (Shutterstock)

“I’m trying to be an ambassador for my culture and of Arabic script,” he said. “The fact it’s part of a street art movement makes it a new voice or language for the youth. I’m not a calligrapher and though I can recognize the different styles, I would never be able to do what I’ve done and be doing now if there wasn’t traditional calligraphy.”

While eL Seed represents a new generation showing how dormant styles can be paid homage to while simultaneously revived through refreshed eyes and modified in line with modern necessity, the foundation of calligraphy as artful communication with intent remains.

“When you write with your hand, it’s an expression of your soul,” the artist said. “I feel we’re losing that and it’s important we keep that. I think that’s why people are amazed when they see calligraphy, because it’s a way for people to enter your mind and see who you are on the inside through your way of writing.”