ABU DHABI: On the morning of March 2, a child died after a rickety boat carrying displaced Syrians capsized near the shores of the Greek island of Lesbos in the Aegean Sea.

Within hours, the dead child had become another statistic in the international refugee crisis figures as geopolitical competition between Turkey and Syria, backed by ally Russia, began to hot up.

The death of the unidentified boy came amidst an exponential rise in the number of arrivals on Greece’s shores of displaced Syrians and migrants from other countries headed toward Europe in search of asylum.

Reuters news agency reported, quoting an official source, that during a 24-hour period more than 1,200 migrants, most from Afghanistan and Pakistan, attempted to cross the land border.

Earlier, Suleyman Soylu, Turkey’s interior minister, said on Twitter that more than 100,000 Syrians had left Edirne, a city in northwest Turkey, in the direction of the Greek border.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Greece has said the asylum seekers are being “manipulated as pawns” by Turkey in an attempt to exert diplomatic pressure on the EU.

The EU’s foreign policy chief has warned refugees to “avoid moving to a closed door,” while the bloc has accused Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of using the migrants and refugees his country hosts for political purposes.

Until a ceasefire agreement was reached on March 5 in Moscow between the leaders of Russia and Turkey that appears to be holding so far, most of the casualties of the geopolitical competition were occurring in the northwestern Syrian region of Idlib, where Turkish and Syrian fighter jets were locked in dogfights.

From a purely humanitarian standpoint, Erdogan’s use of the asylum seekers’ desperation as a cudgel to pressure the West, coupled with Greece’s heavy-handed response, would appear to have endangered many more lives besides those of Syrians trapped by the fighting in Idlib.

It all began with an intensified Syrian regime offensive to retake the last opposition holdout and the confirmed deaths of 33 Turkish soldiers in an air attack on Feb. 27.

The Russian defense ministry said the Turkish soldiers were killed in a “bombardment” while operating alongside “terrorists” in the Balyun area where, it said, fighters from the Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham alliance were attacking Syrian government forces.

In response, Erdogan’s government ordered a counter-offensive along its borders with Syria that briefly raised the specter of a direct confrontation between Turkey, a NATO partner, and Russia.

Simultaneously, Erdogan opened Turkey’s western land and sea borders, declaring bluntly “the doors are now open” to migrants and refugees wanting to leave Turkey for Europe.

Hundreds of migrants have attempted to reach Lesbos since. In just two days, March 2 and 3, close to 1,200 people arrived by boat on Lesbos, Chios and Samos, according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

Residents of the three Greek islands staged protests and attempted to block the latest wave of arrivals, according to the locally based humanitarian workers.

Erdogan later ordered the Turkish coastguard to stop migrants from crossing the Aegean Sea, but on the question of allowing them to enter Greece via the land border, he has stayed adamant, inexorably setting the stage for clashes.

With full support from the European Council, both Greece and Bulgaria have sent security reinforcements to their borders with Turkey with the stated aim of preventing people from “illegally entering” their respective countries.

Sentiments have been further inflamed by local and regional media’s depiction of displaced Syrians as migrants who were illegally crossing into the EU. A fire engulfed a refugee shelter near Mitilini, the capital of Lesbos, on March 8 under unclear circumstances, possibly portending more trouble.

CNN said the Turkish state broadcaster TRT had a video showing men allegedly sent back across the Evros River with no clothes by Greek security forces. The river forms the natural border between both countries.

The men said they had been subjected to violence and degrading treatment.

Speaking to CNN, Abdel Aziz, a tailor from Aleppo in Syria, said: “We were caught by military or police, they were carrying weapons ... we were left in our underwear, they started beating us up, some people were beaten so hard they couldn’t walk anymore. They burned the IDs and clothes; they kept the phones and money.”

Denying that the government was using excessive force, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis told CNN that Europe was “not going to be blackmailed by Turkey,” adding that Greece had “every right to protect our borders.”

If the remarks are any guide, attitudes have hardened on all sides since Turkey closed its border with Syria in 2018, leaving many people displaced by the conflict there to camp along the border on the Syrian side in makeshift shelters.

In 2016, the EU and Turkey had agreed on a joint action plan addressing the European migration crisis.

It involved a reciprocal EU-Turkey approach, wherein Turkey would open its labor market to displaced Syrians under temporary protection and Syrian refugees rescued from Greek islands would be resettled, among other initiatives.

For its part, the EU was to offer Turkey economic support and incentives to halt the flow of migrants and refugees into Europe.

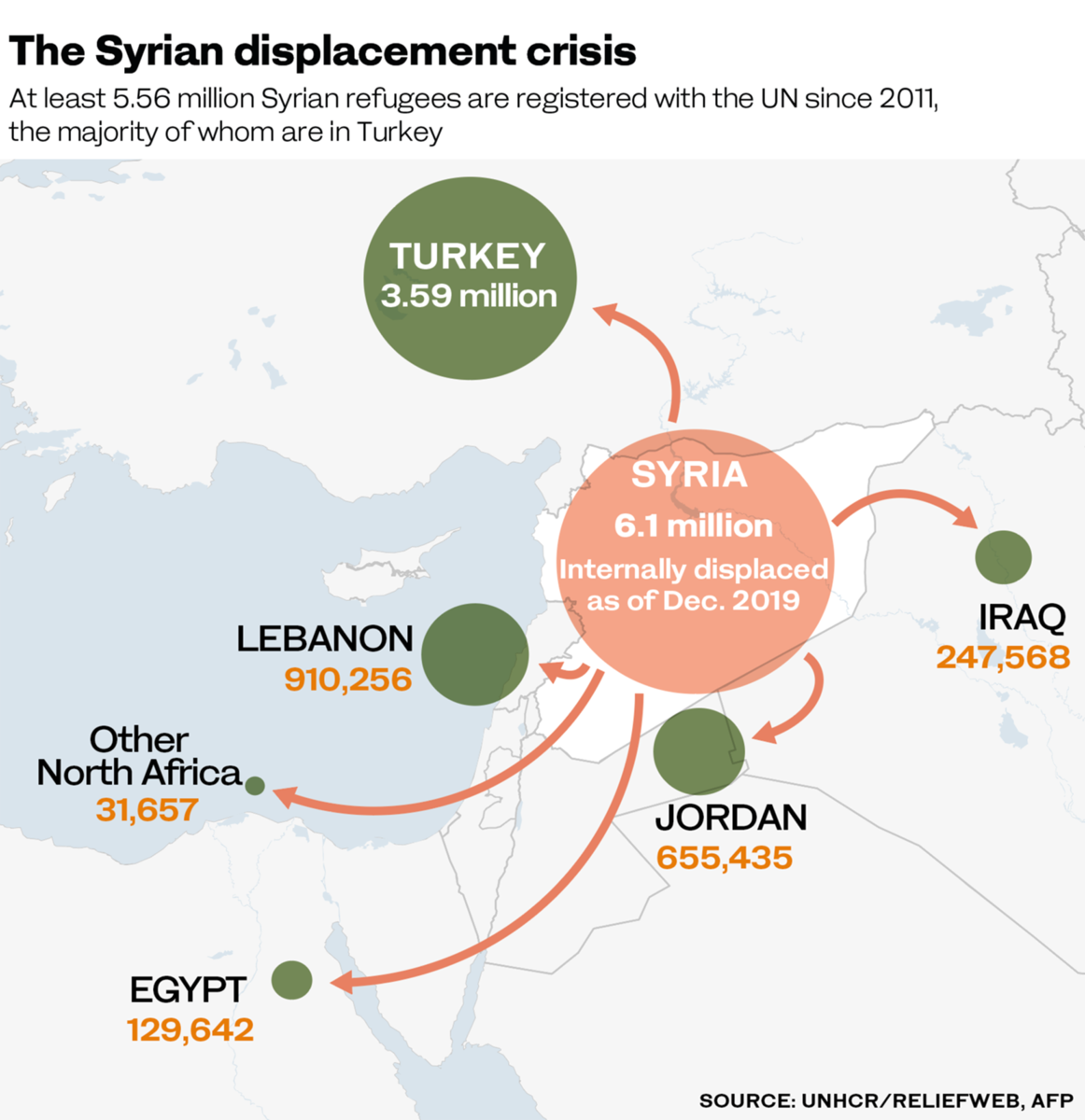

Turkey already hosts about 4 million refugees, including 3.5 million Syrians, but Syrian President Bashar Assad’s military offensive and the subsequent clashes with Turkish forces stationed in Idlib have led to nearly 1 million more fleeing to the south of Turkey’s border.

In effect, intense horse-trading between Turkey and the EU has overshadowed a colossal human tragedy in Idlib — displacement caused by unending conflict and political persecution — and reduced it to a European security problem.

Speaking to the BBC, Ibrahim Abdul Aziz, a Syrian refugee who had been uprooted several times, summed up the dilemma of tens of thousands of his compatriots.

He said: “We moved because of the bombs and came to Darat Izza (town in northern Syria). But then there was more bombing there. Now we don’t know where to go.”

Exploding bombs are not the only worry for Idlib’s populations, a mixture of long-time residents and Syrians evacuated from regions where defeated anti-government groups had surrendered to the regime.

The harsh weather conditions of winter in northern Idlib and Aleppo have compounded the terror and food shortages that residents face on a daily basis. To add to their many worries, there is the risk of a breakdown of the ceasefire.

The deal signed in the Kremlin by Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin establishes a security corridor 6 kilometers to the north and south of the M4, an east-west motorway that, together with the M5, connects the major cities back under the Syrian regime’s control.

Starting from March 15, Turkey and Russia are also due to conduct joint patrols in this area. But unsure of the ceasefire deal’s longevity, Erdogan is threatening to double down on his Greek gamble.

“If the violence toward the people of Idlib does not stop, this number will increase even more,” he said.

“In that case, Turkey will not carry such a migrant burden on its own. The negative effects of this pressure on (Turkey) will be an issue felt by all European countries, especially Greece.”