JAZAN: At the southernmost tip of Saudi Arabia, just a few kilometers from the Saudi-Yemeni border, is the verdant region of Jazan, blessed with its rocky mountain tops, green wadis, deep forests, hot springs and boundless fertile land. It is also home to the local Khawlani coffee bean.

Although the Arabica coffee bean is well known, most people don’t associate it with Saudi Arabia. While the actual origin of coffee is debatable, the ancient tribes of the Khawlan, in reference to their great ancestor Khawlan bin Amir, located between Jazan and Yemen, have practiced the skills and techniques of cultivating Khawlani coffee beans for over 300 years, with the tradition passed down from one generation to the next through non-formal educational methods, including practical training and observation.

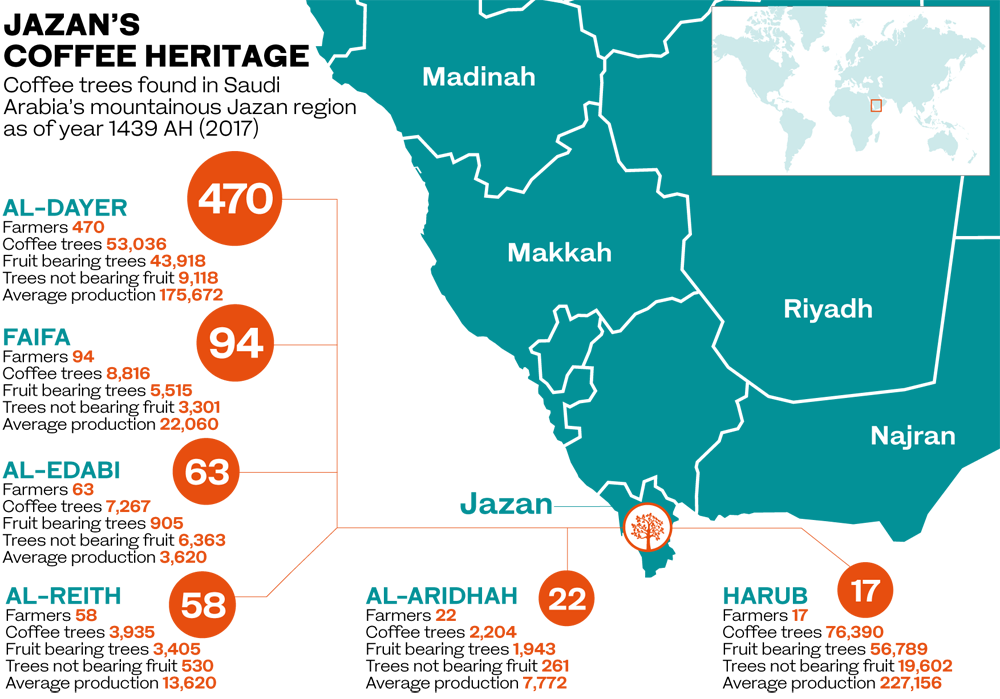

The region of Jazan contains 16 provinces, and six of them practice the cultivation of Khawlani coffee beans. For farmers here, making coffee is a highly respected vocation that gives cultural identity and status to the entire region.

Today, the Saudi Heritage Preservation Society is asking UNESCO to provide protection for the ancient art of Khawlani coffee making. The project, which began in 2019 in collaboration with farmers in Jazan, included documenting the cultivation process of Khawlani coffee beans.

“The number of farmers in Jazan is really high and they face a lot of problems and difficulties, including with water and working resources,” said Rehaf Gassas, project manager at the Saudi Heritage Preservation Society, a nongovernmental organization established in 2010. “Hopefully, by the inscription of this (cultivation process) in UNESCO, it will help promote (Khawlani coffee beans) throughout Saudi Arabia and encourage the nation to help these farmers.”

The bid process itself is time-consuming. It normally takes around 18 months to work on, from field visits to theory work.

On March 31, 2019, the society finished the application and delivered it to UNESCO. By November 2020 they hope to know the decision as to whether they were successful.

“We are very optimistic,” added Gassas. “The community itself is the biggest supporter, because they are very invested in the coffee beans they are planting, and it is really very important to them to show the world that they have this rich culture and heritage.”

Khawlani coffee beans might be one of Saudi Arabia’s best-kept secrets. They are considered one of the finest types of coffee beans in the world, and Saudis are ranked as one of the biggest consumers of the beverage.

In many ways these beans are a national treasure, crucial to the preservation of Saudi heritage and the nation’s cultural identity. “They are described as the green gold of Jazan,” said Gessas. “But there is lack of knowledge amongst Saudis that the Jazan region is one of the biggest producers of coffee in the world.”

In 2017 the Ministry of Interior cited more than 76,390 Khawlani coffee trees farmed by 724 farmers, producing 227,156 kilograms of coffee from an average production of 4 kilograms per tree. “The trees are thought to have been brought from Ethiopia to Yemen, and perhaps from Yemen to the mountains of this governorate,” says deputy governor of Al-Dair, Yahia Mohammed Al-Maliki.

“In the past, people mainly relied on planting coffee beans as one of their major products to make a living during hard times. Nowadays, the situation has changed. People have started to come to the region looking for investments.”

The cultivation process of Khawlani coffee is an arduous one. It involves planting the seeds for the trees, harvesting the fruits that start growing 2-3 years after planting, pruning the trees, collecting the fruits and transferring them to the rooftops of houses to put on dehydration beds in a cool shaded area to dry.

There the fruits must be stirred by hand until they turn black. They are then peeled, roasted and ground. The picking itself involves attention and care. The red color indicates that the fruit is ready for picking, which needs to be done using a twisting method to ensure the branch is not damaged in the process in order to ensure it can bear fruit next season.

“We hold the fruit and with a little twist, we pick it off the tree,” said Hussein Al-Maliki, owner of Mefraz, a local coffee brand that recently won a coffee roasting competition in the UAE, and which hopes to soon distribute internationally outside the Kingdom.

The significance of Khawlani coffee goes beyond its cultivation. The process entails a celebration of familial ties and heritage as well as respect for the local land. Mohammed Salman, a 70-year-old farmer in Al-Dair, has been cultivating coffee beans since he was born. “I have learned the process of planting coffee from my father, who had inherited it from his ancestors,” he said. “He gets up each morning, performs his prayers, has his breakfast and then goes out to his farm.

“I stay at the farm irrigating my trees, cleaning the soil, helping the two workers I have here until the sun sets and then get back home,” he continued. On the weekends, Salman’s two sons join him and the cultivation becomes a family activity. “I teach them how to care for our coffee trees and even how to pick the fruits that are ripe,” he added.

At the core of Khawlani coffee is the beauty of generosity. Offering small cups of coffee to guests is an age-old tradition in Saudi Arabia — one practiced since ancient times. For the community of Khawlan, it is of utmost importance to offer visitors coffee using beans harvested from their farms. It’s a sign of honor and respect. Now, on the verge of UNESCO protection, the Khawlani farmers will soon offer their golden cups to the world.