DUBAI: Big tech companies such as Facebook and Google are not doing enough to counter hate rhetoric and terrorism and need to “man up,” MBC Group TV director Ali Jaber said on the second day of Dubai’s Arab Media Forum on Thursday.

“Digital platforms have become platforms that spread bigotry and hatred. They have to man up and organize and be more transparent,” Jaber told Arab News, adding that “they need to be a force of positive change, and not the negative force they have been for the past few years.”

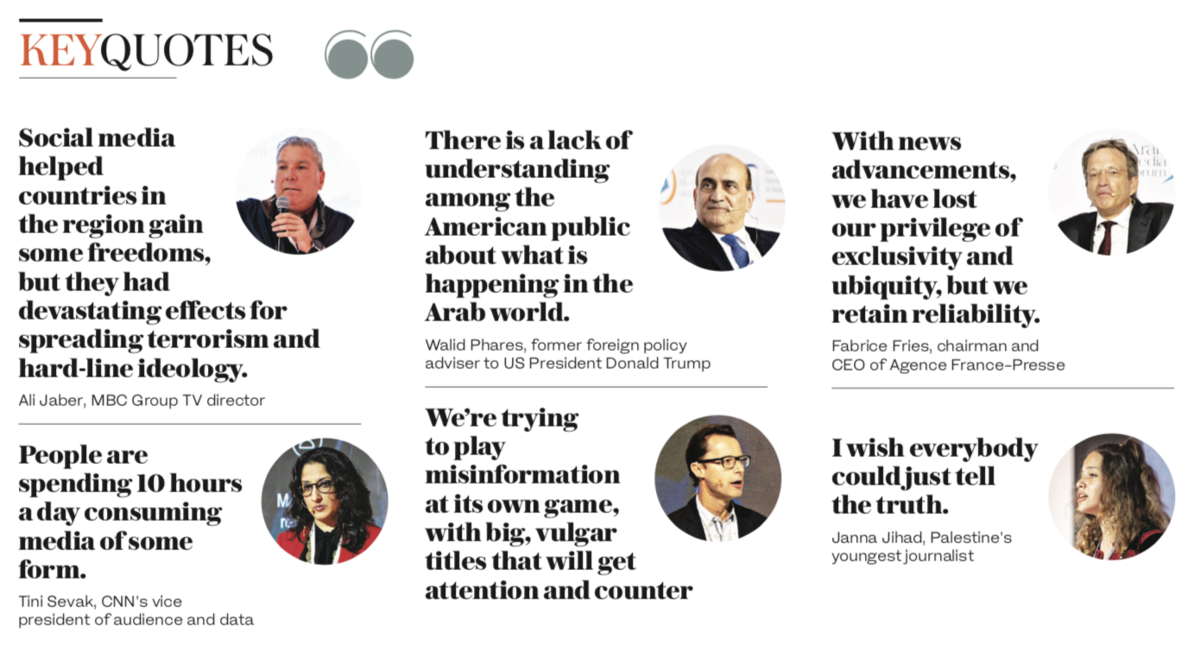

At a session titled “What Type of Media Do We Want?” Jaber told a fully-packed hall at the Dubai World Trade Center that “social media helped countries in the region gain some freedoms, but they had devastating effects for spreading terrorism and hard-line ideology.

“I have invested in the forum for the first time to launch a global anti-extremist initiative in the region,” he said, adding that “it is the responsibility of every journalist and media entity to counter and tackle these rhetorics. Whoever spreads them is not a journalist, but an instigator.”

Jaber also spoke of social media and big tech companies’ presence in everyone’s lives, for example, how Google knows “when and what we eat, where we go, what we watch and what we do.”

“Google has an effect on us that we cannot even imagine, we don’t live in the world … we live in the Google world,” he said.

Countering terrorism and hate rhetoric in the region’s media has been a prevalent theme throughout the two-day forum, with several sessions highlighting the need to act swiftly and vigilantly.

Media agencies have been stepping up in terms of countering the spread of such deceit through the news mediums. Arab News recently launched a new series called Preachers of Hate, in which the words of the instigators are being documented and analyzed in an effort to inform the public of their ubiquity in all religions, and to create a dialogue to act against their destructive influence.

“The media possesses the power of the word and utilizes this power to make a positive impact on the community. Good words will grow and prosper. The media must maintain high levels of integrity and professionalism,” Dubai Ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al-Maktoum said at the forum on Wednesday.

Alongside countering terrorism and hate, delegates spoke about the continuing battle against fake news and misinformation. “We’re trying to play misinformation at its own game, with big, vulgar titles that will get attention and counter false news, as well as show and explain our craft of true reporting and fact-checking in Arabic and English,” Phil Chetwynd, the global news editor at Agence France-Presse, told the audience in a session titled “Standing Together Against Fake News.”

“We are in a position at the moment where we must justify everything that we are doing,” Chetwynd said.

He showed examples of groups on Facebook getting more readers of stories than news entities do, which is troubling given the amount of misinformation that could be spread via these mediums when left unchecked.

Much is being done in countering fake news dissemination online. Several workshops and software programs were presented to journalists to help verify and fact-check certain news articles and images that are found online.

Daniel Funke, a journalist working with Poynter, a US school for journalists, gave a talk on “The Age of Fabrications,” in which he explained different types of misinformation and how it spreads.

“It’s not that hard to find fake news, but it’s really hard to tell when you want to intervene because you don’t want to amplify false narratives,” he told Arab News.

“Misinformation is trying to get a reaction out of you, so the headline could be all caps, big red letters, salacious claims, exclamation points, heavy punctuation … any of those things immediately should be a sign that things are probably not true,” he said.

But fake news could still appear in less obvious ways as it continuously adapts to draw in more viewers. “You see a lot of misinformation in your news feeds, and fact-checking journalists have become a primary defense against fakery. Anyone can become a fact-checker,” he said, adding that “if your mother tells you she loves you, check that out … check everything.”

Other sessions in the forum tackled the industry’s relationship with the political sphere. “There is a crisis between media and politics in the modern world,” said political analyst and author Abdel Monem Said. “Many media figures have become politicians and vice versa, and this is similar to the impersonation of roles between the political and media fields.”

He was speaking alongside Abdulrahman Al-Rashed, head of the editorial board at Al Arabiya, and Walid Phares, US President Donald Trump’s former foreign policy adviser.

“For us in the media, we try to give all parties space for self-expression, and this is the job of newsroom workers,” Al-Rashed said, adding that media should be unbiased and give a chance for all to voice their opinions and concerns.

Phares, however, gave the audience an insight into the West’s views of the Arab world, specifically those of US citizens. “There is a lack of understanding among the American public about what’s happening in the Arab world,’ he said.

The forum’s other sessions included one on the future of print journalism. “Print is not dead,” said Nayla Tueni, the editor-in-chief of Annahar newspaper in Lebanon.

Tueni referred to the day that Annahar printed blank pages in protest at the recent political stalemate in Lebanon, in which it took six months to form a government.

“Everyone went and bought the paper, which was only white (pages),” she said. “Print is still relevant.”