Dubai: “I live the Nakba every day and everywhere I go,” Dr. Mohammed Hajjaj, a 71-year-old Palestinian doctor whose family was forced to leave Palestine during the 1948 mass exodus ,told Arab News over a crackly phone line from his home in Amman.

Dr. Hajjaj was just four months old when Israel declared its independence 70 years ago. More than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs were forced to flee the lands they inherited, the businesses they built, and the homes they had grown up in — an event that became known as the Nakba.

“I see that what happened with the Palestinian people, didn’t happen to anyone else,” the doctor said.

“I know that so many peoples were colonized, but the colonial power came and the people stayed there. For the Israelis, for the Jews, they displaced the Palestinians, they sent them out of their land, they killed people, they made so many massacres in Palestine.”

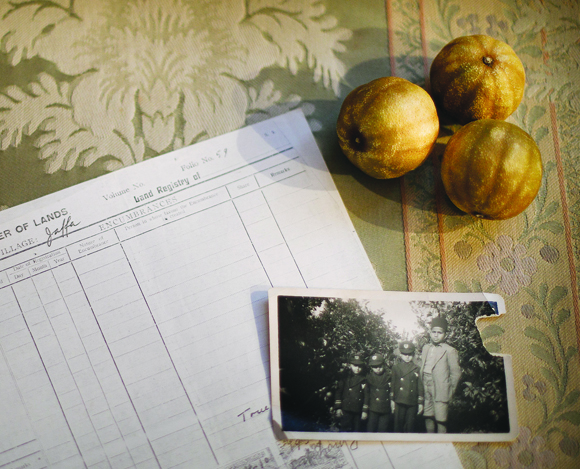

Dr. Mohammed Hajjaj’s keepsakes of his birthplace include shrivelled oranges, a memento of his parents’ farm in Jaffa, which they fled in 1948. Annie Sakkab

The son of orange exporters, Mohammed’s journey started when his parents had to leave Jaffa, the second largest city in occupied Palestine. His mother took him to Lebanon with her family for six months while his father and grandmother went to Amman ito find work.

Having been an infant at the time of their flight, Mohammed grew up in the aftermath of Nakba and the consequences that followed.

“The first thing I recall was that life was a tent for some time and then they built very simple houses – everything was difficult at that time. People lost all their resources, jobs were scarce. Jordan also was poor in resources,” he said, adding: “I remember I lived a very, very difficult infancy and childhood.”

Mohammed grew up surrounded by tents, with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency providing classes, care in medical clinics and aid. For a few years, they lived in camps made up from thin white or blue tarpaulins, which were just supported by a few pillars.

Mohammed grew up surrounded by tents, with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency providing classes, care in medical clinics and aid. For a few years, they lived in camps made up from thin white or blue tarpaulins, which were just supported by a few pillars.

Coming from a very simple background, Mohammed went on to work and study hard to come out fifth in the country in his secondary school government examinations, before receiving a scholarship to Cairo University, where he studied medicine.

“In my childhood we didn’t have electricity,” he recalled.

“I used to study at night on the kerosene lights and wake up early in the morning to study in the daylight.”

Having been born in Palestine, raised in Jordan and educated in Egypt, Dr. Hajjaj refers to himself as an “Arabic citizen” rather than from a specific place.

“I was raised when we used to say that we are one nation from the Arabian Gulf to the Atlantic Ocean, so I believe we are all from one nation.”